Tony Bennett, MTV Star

There’s a moment relatively early in Tony Bennett’s first MTV Unplugged set, filmed in 1994, when he starts poking some fun at the fact that he’s recording an Unplugged set. “You know, this is so terrific, being unplugged,” he says, the audience chuckling. “I really like it.”

The joke, of course, is that Bennett is already an acoustic performer, surrounded by other already-acoustic performers—in this case, the Ralph Sharon trio. (Unplugged, for those who might not be familiar, is where MTV-adjacent musicians perform an unamplified set for a relatively intimate audience.) On top of that, Bennett spent years performing for people—at home while his family gathered in a circle around him as a child, at the opening of the Triborough Bridge as a slightly older child, as a singing waiter in New York City as a teenager—before he first got to do so using a microphone. In other words, it’s not like the technology was ever the point.

“Let’s really get unplugged, okay?” Bennett continues. He then launches into a beautiful (and mic-less, save for the ones needed to record the episode) rendition of “Fly Me to the Moon,” the song most associated with his late hero and close friend, Frank Sinatra. He sings the song higher than you might be expecting if you’re used to Sinatra’s version or even Bennett’s more recent work; what comes through above all else is his barely-contained pleasure singing it. The episode was the second to air in Unplugged’s fifth season—just after Stone Temple Pilots, a few before Lenny Kravitz. Bennett was 67 at the time.

I officially committed to writing this piece last summer. It was supposed to go out in September ahead of Tony Bennett and Lady Gaga’s Love for Sale (2021), but by the end of that month I’d gotten myself too worked up about it and failed. I then could not work myself back down enough to finish it through the remainder of the fall… and a sizeable chunk of the winter, which is why you’re reading it in February.

To back up about a decade or so, I first learned who Tony Bennett was shortly after I turned 14. He was 83, and therefore the oldest artist to participate in “We Are the World 25 for Haiti” (2010), a song I was weirdly obsessed with upon its release. (While I obviously double-checked to confirm this, I knew without really needing to that he’s the voice behind “That someone somehow must soon make a change” in the second verse.) When I showed the video for the song to my dad in 2010, he alerted me to Bennett’s existence by exclaiming his name in the middle of it.

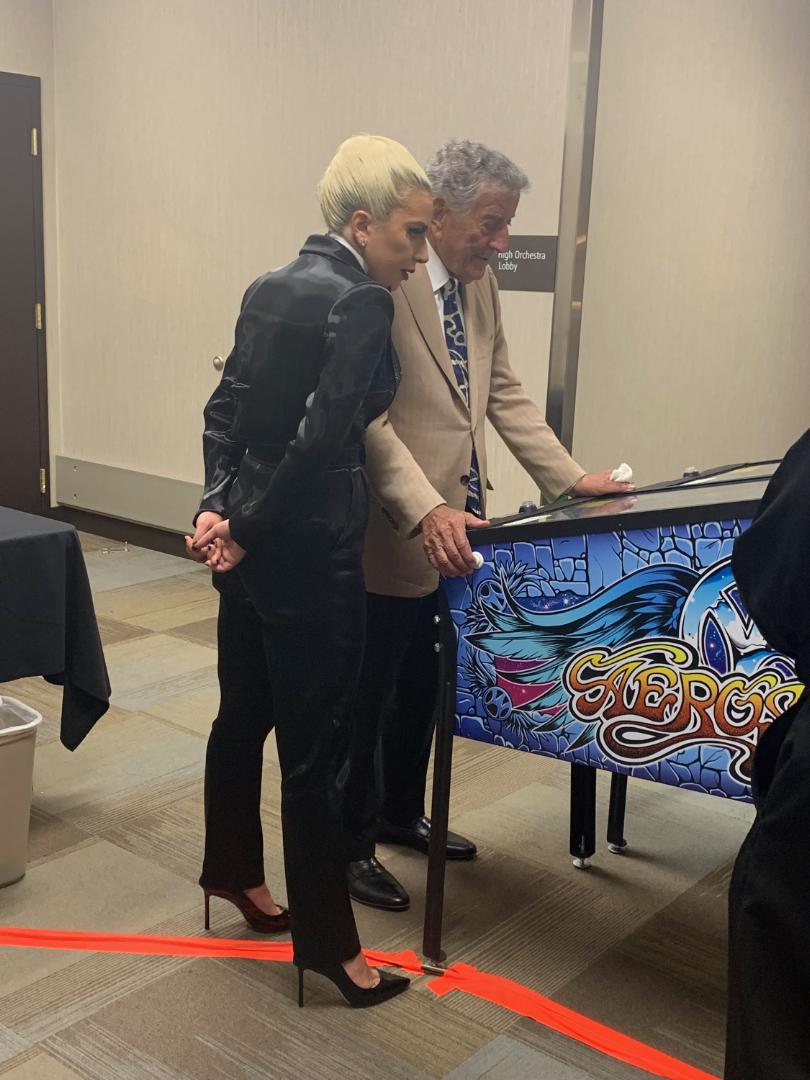

But I’d also by that point become something of a Little Monster, which meant that I’d never escape Bennett again starting the next year, when Gaga joined him for “The Lady Is a Tramp” on his Duets II (2011) album. (That kicked off a so far decade-long friendship, the subject of the forthcoming documentary The Lady and the Legend.) The video for their duet was a massive help to me in endearing Miss Germanotta—a still new-ish and often perplexing public figure, and someone I didn’t shut up about all through high school—to my parents. It also allowed the stars’ first album-length collaboration, Cheek to Cheek (2014), to become a staple at my family dinners, especially around the holidays. Separate to Gaga, Bennett would pop up here and there throughout my teens in relation to another collaborator, Amy Winehouse: giving a tribute to her at the 2011 MTV Video Music Awards (VMAs) shortly after she died, and playing a small but significant role in the documentary Amy (2015).

During this same period, while Bennett came to have a sort of pleasant omnipresence in my pop culture diet—but always through some other artist—I knew virtually nothing about his personal life or background, or really his solo career. That only started to change in February of 2021, when, in an exclusive AARP The Magazine report, it was revealed that the now 95-year-old was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s back in 2016. Of all the channels to release this news, AARP (aka the American Association of Retired Persons) seems to have been strategic on the part of Bennett’s family. The piece, written by John Colapinto, is at once a condensed biography of the star, an announcement regarding new work with Gaga, and an Alzheimer’s explainer. Put differently, the story’s celebrity news potential, especially in light of the Little Monsters whose clicks were practically guaranteed, ensured that thousands of readers of all ages would have to learn something about the disease—what it is (the most common form of dementia), how it typically progresses, and how it might be prevented.

Having then not yet read the piece, I went to fill my fiancé in on the gist of the news and surprised us both by breaking into a sob before I’d gotten through the headline. Neither of us knew why I was so upset. It may have been that I’d never before really thought about the whole ‘pleasant omnipresence’ thing; it may have been the nature of the disease itself, which has always bothered me; it may have been something akin to regret over not knowing anything about this living legend and feeling like I’d fucked up. I then read the piece, and indeed felt silly about having never looked into his life story previously. Aside from being a music great, Tony Bennett is a veteran, an activist, a philanthropist, and an accomplished painter, someone who has generally speaking seen and done A Lot. In many ways, he also embodies the promise of the so-called American Dream, a child of immigrants who hustled (a word I virtually never use unironically, so enjoy it) his way out of poverty and into history.

But there was a detail that stood out to me in particular in Colapinto’s account of Bennett’s life. “Ten minutes into my visit, Tony’s oldest son, Danny, joined us in the studio,” he writes. “He was crucial to the mid-1990s career rebirth that made Tony (then in his late 60s) an unlikely staple of MTV.” I was born in 1996, and not into an especially jazz-inclined household—again, I’d never really been given a reason to catch up on Tony Bennett—so while this will be old news for a lot of people reading this, it wasn’t at all for me. And, learning of it prompted what’s officially become a year-long journey of immersing myself in his life and work, one driven as much by that sense of shame I described earlier as my desire to fill this gap in my MTV-related knowledge. I hadn’t realized that the art I’d spent a decade or so enjoying was actually just the latest chapter in a story that began decades ago—and which originated, at least to some extent, as a strategy to revive Bennett’s career after one of the lowest points in his life.

So, for the rest of this instalment, I’d like to tell that story. I’ve geared it towards the reader like me for whom it’s relatively novel—Bennett’s MTV-facilitated revival doesn't seem to be common knowledge among people under 30 or so, however pop culture-obsessed—but I’ve tried to make sure that you’ll get something new out of it even if, say, you caught his Unplugged set as it first aired. Though I originally intended to focus only on the ‘80s to present, I’ve ended up writing more of a crash course in his life and career, with an eye towards some of the people, places, and things you’re more used to reading about in this newsletter. If I do my job correctly, you’ll agree that the first chunk of his life was far too fascinating to set aside anyway, and I think that including it ultimately does better justice to the stakes and sheer accomplishment of these last four decades.

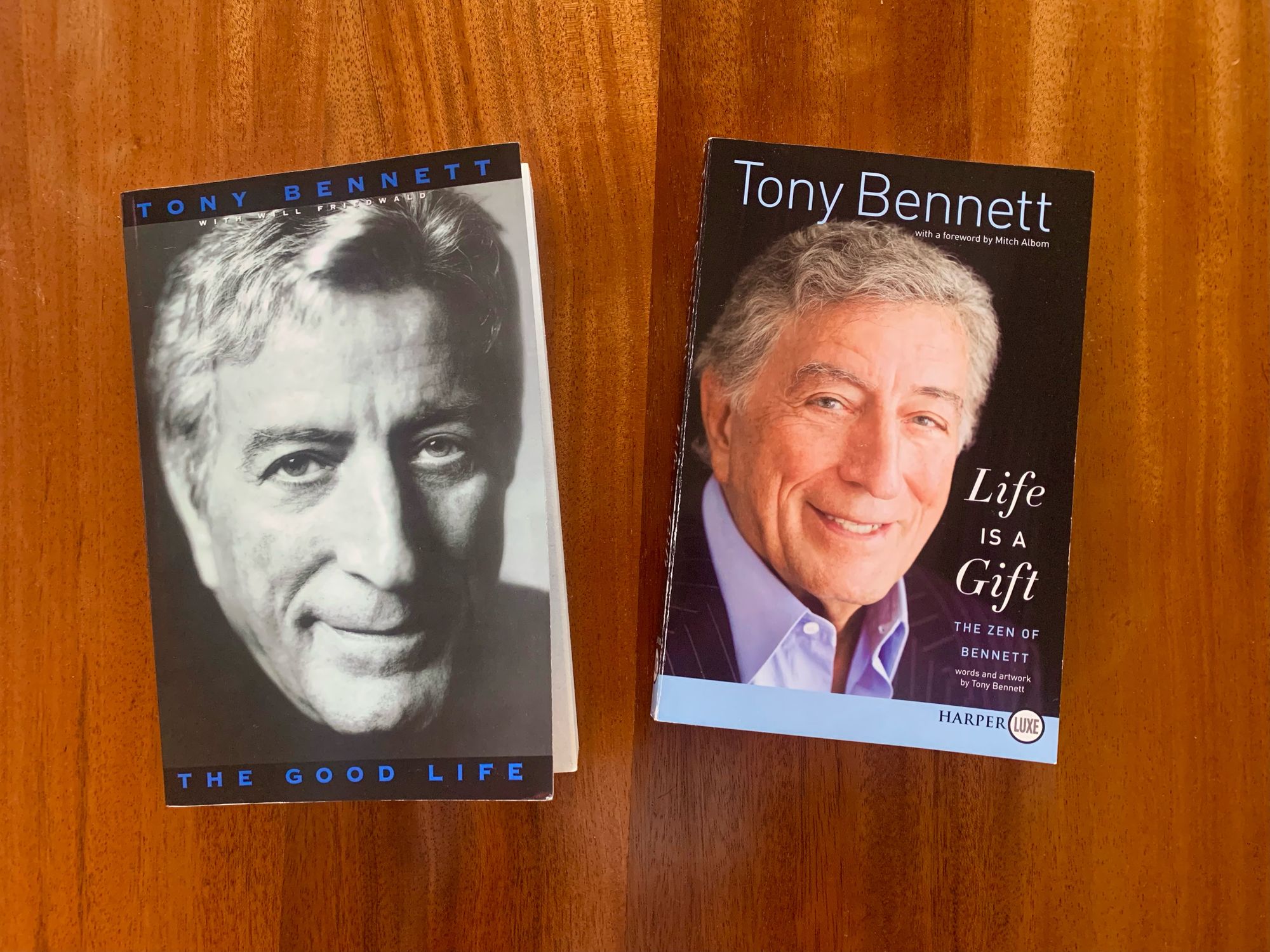

Research-wise, my starting point was Bennett’s autobiography, The Good Life (1998)—the only traditional memoir he’s written (with author and critic Will Friedwald), though he’s also published numerous books on more specific topics (his painting, his loved ones, and so on). I opted to read just one of these in full, Life Is a Gift: The Zen of Bennett (2012), which sees him lay out his personal and artistic philosophies.

While The Good Life, published when Bennett was in his early 70s, is an autobiography for all intents and purposes, it doubles as a crash course in jazz (one I sorely needed, and which has shaken up my music taste in unexpected and ongoing ways), triples as an overview of television as a medium, and—by default of the years the star has been alive—quadruples as a sweeping account of the 20th century, or at least three quarters of it. Over the course of the book, he’s drafted into the Second World War, interviewed by a young reporter named Jacqueline Bouvier, helped through “a case of the butterflies” by a cigar-smoking Orson Welles, animated for an episode of The Simpsons, and accompanied on a private jet by a postpartum Madonna. (Unless I specify a different source below, assume that I’m quoting from The Good Life.)

Then, there was the music: I’ve listened to 65 Tony Bennett albums as of this writing, which I know because I track that sort of thing. I also watched five films and television specials: the documentary Duets II (2012), where he and his duet partners record his album of the same name; The Zen of Bennett (2012), another film produced around the same time (and a companion to the Life Is a Gift book); his first Unplugged episode, the one I used as my opener; One Last Time: An Evening with Tony Bennett and Lady Gaga (2021), filmed last August and released in November; and a more recent Unplugged episode, filmed with Gaga last July and released in December. There were several other things I would have liked to see, but I think that I needed to cut myself off at a certain point.

This is the kind of project I haven’t embarked on in a couple of years, not since one of the first things I ever wrote about Madonna, but I’ve also never embarked on a project of this scale; Bennett has been a recording artist for more than seven decades, which is a lot of material to go through. (I spent altogether less time researching and writing my master’s thesis.) It gave me something to do in the background of 2021 and this first bit of 2022, and has ultimately been a great way for me to process what I guess amounts to my own grief regarding his condition. Not long after I started it, and presumably because I’d been tweeting about him a lot, I was invited to write a pre-obituary for him by a publication I’d wanted to work with forever (and still do). (Pre-obits are a common media practice for public figures of his age—however morbid they might sound at first—as they help publications ensure thoughtfulness and accuracy in their coverage for whenever said public figures do pass away.)

I ended up turning the opportunity down; I was too early in my research, but I also wanted to be able to move forward with my music video angle, and to not feel limited in terms of length or turnaround or scope. This is by far my longest newsletter instalment yet, though I promise that it’s been reined in to the best of my ability—I’ve cut hundreds and hundreds of words out of it—in keeping with multiple lessons from Life Is a Gift, not least: “It’s very important to know what to leave out, thereby emphasizing what remains.”

So with that, here’s the story of Tony Bennett, MTV star.

Anthony Dominick Benedetto was born in Queens, New York on August 3, 1926, more or less into the Great Depression. His mother, Anna (née Suraci), had been the first in his extended family to be born in the United States, the Benedettos and the Suracis originally hailing from a small village in Southern Italy—so small, actually, that Bennett’s parents were first cousins. Put differently: his grandmothers were sisters, but he stresses that this wasn’t so unusual in context.

Tony, the third and youngest child in his family, was the first to be born in a hospital. He was a silly and sometimes reckless kid, at one point nearly burning down the Benedettos’ Astoria home, and—get this—hit by three different cars during his childhood. “I had a habit of walking backward down the street,” he writes. “Don’t ask me why.” He spent his younger years goofing around with his older brother, John Jr., who studied opera and regularly performed at the Met with the children’s chorus. The patriarch of the family, John Sr., had raised his children to appreciate the arts, often reading them classic literature and taking them to see movies. (Mary, the oldest of the three children, would later work for Tony once he became a recording artist.) Tony could sing himself, but “to compete somehow for all that attention” he emerged as the family comedian, impersonating radio personalities and otherwise trying to squeeze laughs out of everyone. He also showed a lot of promise when it came to visual arts, the sort of kid whose chalk drawings on the sidewalk were a little too good.

Anna was a seamstress who frequently brought work home to do for the evening. John Sr. was a grocer but often too ill to work; doctors guessed that his heart was weak from having had rheumatic fever as a child. John Sr.’s health slowly declined over the course of Tony’s childhood, and he eventually died when Tony was a preteen, leaving Anna responsible for the trio of kids. One of Tony’s worst memories is being in the room when his mother got her finger caught in the needle of her sewing machine. He vowed that he’d one day do well enough for himself that she could retire. For a while, he attended the recently-founded School of Industrial Art in Manhattan (now the High School of Art and Design), but was ultimately forced to drop out to help Anna make ends meet (“one of the biggest regrets of my life”). He was a terrible elevator operator and an indifferent paperboy; singing was substantially more enjoyable. So, he sang for money whenever possible, working as a singing waiter and entering himself in amateur nights around town. He called himself “Joe Bari,” his given name having been deemed “too long” and “too ethnic.”

In late 1944, three months after he turned 18, Bennett received his draft notice. Nothing about being a GI seems to have been glamorous to him, or even all that glorious; he summarizes the whole experience as “a big, tragic joke.” (He’s been a self-described pacifist ever since, repeating that war is “the lowest form of human behaviour” anytime he's asked about it.) As early as basic training, he “began to have a really hard time with the whole military philosophy,” finding the environment dehumanizing and abusive. Not too long after New Year’s in 1945, he was shipped out as an infantryman, marching with his colleagues from France to Germany to replenish the front line. (One of his war buddies was Arthur Penn, who’d later direct things like Bonnie and Clyde [1967].) “The winter nights were brutally cold, and sometimes they would last sixteen hours,” Bennett remembers. “Sixteen hours of lying underground in a foxhole, alone, watching and listening for the enemy.” He often sketched things to distract himself.

Life ‘on the line’ entailed many blood-curdling brushes with death—a curious theme in Bennett’s life more generally—but he actually devotes more of the chapter in question to what he calls the “bigotry” of the American army. Though exceptions were always made for the Italians, anyone who wasn’t white and Christian got picked on; at one point, he was demoted from corporal to private—his badge literally razored off of his uniform and spit on by a lieutenant—for fraternizing with a Black friend he’d run into from high school. For Bennett, the only redeeming experience of the war itself was the day that he was among the soldiers pulled off the line to see Bob Hope perform: “At that moment he made me realize that the greatest gift you can give anybody is a laugh or a song.”

Since he didn’t arrive in Europe until pretty late in the game, he hadn’t been overseas long when he found himself, at 18, helping to liberate a sub-camp of Dachau, about 30 miles from the main camp. The experience comes up in both of the books I read, but he spends maybe a combined page on it, seemingly not all that interested in rehashing what he saw. He offers only in The Good Life that—“to [his regiment’s] horror”—half of the camp’s remaining population had been killed the day before his arrival.

After V-E Day, soldiers got to go home on a sort of points system; again because Bennett hadn’t been shipped out until the last stretch of the war, he wouldn’t get back to New York until almost a year and a half later in August of 1946. In the interim, he cut his teeth performing in the realest sense yet with the 314th Army Special Services Band, which did regular live broadcasts from the opera house in Wiesbaden, Germany. He remembers this as an incubator-like period that brought enormous creative freedom; the band could perform anything they wanted so long as they could arrange it, and would jam together to fill the time between performances. “This was the first time I ever smoked pot,” he adds. “But after what we’d been through, we felt that anything that would help us forget was worth looking into.” It was also with the Special Services Band that he made his first record, “St. James Infirmary Blues.” In the late aughts, a friend of his located and gifted him an original copy, which was then released to the public.

The experience solidified Bennett’s desire to make it as a singer, but once he got back home, he spent years struggling to find steady work. To abridge this time: he did a stint at the American Theatre Wing studying bel canto singing, an opportunity made available to him as a veteran; he badgered club owners and booking agents, auditioning for anything and everything—including the chorus of a Broadway show, but no dice. Things started to pick up when he met his first manager, Ray Muscarella, and in 1950 he was signed to Columbia Records on the impressiveness of a demo of “Boulevard of Broken Dreams.” (Columbia had also recently scooped up his good friend, Rosemary Clooney, still relatively unknown the way he was.) By that point, Bennett had managed to make some famous friends like the legendary Pearl Bailey and even Bob Hope, the latter suggesting that “Joe Bari” be changed to “Tony Bennett”—still marquee-friendly, but significantly more faithful to his given name.

There were a number of early Columbia hits, including but not limited to “Because of You” (1951), his first Billboard number-one; “Cold, Cold Heart” (1951), a cover of Hank Williams’s original; "Blue Velvet" (1951), which he was the first artist to record; and “Rags to Riches” (1953), which would later see a resurgence when Martin Scorsese put it in Goodfellas (1990). Bennett and Clooney were frequently partnered together to host radio and TV programs around this time, which meant that he quickly learned how to improvise, one of the skills he seems to value most in any entertainer. (It comes up a lot when he talks about Amy Winehouse and Lady Gaga in particular.) The ‘50s were similarly eventful on a personal level: he married his first wife, Patricia, and had two sons, D’Andrea (aka Danny) and Daegal (aka Dae). With his income so stable, he also got to make good on his childhood dream, buying a house for his mom in New Jersey. As he puts it, “I felt so proud that I’d finally achieved my life’s ambition: getting my mom to stop working. […] Everything else I’ve done ever since has essentially been a free ride.”

The things I read and watched build pretty consistent lists of Bennett’s quirks and convictions, his likes and dislikes. He’s worn a suit for his entire career, which is his way of showing respect for an audience. (He once put one on in the middle of the night… to evacuate a building… mid-earthquake.) He’s known for taking barely any time at all to cut a record, having spent weeks or even months preparing for a given recording session. As in his first Unplugged set, he’s often made a point of doing at least one song per show without a mic, again to emphasize that it’s an option for him. Likely owing to his upbringing, he isn’t that big of a spender, claiming that his only real splurge has been the Central Park South home where he’s lived for decades. He’ll tell you the name of every single musician he’s worked with, no collaborator too insignificant to acknowledge. (“Proper credit is important,” he writes in Life Is a Gift. “It’s one of the few things we can honestly say we deserve.”) While he never phrases it quite this way, he’s also a bit of an emotional vomiter, which I mean in a literal sense. The first time he saw Charlie Parker perform live, he writes in his memoir that he was “so intensely overcome with emotion at what [he] heard that [he] actually went into the alley behind the club and threw up.” In his 2012 book, he describes doing the same thing—getting “physically sick from excitement”—after hearing Lester Young’s music.

Tony Bennett likes: Charlie Chaplin, Louis Armstrong, Rembrandt, painting with an easel in Central Park, Count Basie, the pencils that David Hockney recommended he use, Lena Horne, Judy Garland, the whole notion of craftsmanship. Tony Bennett does not particularly like: his song “In the Middle of an Island” (1957), one of his biggest hits of the late ‘50s; media revolving around Italian mobsters (“I don’t like stereotypes”); Clive Davis, whose tenure at Columbia overlapped with his own long enough for Davis to emerge as a villain in both books; his album Tony Sings the Great Hits of Today! (1970), which comes back to the Clive Davis thing (“I literally regurgitated before the first recording session”); and demographic segmentation, as in… the entire concept of targeting a particular work of art at a particular group of people.

Beginning relatively early, Bennett started to take a sort of ‘If you build it, they will come’ approach to his work—wanting to focus on albums over singles, sidestepping trends whenever he had the option, and prioritizing jazz music and musicians. The business-minded people in his orbit (e.g. Davis) have not always appreciated this, so for the first couple decades of his career, he often negotiated deals in which he’d, for example, get to make a traditional jazz album in exchange for however many chart-friendly pop albums he delivered. (I should mention that Bennett and Davis appear to be entirely civil these days, with the former a frequent attendee of the latter’s annual pre-Grammys event.)

As I mentioned earlier, his story is also dotted with an unusual number of near-death experiences. During the war, he woke to discover that a massive piece of shrapnel had missed him by mere inches, and there were several moments on the line when someone else’s spur-of-the-moment decision saved his life. The earthquake he dressed up for was just one of three he’s found himself in. He happened to be elsewhere in the building when, during one of his shows in mid-revolution Cuba, a bomb went off on stage, severely injuring 35 chorus girls. In 1965, his friend Harry Belafonte invited him to join the last of the three Selma to Montgomery marches; he accepted, marching and then performing alongside Nina Simone, Sammy Davis Jr., and other celebrities. “When the march was over, we were all held up in a ‘safe house,’ and the various volunteers drove people to the airport or back to their homes,” Bennett writes in Life Is a Gift:

When it came time for Billy Eckstine and me to head out, we gave up our seats to others. We later found out that the driver was assassinated by the Ku Klux Klan on her way back. She was Viola Liuzzo, a white mother of five from Detroit who had come to Alabama to give her support. It was a horrendous tragedy that saddened us to no end.

(As a quick aside: he’d previously claimed in his 1998 book that Liuzzo was murdered after dropping him off at the airport—I have no idea why. But he nevertheless corrected the record in his 2012 one; the above version is backed up by Belafonte’s 2011 memoir as well as this video, in which the two men look back at the march.) In 1996, Bennett had a hernia rupture as he pulled up to—where else?—the White House, which gave noted Tony Bennett fan Bill Clinton an opportunity to play hero, having him shuttled to the hospital for emergency surgery. Combined with the famous friends that start disappearing around Bennett as you make your way through his life story, it sometimes feels as though he’d been designated immune in some sort of simulation. Or, as he often puts it himself: “Benedetto means ‘the blessed one,’ and I feel that I have truly been blessed.”

But to get myself back on track, it was in the ‘50s that Bennett became a superstar, but in the ‘60s that he was cemented as a legend. And neither feat was exactly a piece of cake, since it was during those same years that rock and roll took over the industry (in the form of Elvis, Beatlemania, and so forth). In 1962, he performed (and released the live album for) his now-iconic set at Carnegie Hall, the show co-directed by Arthur Penn. He also recorded the biggest hit of his career to date, “I Left My Heart in San Francisco.” The song became Bennett’s first gold record and turned him into a Grammy winner. (At the time of writing, he’s 19 wins deep, with five nominations at the upcoming ceremony in April.) It’s also considered by most people to be his signature one: “When people ask me if I ever get tired of singing ‘San Francisco’ I answer, ‘Do you ever get tired of making love?’ That usually leaves them speechless.”

Frank Sinatra recorded a version around the same time, but pulled it pretty soon after its release; it’s not hard to hear why. A few years later, the elder crooner would announce during an interview that Bennett was his favourite singer, one of the most flattering—and, as Bennett tells it, fruitful—things a performer of Sinatra’s stature could have done. As in the ‘50s, Bennett churned out work constantly during this decade, often multiple albums (and hundreds of live shows) per year. But his professional life had taken a toll on his personal one: he spent the second half of the ‘60s separated from Patricia. “The estranged wife of singer Tony Bennett has sued him for divorce on grounds of adultery and desertion after 17 years of marriage,” read a 1969 report. “The suit […] charges Bennett, 42, committed adultery with singer Sandra Grant [and that] Miss Grant is expecting Bennett’s baby.” (Bennett’s first daughter, Joanna, would be born the next year.) Clive Davis was also named president of Columbia in 1967, and the two men simply could not see eye to eye. The experience of recording Tony Sings the Great Hits of Today!—a project mandated by Davis, Bennett’s digestive upset be damned (here’s a snippet of the album for you)—was one of the last straws for the star in ending his two-decade relationship with Columbia, which he did in 1971.

That same year, he married Sandra, with whom he’d eventually have a second daughter, Antonia (herself a singer these days). The family spent some time in London while Bennett performed live shows and tried to get his own label, Improv Records, off the ground. He had the creative freedom he’d wanted, but, absent any sophisticated distribution infrastructure, struggled to match his past commercial success. Through these years, and especially once Davis left Columbia to found Arista Records in 1974, Bennett’s former label made multiple attempts to get him back—all of which he declined. Being in England meant that he could spend more quality time with his family. He also got serious (like serious serious) about his painting, resuming fine art instruction in the form of private lessons. (By the end of the decade, he’d be showing his art publicly, something he’s done periodically ever since.)

After Antonia was born in 1974, the family relocated to Hollywood, which came with its own perks—the Bennetts had neighbours like Fred Astaire and Ella Fitzgerald, the girls spending a lot of time around Ella in particular—but also its share of era-specific challenges. As Bennett recalls, “The seventies drug scene was getting out of control”:

At every big party I’d go to, people were high on something. Cocaine flowed as freely as champagne, and soon I began joining in the festivities. At first it seemed like the hip thing to do, but as time went on it got harder and harder to refuse when it was offered. Compounded with my pot smoking, the whole thing started sneaking up on me.

By the late ‘70s, he had a full-blown drug problem, one perhaps reinforced by the ways that his personal life had again crumbled. For one, his marriage to Sandra was on the rocks. (They’d separate in 1979, but their divorce wouldn’t be finalized until 2007.) On top of that, in 1977, his mother died, the news delivered to him just minutes before a show: “I was so overcome with grief that I actually wondered if I might be losing my mind. And I found that I was using drugs to ease my pain.” He began experiencing depressive episodes, and, around this time, stopped recording new music; he released Together Again (1977), his second critically acclaimed Bill Evans collaboration of the ‘70s, and then nothing in terms of studio work for almost a decade. He’d also more or less turned into a Vegas act by this point, not really performing anywhere but the Strip.

Between Improv’s fiscal problems and Bennett’s lifestyle, he ultimately found himself in debt to the IRS, having fallen behind on his taxes. Which brings us to the turning point in this story, roughly where mine would have started if I had the necessary restraint. One night in 1979, he writes, “The accountants called to say that the IRS was starting proceedings to take away the house”:

In frustration I overindulged [on cocaine] and quickly realized I was in trouble. I tried to calm myself down by taking a hot bath, but I must have passed out. And I experienced what some call a near-death experience; a golden light enveloped me in a warm glow. […] But suddenly I was jolted out of vision. The tub was overflowing and Sandra was standing above me. She’d heard the water running for too long, and when she came in, I wasn’t breathing. She pounded on my chest and literally brought me back to life. As I was rushed to the hospital, the only thought on my mind was something my ex-manager Jack Rollins had told me about Lenny Bruce right after Lenny’s death from an overdose. All Jack said was, “The man sinned against his talent.” That hit home. I realized I was throwing it all away, and I became determined to clean up my act.

The experience effectively spooked him into sobriety; he’s claimed since that there was no real physical recovery in store for him. “I didn’t have to hide to smoke or do other naughty things,” he said in 2011. “All of a sudden, I was just… honest.” (He tends to sidestep the overdose when asked about his days as an addict—that is, when he admits to having been an addict at all.) (In 2012, after Whitney Houston was found dead in her bathtub, having accidentally drowned while high the way Bennett almost did—and only half a year after Amy Winehouse’s death—he caused quite a stir taking a pro-legalization stance.)

It was here that both of Bennett’s sons, now in their 20s, entered the picture in a professional sense. While on the mend after his overdose, Tony called and asked if they’d come to Hollywood. “I recalled the great business advice that my son Danny had always given me,” he writes in Life Is a Gift, “and asked if he and my other son, Dae, would want to come to the West Coast to help me figure things out.” They arrived within 24 hours, and Tony made a point of not mincing words about his situation—the drugs, the (lack of) money, the stalled career. He wasn’t looking to retire, but he didn’t want to compromise his artistic integrity, either.

The first order of business was taking a look at Tony’s books. The numbers weren’t great, but fixing them was luckily a matter of basic budgeting. (“I’m not an accountant, but I’m a good common sense person,” Danny has said of this time.) A plan was negotiated with the IRS in which Tony could pay his debt off over a three-year period. Since Danny also happened to have ideas for how Tony could reignite his career, he took over as his father’s manager—a role he didn’t necessarily intend to remain in forever, but nevertheless has. As Tony puts it, “Danny’s kept me away from the negotiations and the corporate playing field so I could stick to making music.” More evocatively, Danny has likened himself to a sort of “dragon slayer.” (Dae, for his part, is a successful producer who’s mixed, engineered, and mastered many of his father’s records. He’s actually the more Grammy-nominated of the two brothers.)

Danny and Dae had been raised with their father’s values drilled into them, so the challenge ahead was really reconciling those values with the industry’s commercial demands. This was decently familiar territory, since they’d not only grown up around industry people but spent some of the ‘70s playing in the same band, Quacky Duck and His Barnyard Friends. (Through Warner Bros., they released one album before being dropped.) Tony was smart enough to know that it wasn’t the mid-‘60s anymore, but he wasn’t interested in changing any fundamental tenet of his act; he didn’t want to take the suit off, and he genuinely believed that the Great American Songbook was something worth hyping up. And, allergic to the concept of demographics as he is, he wasn’t looking to appeal solely to the listeners who’d grown up with him.

Danny’s response, in addition to moving Tony back to New York, was to focus on youth-oriented television: “He assured me that if we gave the young public an opportunity to get to know me, I’d once again be accepted by that audience.” It would take some time for the duo to wind up at MTV (launched in 1981), which—as I wrote last August when the network was turning 40—wasn’t immediately the career-making cultural phenomenon it would become. In the meantime, the Bennetts would make Tony ubiquitous on television in a general sense, the way he’d been during his rise to fame.

In 1982, he appeared on Second City Television (aka SCTV, Canada’s SNL equivalent that launched the careers of people like Eugene Levy and Catherine O’Hara). “Don't let one fall take you out of the fight,” he jokes knowingly during the skit where he appears. Just as he’d been one of the first guests of Johnny Carson’s back in 1962, he made a relatively early appearance on Late Night with David Letterman, “the hip talk show for college kids.” (“Naturally, I still did Carson every year. But Danny thought I should do the Letterman shows as well.”) Danny has said that there were multiple occasions around this time on which his father turned to him and asked, “Would Frank do this?” to which he’d respond, “Nope, and that’s why you’re doing it.” Steadily, Bennett & Co. launched a media offensive, reinstating Tony as a relevant public figure—often, though not always, by having him hobnob with younger ones.

“Even with no new records being released during these years, I was as busy as ever,” he explains. Part of the strategy, it seems, was making clear that Tony Bennett was a name worthy of buzz and respect with or without a big label behind it. A 1981 profile of the star in New York magazine had him breezily walking around the city with journalist Chet Flippo, pedestrians asking for autographs and cab drivers singing his hits out of their windows. “Although he’s cut 88 albums,” Flippo wrote, “Bennett is without a recording contract at the moment. The main reason is that he’s still idealistic enough to wait for a contract that meets his terms.” If there was one look Bennett wasn't going for, it was desperation.

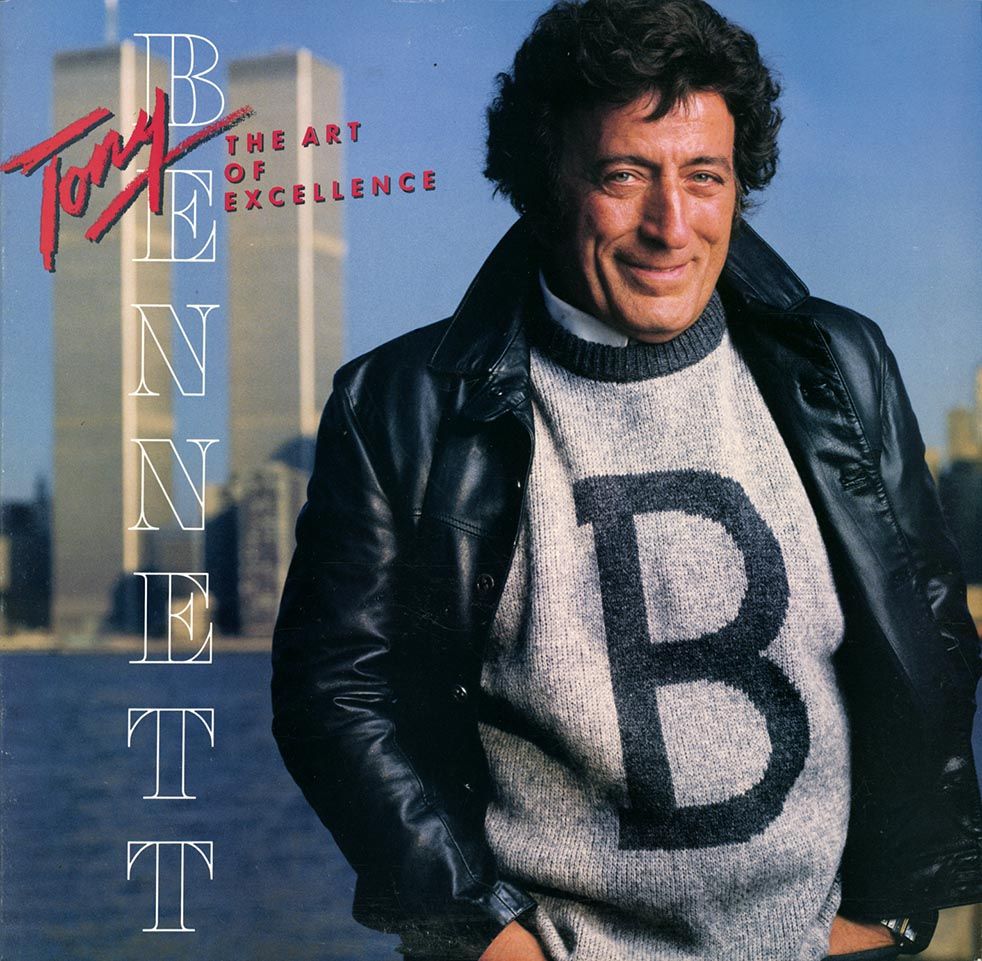

Halfway through the ‘80s, once the right terms were finally presented to them, Danny helped Tony reunite with Columbia. The latter then released his first studio album in almost a decade, ballsily called The Art of Excellence (1986), for which Annie Leibovitz photographed the 59-year-old in front of the Manhattan skyline. In hindsight, the album cover is funny for how it betrays the in-betweenness of the moment. Bennett is noticeably styled for a new phase in a “B” pullover and leather jacket, but look again and you’ll see that he’s actually wearing a dress shirt and pants after all, his collar peeking through just so. (Beginning with his next album cover, he’d be back to a traditional suit, which has virtually stayed put since.)

Piece by piece, the things that would permanently keep the Tony Bennett engine running were locked into place. He’d clearly found the right manager, was now back with his hometown and his label—the Central Park home would come a bit later, in the mid-‘90s—and had once again reached TV staple status. It was also in the ‘80s that he started dating Susan Crow, a lifelong fan four decades his junior, who’s at this point been his companion for almost 40 years. (She wouldn’t become Susan Bennett until 2007, the same year that his divorce from Sandra was finalized.)

Things continued this way for the next while, with Bennett typically releasing collections of standards in the form of easily marketable concept albums, which started to win him Grammys again: Bennett/Berlin (1986), a tribute to Irving; Perfectly Frank (1991), whose album cover has him staring up with reverence at his idol; and Steppin’ Out (1992), released around the five-year anniversary of Fred Astaire’s death. In 1990, Bennett became the first-ever animated special guest on The Simpsons, which introduced an even younger crowd to his name and voice. That year also saw the release of Goodfellas, whose opening sequence is backgrounded by “Rags to Riches.” The star had approved the needle drop but would later say that he “didn’t like” the song’s use, citing his general distaste for fictional Italian mobsters: “I know how great the actors and the story were, but it’s not accurate because every nationality has an underworld. It’s not just the Italians.” (When, later in the decade, he was “offered a fortune” by HBO to license his music for The Sopranos, he declined.) (This whole story might actually be more complicated.)

One day, Danny has since recalled, Tony walked into his office and said something along the lines of, “You know, I was watching on MTV… I think I can do really well.” Danny was then left alone to chew on that. After some back-and-forth with the network, it was arranged that Tony would film an advertisement for its long-running “I Want My MTV” campaign in 1988. In a fun bit of foreshadowing, he took Cole Porter’s “I Concentrate On You”—a song that appears on Love for Sale with Lady Gaga, whom you could get away with calling one of the first post-MTV superstars—and tweaked the lyrics for the occasion.

Without getting too much into genre, the concept of music television wasn’t exactly foreign to Bennett, having come of age as a star alongside television itself. Back in the late ‘50s, he’d filmed a prototypical music video in which “Stranger in Paradise” played as he walked around Hyde Park. (If it exists anywhere, I haven’t been able to find it.) “The clip was distributed to all the local TV stations in the U.K. and America,” he explains, “where it was aired on shows like Dick Clark’s American Bandstand.” As I wrote last summer during another one of my MTV instalments, “Music videos as we know them had originally come out of the desire to not have to travel for every single televised performance—something that was tiring and often expensive, especially if you were, for example, an Australian artist wanting to reach your American fans.” Bennett’s “Stranger in Paradise” clip was an early example of what that looked like in practice.

Around the same time as his MTV ad, he started to play around with the format as it had evolved to exist; “Where Did the Magic Go?” from Astoria: Portrait of the Artist (1990) is a good example, as is “I’ll Be Seeing You” from Perfectly Frank. (To my knowledge, neither of those were played on MTV, and it’s hard to say whether they were even sent the network’s way for consideration.) There seem to have been other seeds for Bennett’s next chapter planted around this time, like how he performed at the Hard Rock Café right after the Red Hot Chili Peppers in 1989. “Bennett must have felt good getting cheers from a new generation of twentysomething fans,” wrote Jeannine Stein in her L.A. Times write-up of the event, which was hosted by Spin. Another seed was how, in the early ‘90s, he was often photographed with Mariah Carey by way of then-husband Tommy Mottola, at this point the top dog at Columbia.

Eventually, Danny booked Tony for a decidedly homoerotic appearance at the 1993 VMAs, where he presented an award with Anthony Kiedis and Flea, the two acts having switched outfits. (Bennett belly-laughs while Kiedis fits a whole banana in his mouth.) “These guys are hot,” Bennett told Kurt Loder that night in his distinctive New York accent. “And they’re chili… and they’re peppers!”

A week after the broadcast, the response to his appearance overwhelmingly positive, MTV called to let Bennett know that they were going to add “Steppin’ Out with My Baby” (1993), a new video he’d made, to Buzz Bin—“considered the hippest show on MTV, usually reserved for ‘cutting edge’ rock acts.” The video had actually been produced with the network in mind: “I wanted to come up with something sharp and snazzy enough to compete with the other videos on MTV, so we hired video director Marcus Nispel.”

Nispel was then an up-and-comer who’d already helmed things for people like Mariah Carey and George Michael, whose work Bennett would need to match in terms of quality. He arguably had a Fincher-esque sensibility as a director, which might be why “Steppin’ Out with My Baby” looks more than a little like Madonna’s “Vogue” (1990). (It similarly features ballroom icons Jose and Luis Xtravaganza, so it’s not necessarily that much of a reach.) While I swear that I didn’t plan any of this, more than one of Bennett’s videos in the ‘90s would have a Madonna connection: the one for “God Bless the Child,” a duet recorded with a long-since-passed Billie Holiday, was directed by Madonna’s brother and sometimes colleague, Christopher Ciccone.

The Unplugged gig was a natural extension of all of this. In April of 1994, Bennett filmed his set, inviting k.d. lang and Elvis Costello to join him on stage for duets of “Moonglow” and “They Can’t Take That Away From Me,” respectively. (The next month, the New York Times reported that several big MTV artists had tried for a guest spot.) The episode didn’t just go over well; it was the show’s second-highest-rated one yet. The live album MTV Unplugged was released in June, not only going platinum but taking home Album of the Year at the 1995 Grammys—one of only four live albums to ever do that. When Bennett hears his name announced during the ceremony, he kisses Susan and then shakes hands with Danny and (presumably due to sheer proximity) Bruce Springsteen. “There are no words,” he says during his speech. “It’s such a victorious feeling to sing good, American music and have this happen. Thank you very much.”

“We don’t like to use that word ‘comeback,’” Danny had told the Times following the Unplugged taping, to which Tony added: “I never went anywhere.”

Until recently, Bennett never really lost this momentum, having said many times over the years that he had zero intention of retiring. He’d make many more youth-oriented cameos as himself in the ‘90s and into the new millennium: Sesame Street, Muppets Tonight, Analyze This (1999), Bruce Almighty (2003), Entourage (“it’s silly,” he once said of the show), American Idol, 30 Rock. (He’d done a bit of acting proper in the past, but Cary Grant once advised him never to seriously pursue it, guessing—probably correctly—that he’d be bored out of his mind having to do so much waiting around on sets.) Bennett has also managed to remain an awards show mainstay, seemingly regardless of whether he’s among the nominees at a particular event. As just one example: in late 1996, Madonna told Billboard that she’d only accept a career achievement award from the magazine “if her favorite singer, Tony Bennett, presented [it] to her.” As he tells the story in his memoir:

I was really knocked out. I’ve always admired Madonna. I think she’s a great artist. The way she continuously reinvents herself is amazing, and I was honored that she wanted me there with her when she got such a prestigious award. I met Madonna in Los Angeles and we flew to Vegas together on her private plane. She was very sweet, but since it was the first time she’d been away from her newborn baby, Lourdes, she was really anxious, so we ended up talking about the baby for most of the flight.

“Are you sure that I’m not supposed to be giving this to you?” she turned to him and asked during her speech. This is as good a time as any to mention that the two had been acquainted since at least 1992, when they were photographed together at a party that Madonna hosted in k.d. lang’s honour. (They appear to have remained friendly since; as recently as 2016, Madonna sent in a message for one of Bennett’s television specials, something she appears to do whenever asked.)

Then, there are obviously Bennett’s own accolades, which are legion: he’s a Kennedy Center Honoree, has two Emmys, and—in a statistic worth sitting with for a second—has won the majority of his Grammys in the 21st century (one is the Academy’s Lifetime Achievement Award). And while third parties often frame his accomplishments through a sort of ‘Old Man Still At It’ lens, the star himself doesn’t really court that framing, with the exception of maybe having released a couple things to coincide with milestone birthdays. He’ll make the odd joke about his age here and there—he once interrupted the Red Hot Chili Peppers while they were mid-interview to yell, “Hey! My mom has all your records!”—but it seems to be an afterthought for the most part.

“A lot of people look at me and go like, ‘What are you doing? Leave him be!’” Danny said of his father not too long ago. “And I’m like, ‘It’s not me!’ I mean, seriously, I’m very conscientious of his age. The guy doesn’t like to take elevators, he doesn’t like to take escalators. […] Keeping up with him is a challenge.” Corroborating this in 2008, Tony told GQ that he “could have retired ten years ago quite comfortably” had he wanted to. “But I like doing it. I like entertaining people.”

Aside from Bennett’s music, a lot of his energy in recent years has been spent on his other medium of choice. “If you have ever wandered below [his] fifth-floor studio window, there’s a chance he has painted you,” wrote Margaret Guroff in a late-aughts profile. “The artist snaps photos of street scenes for inspiration and tries to capture their light in oil or watercolor.” Bennett writes in his memoir that he’s usually “working on three paintings at once, so [he doesn’t] get burned out on any one piece.” He also claims to have amassed a body of work of over 800; that was in the late ‘90s, so the number would be a three-digit one now. If you’ve ever been to the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., you may have walked right by one of his paintings. He signs all of his visual art “Benedetto,” like it says beneath a rendering he once did of Miles Davis’s trumpet, which Lady Gaga had tattooed on her right bicep in 2014.

If painting isn’t an option in a given moment, he’ll sketch. The films I watched would suggest that anyone and anything in his vicinity is at risk of being immortalized on a napkin or some sheet music. In one recording session chronicled in the documentary The Zen of Bennett, Willie Nelson can’t quite figure out what Bennett is up to behind his music stand, uneasily aware that he’s under scrutiny. “I’m doing a sketch of you,” Bennett explains, no explanation provided beyond that. (“Oh, that’s what’s going on, okay,” says Dae from the control booth, in a tone conveying that this happens often.) More recently, Bennett did the same thing to Gaga while shooting the artwork for Love for Sale, so the final album cover has him showing the camera (wielded by Kelsey Bennett, Danny’s daughter) the sketch in question.

The bedrock of Bennett’s 21st-century shtick has been the duet, and especially the duet album. These tend to be made up of songs that he’s recorded before, as is how the whole Great American Songbook thing works. But they never feel unoriginal because he, like a lot of his fellow jazz greats, has made a point of never recording (or even singing) a song the same way twice; the idea of these standards is that they can be slowed down, sped up, have their pronouns or proper nouns tweaked to change their meanings, and so on.

Bennett has historically squeezed new things out of older songs by fabricating backstories for them, or imagining their lyrics as autobiographical. When he sang “One for My Baby (And One More for the Road)” with John Mayer on Duets II, they consciously pretended to be two drunk guys going back and forth at a bar, as Bennett explains during the making-of documentary. (Mayer, incidentally, provides one of the best summations of Bennett’s work I’ve encountered: “The Tony Bennett sensation is the sensation of being sung to and made to feel safe. That’s a really excellent feeling: to be safe inside of a singer’s voice.”)

Bennett has recorded albums with prominent jazz names like Diana Krall and Bill Charlap, but his duet releases have mostly seen more traditionally poppy acts do a stint in his world for a change, in what’s arguably the inverse of his MTV party-crashing days. Lady Gaga and k.d. lang have gotten whole albums to themselves (two in Gaga’s case), but the average one has featured at least a dozen different names pulled from all over the music world. Tim McGraw and Elton John will appear together on the same album (Duets: An American Classic [2006]); ditto Andrea Bocelli and Queen Latifah (Duets II). However scattered these names can feel, they’re always united by the Great American Songbook, and of course Bennett himself. (That said, the duet partners on Viva Duets [2012] all come from the Latin music space.)

In terms of promoting these projects, Bennett has moved away from filming traditional music videos—not that he ever made many to begin with—to documenting his recording sessions, which can be packaged as individual clips or feature-length specials later on. There’s a marketing thing happening here by default, since he in some ways absorbs the audiences of his duet partners. Maybe you don’t think you’re all that inclined towards the Great American Songbook until one of your favourite artists—be they Faith Hill, or Mariah Carey, or Carrie Underwood—forces you to give it a second chance. That’s obviously useful as far as being prompted to explore Bennett’s own catalogue, but it dovetails with his mission to keep these songs alive more generally.

All of that said, sales don’t seem to be the driving factor in how these names are chosen, nor does the desire to have the most possible variety or novelty on a single album. What matters first and foremost is how these artists contrast with the star himself. “Making a duet album, there’s a game to it that makes it work,” he explains at the beginning of the Duets II film:

The whole thing is that both singers have to be different. When you hear Louis Armstrong with Ella Fitzgerald, she sings sweet and he sings raspy, like a trumpet solo rather than a vocal. The success of a duet album is the difference between each person. [...] The contrast of one calm singer, next to one that’s going all over [the place], makes it happen.

Provided that there’s a real talent behind any theatrics, bells and whistles don’t seem to turn him off of a duet partner. A compelling performer is a compelling performer, and he’s said that he gravitates to anyone who clearly lives to entertain others. I find this interesting in light of how Bennett has been surrounded by so-called divas his entire career—from Pearl Bailey, Sarah Vaughan, and Ella Fitzgerald earlier on; all the way through to Céline Dion, Barbra Streisand, and Elton John more recently. As he writes in Life Is a Gift, “‘Vive la différence,’ I love to say. Hanging out with people who aren’t exactly like you keeps life interesting, and also keeps you on your toes.”

Bennett’s duet partners have taken wildly different journeys to end up in the studio with him. There are the repeat collaborators whose voices and company he obviously enjoys: k.d. lang, Elvis Costello, Michael Bublé. Others are people he’s known for decades, like Stevie Wonder and Paul McCartney. (Krall and Wonder have separately been part of McCartney’s Bennett-esque project, Kisses on the Bottom [2012], whose Jonas Åkerlund-directed concert film I watched as part of my thesis research.) Amy Winehouse first thanked Bennett in the liner notes of her debut album, Frank (2003), and he’d later present her with her first Grammy in 2008, but it took until 2011 for them to work together. While it never came to fruition, Bennett and Beyoncé seemed to have plans to collaborate; he started saying so in interviews in 2016, about a year after he was filmed snapping along to her Stevie Wonder tribute. (He’d been a Kennedy Center Honoree the same year as Tina Turner, so he may have set his sights on Beyoncé quite a bit earlier.)

Another collaborator scouted at an industry event was Gaga, a fellow performer at the Robin Hood Foundation gala in May of 2011. In a set that had up until then included things like “Americano” and “Judas”—for context, this was the same month that she released Born This Way (2011)—she performed a rendition of “Orange Colored Sky,” a song made famous in the ‘50s by Nat King Cole. (He was a friend of Bennett’s, and his late daughter, Natalie Cole, appears on Duets II.) Like Amy, Gaga had been raised on Bennett’s music, so it was a big deal for the whole Germanotta family that he asked to meet them after seeing Gaga perform that day. By the end of July, they’d recorded “The Lady Is a Tramp.”

To look at the marketing thing from the other side, it can be a massive boost in a given moment—commercially, but more so on a branding level—for an artist to work with Bennett. It didn’t hurt for Christina Aguilera to link up with him during her Back to Basics (2006) era, where the whole concept was to nod to a bygone period of entertainment. While Gaga was in many ways on top of the world when she first met the crooner in 2011, that certainly wasn’t true when they reunited to record Cheek to Cheek a couple years later. As early as 2008, the year Bennett cameoed on Entourage, there was already an understanding that his collaborations with younger chart-toppers went both ways. The episode in question revolves around a pop star, Justine Chapin (played by Leighton Meester), who’s doing a duet project with Bennett to switch up her image. “Very sophisticated… grown-up,” she explains of the new vibe.

Even for someone like Amy, whose talent was never called into question in exactly the same way as some of these other names, Bennett’s support and kindness while she was around to experience it sticks out in retrospect; it was a lot trendier at the time to make fun of her. In footage from their March 2011 recording session that appears in The Zen of Bennett, Amy is a mess of nerves when she first joins him in the studio for “Body and Soul.” The younger star was famously hard on herself, and, unhappy with her first couple of takes, tells the older one that she doesn’t want to waste his time; for a second, it seems like she might actually pull the plug on the whole collaboration. (Amy features this same moment.) Knowing that she’d been raised on jazz, Bennett guesses—correctly and then some—that she might appreciate hearing an anecdote about Dinah Washington. The gesture loosens Amy up enough that it literally saves the session. (In August of that year, Bennett would preview a snippet of the video during the VMAs.)

“Of all the contemporary artists I’ve worked with, she has the most natural jazz voice,” Bennett told the Guardian a few months later. “But I’d like to talk to her, and what I’d like to say to her is very personal. I’ve also had a moment of insecurity and darkness, and was able to pull out of it.” On July 23, a few weeks after his Guardian interview, Danny called to let him know that she’d died. (Her official cause of death was listed as alcohol poisoning.) Tony was apparently devastated, and something like regret has been palpable in every interview he’s given about it since. “Sometimes—sometimes—someone will say something that strikes home on just the right day,” he writes in his most recent book, Just Getting Started (2016). “I said nothing on the day that I might have had a chance.”

It was on July 31, only eight days after Amy’s death, that he recorded “The Lady Is a Tramp” with Gaga.

The video for this first collaboration with her plays differently, at least to me, once you know this. Bennett needed a boost in that moment, and he seems genuinely amused by Gaga as she dances around their recording setup with a glass of brown liquor. “The chemistry between us was all sparks,” he’d later remember of the session in Life Is a Gift.

It was here that I wanted to loop in my friend and fellow pop culture writer, Coleman Spilde, one of relatively few people I know who can speak to both Gaga and Bennett at length. Coleman has been a Jazz Appreciator for far longer than I have, and was actually one of the first people I told about this project, way back in August of 2021. His teenage years were similarly Gaga-centric—we’re roughly the same age—but while it took me until relatively recently to do my Bennett catch-up, Coleman started his around the same time as the duo started collaborating. “I had heard Tony peripherally, mostly—I was aware of his legend status in the industry and had heard a few of his songs on jazz stations that my dad and I used to listen to in the car,” Coleman told me. “Once Tony and Gaga began working together, I deep-dived on the Bennett archives and was stunned at the staggering amount of nuance in his storied career.”

The so-called lady and the legend—the “flamboyant pop star” and the “gentleman jazz singer,” as they were described in a 2014 Sunday Morning segment—are almost exactly 60 years apart in age. But while the two are often discussed as if they may as well be from different planets (“unlikely” gets used a lot to describe their relationship), they have far more commonalities than differences. There’s their shared Italian-Americanness (and the fact that they both swapped Italian-sounding given names for stage ones), their New York City upbringings, their fluency in pop and jazz music, their struggles with addiction, their respective strings of failed relationships, and so on. As the Sunday Morning segment pointed out, in 2014 they were even neighbours in Manhattan; you could see Gaga’s building from Bennett’s window.

They’re both also goofballs! The idea that the buttoned-up crooner merely tolerates the younger star’s idiosyncrasies is a misread or even flattening of Bennett’s personality; he very much has a rascally side. In one scene from The Zen of Bennett, his friend—a fellow 80-something—tells him, “The girl out there that’s doing makeup and doing people up and touching [them] up, she’s from Queens.” “Oh yeah?” Bennett asks before taking a second to prepare his response, looking around the room to see if anyone’s listening. “If this was 40 years ago…” he says, leaning in and trailing off so that the two men can share a good chuckle. We’re talking about the same Tony Bennett who, on stage with Gaga in 2015, interrupted her while she was singing to say, “I read in the papers you said you were horny today.” (She had indeed.) In interviews and other live settings, they’re constantly trying to crack each other up.

But to come back to the music, one of the things that Bennett seems to appreciate most about Gaga, interestingly, is the fact that she was to some degree formally trained. (She’s technically a New York University dropout, but it’s true that she studied music there.) He reiterates often that he believes in breaking rules and making things your own, but only after you’ve mastered the rulebook. When it comes to jazz, being able to improvise is one of your biggest assets, but first you have to “learn the ink”—what’s there on the page—as Gaga has put it in recent interviews.

“The Lady Is a Tramp” had the effect of publicly reintroducing the enigmatic superstar known as Lady Gaga to the world. At this point a few years into her music career proper, it was more than clear that she could make a dance floor banger, but discussions about her artifice and stunts tended to eclipse ones about her musical prowess. (That she’d been singing jazz since she was a kid was information you had to go looking for, and may not have necessarily guessed unless you happened to see something like this on YouTube.) “Tony gave her the chance to showcase her very best asset—her voice—to those who might not have realized there was a powerhouse jazz vocalist underneath the raw meat,” summarized Coleman. The enthusiastic response to “The Lady Is a Tramp” was an early domino in a very long chain of them, which you can use to plot the last decade of her career.

By the end of 2011, Gaga had posed nude for Benedetto the visual artist, as captured by Annie Leibovitz for Vanity Fair. “She was a natural model—and I'll tell you, she was as professional and elegant undressed as she was dressed,” he writes in Life Is a Gift. “We had a lot of fun together, and we have since become great friends.” Their blossoming friendship meant a lot to Gaga on a personal and fandom level, and was obviously flattering as far as it doubled as an endorsement of her talent, but it would soon emerge as a sort of lifeline—personally as well as professionally—as she went on to experience one of her first real struggle eras in the public eye.

The two began recording Cheek to Cheek, a purposely all-over-the-place tour through the Great American Songbook, in the spring of 2013. The decision to do an album together had, per Bennett, been made very early in their relationship. While in hindsight it’s curious that she was working on these two particular projects in tandem, it was in November of that year that she released ARTPOP (2013), a top-tier but risky album tasked with following up the cultural phenomenon that was Born This Way. As Coleman remembers ARTPOP, or at least how it was received immediately upon its release—time has been very kind to it since then—the album “was an almost legendary misfire among critics and most audiences, its EDM-heavy sound and lyrical content about drugs, trauma, and sexual assault proving too abrasive for many.”

There were other things going on in Gaga’s life around the same time, including but not limited to the grisly hip injury she’d sustained during her Born This Way Ball, and how she’d parted ways with her long-time manager, Troy Carter, in the days leading up to the album’s release. By her own admission, she finished out the year severely depressed. “Fans could tell that Gaga had lost a spark and that the energy that drove her messaging and art was quickly waning,” Coleman said. As she’d later offer herself, “I didn’t even want to make music anymore.”

She’d still take ARTPOP on tour in 2014, but the era ultimately felt like a condensed one compared to Born This Way’s two straight years of activity. Cheek to Cheek was released in September, Gaga still very much mid-tour, and by then there had already been two singles: “Anything Goes” and “I Can’t Give You Anything But Love.” It seemed, in other words, like she was perfectly content to jump ship from ARTPOP. “I just want to be happy,” she explained that year. “And I can’t tell you how happy singing this music makes me.” Of the two projects released during that same eligibility period, Cheek to Cheek would be the only one to receive a Grammy nomination, later winning Best Traditional Pop Vocal Album—the category where, statistically, you do not want to be nominated the same year as Tony Bennett. The two thereafter embarked on their Cheek to Cheek Tour, which ran from December of 2014 to August of 2015. (Shortly after that, they co-starred in this Åkerlund-directed Barnes & Noble ad; I’d completely forgotten that Bennett had been a small part of my thesis research.)

While Gaga wasn’t by any means the first pop star to benefit from an association with Bennett, she might be the winning example in terms of scale. Far from doing a quote unquote stint in his world, those early projects together changed the trajectory of her career, unleashing a whole new wave that she’s still riding more than a decade later. (As I send this out, she’s gearing up for another Jazz & Piano leg of her Las Vegas residency.) Coleman described the Cheek to Cheek era to me quite usefully as less of a way out and more of a way through.

Bennett once said himself, “Through [Gaga] telling her audience how much she likes me, all of them became fans of mine, all these young teenagers. On the other hand, by her singing these beautiful songs on the album, the audience I have, all of them said, ‘God, I never knew she sang that wonderfully.’ So we both helped one another.” She’d brought him some welcome joy during that first recording session back in 2011; to say that he’s since repaid the favour would be a massive understatement.

The plans for Love for Sale, nominated for Album of the Year at the upcoming Grammys—as well as Best Traditional Pop Vocal Album, of course—were originally laid back in 2014. Bennett reportedly called Gaga after Cheek to Cheek debuted at number-one on the Billboard 200 and suggested that they do another album. Finally released this past fall, Love for Sale is a collection of songs by legendary songwriter Cole Porter, making it the more conceptually cohesive of the two projects.

According to Gaga, the album was recorded mostly in 2018, with musical tweaks coming later. (She’s wearing her engagement ring from Christian Carino—someone she broke up with three years ago—in all the footage that’s been released of the two artists in the studio, and in most of the album’s promotional photography.) As Gaga summarized the process for Zane Lowe on the night of its release:

I’m really happy that we made it when we made it. We made this album—the guts of it, with the arrangements for all of the songs, with his quartet and my quintet—that was done inside of seven days. And then for a full year, there were orchestral arrangements made by Jorge Calandrelli and big band arrangements made by Marion Evans. And we’ve been fine-tuning it ever since.

By “when we made it,” she obviously means before Bennett’s Alzheimer’s had progressed to the point that he could no longer do this kind of work. Back in 2016, he’d remarked to his wife that he was having trouble remembering the names of his musicians. Though Susan wasn’t worried, chalking it up to her husband’s age—he turned 90 that year—he insisted on seeing a doctor. Gayatri Devi, a New York City-based neurologist, diagnosed him with Alzheimer’s shortly thereafter.

Bennett’s family—and also Gaga, who’s known about his condition since at least 2018, when they began recording the album—kept this a secret until AARP helped them reveal it on their own terms in February of 2021. That was largely because, in the four or so years between his diagnosis and the onset of the pandemic, he was still well enough to maintain his work schedule, as Devi recommended he do upon diagnosing him. As she said last summer in a 60 Minutes segment with Anderson Cooper, singing in particular is a “whole-brain activator” because of how it at once stimulates the separate parts of the organ related to hearing, movement, and even vision. On top of that, when it comes to Bennett specifically, being a performer is “an area of his brain that gives him real meaning and purpose in his life, and it’s imbued with emotion.”

Aside from continuing on with Bennett’s planned live shows, which Devi says “kept him on his toes and also stimulated his brain in a significant way,” it was arranged that his long-time collaborator, Lee Musiker, would run through a 90-minute set with him a couple times a week (indefinitely, so they’d still be doing that these days). From 2016 through 2019, nothing ever seemed amiss during live performances—this is still largely true, as I’ll get to in a second—and Bennett was still giving interviews. As has been the case for millions of people living with such conditions, however, the pandemic was “a real blow from a cognitive perspective,” Devi told John Colapinto for his AARP piece last year. “For someone like Tony Bennett, the big high he gets from performing [had been] very important.” Last summer during the 60 Minutes segment, it appeared that he was no longer quite so conversational, for the most part only able to answer simply phrased questions. (That said, he still manages some silliness.) While he sings all the time, he scarcely paints anymore, and will sketch only “a little… if he’s prompted,” says Susan, who’s now his full-time caregiver.

Despite his more recent decline, however, Bennett still reverts to what his loved ones call “the old Tony” when he hears anything in the repertoire of the Great American Songbook; because he’s been singing it for so long, Devi assumes that it’s at this point “innate and hardwired” in his brain. We’re shown in the segment how, when Musiker starts playing the piano in Bennett’s living room, the star comes whipping down the hallway, flashes the camera a thumbs-up, and begins singing. Cooper tell us that Bennett would go on to rehearse an hour-long set without any on-paper help—no music, no lyrics. Colapinto had written, “Music’s peculiar power to reach even severely afflicted dementia patients, stirring memories and reestablishing connections to those around them, is well documented but not well understood.” So, in addition to being usefully stimulating for the brain, it can bring patients and families dealing with the disease some respite. (This was one of the main topics of discussion when Zane Lowe—whose mother has dementia—spoke with Gaga—whose grandfather had dementia—for Apple Music ahead of Love for Sale’s release.) As Susan told Cooper, Bennett has “devoted his whole life to the Great American Songbook, and now the Songbook is saving him.”

There seem to have been two main reasons behind the Bennetts’ decision to break their silence about Tony’s diagnosis last year. For one, there’s an implication in the AARP piece that they’d like to quell some of the stigma around Alzheimer’s by being open about their experience of it. The fact that it’s so stigmatized, Colapinto explains, causes many patients to “retreat from the world,” something that isn’t recommended—neurologically speaking—when you have the disease. (“Keep routines in line with what the person with dementia has done for most of their life,” articles on the topic typically recommend.) The other big reason behind the silence-breaking was the album itself. Love for Sale was by that point finished, but the public would inevitably have questions when it came time for things like promotional interviews, which Bennett would have to sit out.

The AARP announcement clarified that the decision to reveal Bennett’s diagnosis was necessarily made without him. Aside from that, we—the public—have no idea what had been laid out by the Bennetts prior to then. By which I mean: when you’re diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, among the first things you’re typically advised to do is what’s called advance care planning, i.e. imagining various what-if scenarios and putting things in writing based on them. That planning is no one’s business but the Bennetts’ and theirs alone, which makes it tricky to talk about the decision to have Tony perform three live shows last summer with Gaga—an Unplugged episode in June, and two shows at Radio City Music Hall in the first week of August. (They were billed as the star’s final performances, and his family officially announced his retirement a week after the Radio City shows.)

In September, Variety reported that Gaga and the Bennetts had partnered with ViacomCBS—the conglomerate that owns, among other things, MTV—to release those performances as two specials: the Unplugged episode, which was released in December, and One Last Time: An Evening with Tony Bennett and Lady Gaga, which was released in November. The third and final project in the same deal is The Lady and the Legend, the forthcoming documentary about the duo’s 11-year relationship. It seems that the main logic with all of this, aside from trying to change the conversation around Alzheimer’s, was to make sure that the 95-year-old got a public send-off that felt appropriately triumphant. Danny, who came up with the idea to do the three shows, told Anderson Cooper that it wasn’t a decision made lightly, and that it came down to not liking any of the alternatives: “The pandemic was a big… it was a big thing for me. Ending his career on that note… [...] [it] couldn’t end that way, after all that he did.”

In what seems to be an intentional full-circle moment for Tony, the music videos from Love for Sale have been premiering via MTV, and the Unplugged episode brings things back to the moment in the ‘90s that solidified Bennett’s quote unquote comeback. As in his first episode, the more recent one saw him perform a solo rendition of “Fly Me to the Moon”—not mic-less this time around, but still very much the set’s emotional centrepiece.

In the special chronicling the Radio City shows—the second night of which coincided with Bennett’s 95th birthday—Gaga performs for a while by herself, and then her usual musicians are switched out for Bennett’s so that he can perform by himself. When Gaga eventually rejoins him on stage, Bennett yells out her name upon seeing her, and, when she spins around to show him her outfit, asks her to do it a second time. Eventually, once they reach the end of the set, she tells him, “Tony, we’re all so grateful to have witnessed your talent, your generosity, your creativity, and your kindness, your service through all the years. [...] Mr. Bennett, it would be my honour to escort you off the stage.”

I’m not especially interested in dictating how anyone should feel about this most recent chapter, since it’s not really my place, and I don’t think it’s all that simplistic to begin with. There are perhaps ethical question marks about some of it (e.g. last summer’s live shows, which Bennett does not remember performing), but definitely not all of it (e.g. Love for Sale itself, which had been finished long before then), and I do think it’s unwise to either a) conflate these two very different chapters, or b) spin something that might be uncomfortable—misguided, even, though it is taking place under medical supervision—as something malicious. (In case it was unclear, there’s been a bit of both online in the last year.) It’s worth keeping in mind how much information we don’t have, that certain conversations can’t and shouldn’t be had in 280 characters, and that these are real people having to navigate a monumental loss while in the public eye. And while this could (and may) of course change, none of the naysayers thus far have been professionals, at least to my knowledge.

When I asked Coleman how the Love for Sale era feels different compared to the Cheek to Cheek one—aside from the obvious thing—he responded that it seems to be “less about proving a point and more about taking a well-deserved victory lap for both artists. [...] Gaga wants Tony to share the shine here, and the same can be said for how she’s approached their promotional efforts.” Indeed, even though Gaga is the only one able to be interviewed about the album, and by default doing most of the talking, it’s Bennett’s life and career being foregrounded in the messaging.

To help myself get through this final chunk of the project, and maybe to reward myself preemptively for getting through it, I splurged on the limited edition Love for Sale box set (and maybe also a sweater). There’s the record itself on vinyl; everything else in the box is a sort of love letter to not only Tony Bennett but Anthony Benedetto—sketching tools that I’ll likely never use but am happy to keep around, photographs of Gaga and Tony taken by Kelsey Bennett back in 2018, and an overwhelming number of Benedetto prints. I think that I’ll probably have one framed to put up in my workspace.

This has become the sort of project for me where it’ll be fine—truly—if not a soul reads it. It by no means started that way, since, as I mentioned thousands of words ago, it hadn’t been my plan to write my own abridged biography of Tony Bennett (where the author seems to have a serious pop diva bias, though perhaps one he’d appreciate in light of his own). While my research/stewing period was obviously on the longer side… long enough that it’s not an exaggeration to say my loved ones have been looking forward to this day for months… I actually wrote the bulk of this in the last couple of weeks. What I’d been struggling with was moving everything out of my head (and my stress dreams—I wish that were a joke) and onto the page. I think it’s just that the stakes have felt significantly higher than usual. In the end, I’m very grateful to have been able to write so much of this in the present tense; if my deep dive was initially prompted in February of 2021 by a sense of regret, I now get to feel something a lot more like contentment.

It’s a testament to Bennett’s life and career that I’ve put this many words down and still feel like they’ve only scratched the surface. Please forgive me for my narrative ellipses, but perhaps you’ll do your own poking around in the Bennett archives. There was a lot that I didn’t cover or couldn’t find a way to—other things about his children and grandchildren and their careers, his non-profit and charity work (he’s been nicknamed “Tony Benefit” in philanthropic circles), and of course the majority of his musical output. As is usually the case with projects like this, one of the more fascinating aspects was how it contextualized or even totally recast some of the art I grew up with. For instance, I now realize that Bennett was part of “We Are the World 25 for Haiti” because he’s a long-time friend of Quincy Jones, and his work with Amy and Gaga will obviously never read the same.