Stephanie Phillips on Solange’s Offbeat Pop Stardom

If there are a dozen books on my bookshelf that have a Knowles family member somewhere on the cover, I’d probably only wholeheartedly recommend a handful of them. And while that’s a conversation for another time because I’m feeling peaceful, hopefully it helps explain why it’s such an honest-to-God pleasure anytime the latter pile grows. (I feel myself turning into Beyoncé that time she teased a plant-based lifestyle like it was new music.)

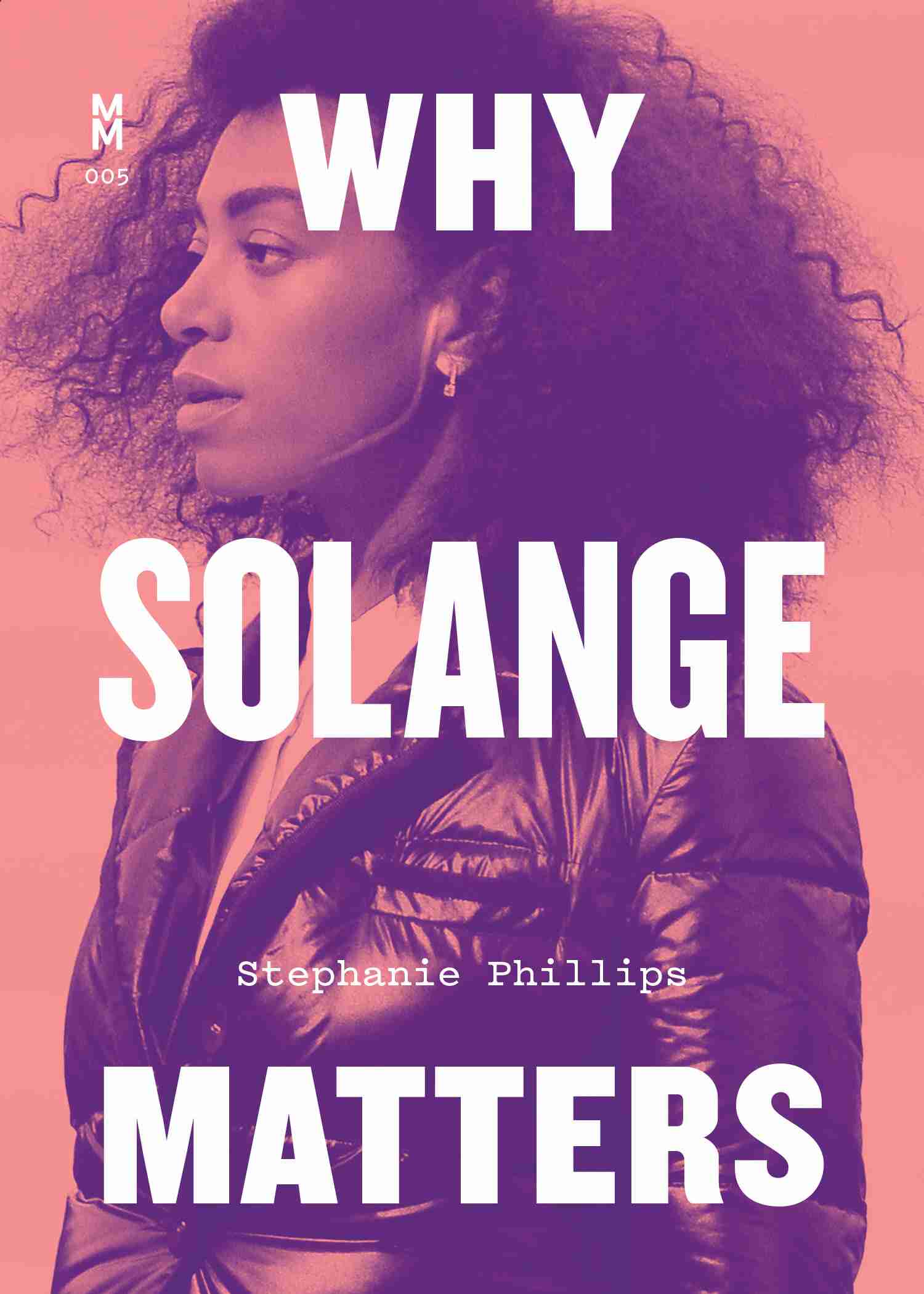

With that, I was recently wowed by Why Solange Matters, which came out last year from University of Texas Press under its Music Matters umbrella. The book was written by Stephanie Phillips, a Birmingham-based journalist and 1/3 of the Black feminist punk band Big Joanie. (They’re embarking on a European tour later this month, including some shows supporting Bikini Kill and St. Vincent, for those of you across the pond.) It’s a thorough and extensively researched look at Solange’s life and career, but it’s also grounded in Phillips’s own family history and “Black girl weirdo self,” as she puts it in the preface.

I knew pretty early in the book that I wanted to try and speak with her, so much so that I already had a page of questions by the time I finished it. We ultimately chatted this past week about the pressures of writing the first real book about a beloved pop star, said pop star’s era-defining (and oft-copied) visual stamp, and knowing what to do with what Phillips described as “the Beyoncé elephant in the room.” Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Where would you locate the beginning of your Solange journey?

Although I didn’t realize it at the time, the beginning of my Solange journey was when I was about 11 or 12. My family took me to see Destiny’s Child in Birmingham, which is the nearby city to where I lived in Wolverhampton in the UK, and we saw them at the arena there. It was around that time when Solange was touring with them in the UK and Europe and doing things like that. So I think that was my early introduction to her.

But other than that, I think it was probably through the Hadley St. album [2008’s Sol-Angel and the Hadley St. Dreams] and listening to “T.O.N.Y.” and songs like that. She was always someone that I knew about because of the family and because of her music, and slowly over the years, as more information came out about her and her approach to fashion and hair and different things like that, and exploring new musical avenues, I became more and more intrigued by her.

First of all, I’m very jealous that you got to see Destiny’s Child.

It was very fun!

I always like to ask authors how they went about chaptering their books and approaching the research, because your book is generally chronological but not interested in being a biography in the traditional sense.

When I first started the book, I laid out my ideas for it. And I think my editor suggested looking at a few other books that were on their roster—the book’s part of the Music Matters series from University of Texas Press—and the book Why Karen Carpenter Matters was quite interesting, quite influential, because that was a book that was about Karen Carpenter but more about the author’s personal relationship with her, and connections to family and heritage and history.

And so I thought that could be an interesting way of exploring an artist, because the idea of why Solange mattered was that Solange matters as a musician but more for how she represents this generation of Black people, and how Black millennials see themselves and view themselves changed over the last decade or so. I tried to structure it chronologically like you say, while weaving in different stories from my family that I thought could link in and make sense. From where it started out to where it is now, it changed quite a lot structurally. Which is a great thing about working with the editors I worked with. But it really took a lot of research… and Google Docs…

I can imagine.

…and putting up a lot of different quotes into Google Docs that would be relevant to different themes. It was a long slog of figuring out what the book could be or how to best showcase these ideas. But I thought it was better to focus a lot on A Seat at the Table (2016) because that was such an important album, so that album covers a number of chapters. And then there are themes within the chapters on mental health, Black women and being seen as angry and stereotypes in that way, and activism and Black Lives Matter. I tried to use each album and build out from that while relating it to what was going on at the time.

Did you imagine yourself as writing for anyone in particular?

The main thing was that I knew… it was about Solange, it wasn’t necessarily for Solange. I think that’s the hurdle you have to overcome when you’re writing these kinds of books. As much as I love her work, it wouldn’t be the book it was if it was specifically her view of how her career has been, or how she is as an artist or a person. It’s gotta be slightly removed from that.

But I guess I also wrote it for Solange fans as well as people that would want to know more about this period in history—her career has been about a 20-year period in music history—and using that kind of music and cultural criticism to relate it to a wider world.

When I emailed you, I said I appreciated that the book wasn’t stanny, so to speak. You’re clearly coming from a place of respect and admiration and even fandom, and are generous in all the right places, but you’re obviously uninterested in leaving certain conversations out. And I think that sort of thing instills more trust in a reader, at least a reader like me, as far as the rest of the book goes.

You’re not there to just repeat the same things that could be on Twitter, like a stan page. That’s the good thing about cultural criticism; it allows an artist or a band to be considered seriously. The whole idea of the book is that Solange is an artist who’s incredibly important to our time currently, and could be more important as she grows as an artist over these next few years. So if we’re saying that she’s as serious as she is, she needs to be properly considered and reviewed as an artist. And that means being honest.

Right.

I’m also aware that this is the first book on her. There hasn’t been a book on Solange before, or like an extended analysis on her work, so that also made me both insecure of what the future will bring in Solange cultural criticism—I’m sure there will be more books about her as the years go on—and also put a lot of pressure on to make sure that this book could be a solid basis for the first book on her. And then someone else can hopefully read it and add to my research.

These days, she’s associated with certain stylistic quirks and aesthetics, but maybe it’s fair to say that those same aesthetics—if we’re talking visually, at least—kind of only kicked in during the second half of her two-decade career. It does feel like there was a longer gestation period for her as an artist. I think it’s one that’s been really good for the work itself, but I mean in the sense that she’s really come into her own and made that indelible visual mark on everyone since maybe 2012, and then it solidifies around 2016. But before that, there was a lot of experimentation, and there wasn’t as much of a cohesive narrative that could be written about her.

There was a lot of figuring things out and really earnestly trying on new ways of being to see what fit her. I think she’s carried on some of those personalities and some of those quirks. It’s not obvious in A Seat at the Table and When I Get Home (2019) but it is there, in that detour away from the more cookie-cutter R&B that she started off doing. I think these last albums wouldn’t exist without the stop-off of the True (2012) EP era. So there are ways that she’s still incorporating the things she did in those early years. But they definitely don’t match up to this last decade, where she’s been so essential to the Black community and our sense of self, and also to music criticism and music in general.

One theme I picked up on in your book is that she’s often characterized as like… anything but a musician. She’ll be a little sister, a teen mom, a natural hair icon, an influencer—anything but a musician, which you push back on in the book.

That’s the impact of her changing the way that she’s always seemed in the media. She’d take on these different roles over the years. But then it obviously showed that her music wasn’t really being taken seriously, and as an artist you can imagine how that would have offended her. There’s still reason to take seriously the work that she was doing prior to A Seat at the Table. It wasn’t bad and it was still quite popular, it was just that she was the sister of a bigger pop star and not that big pop star herself. And that was always overshadowing her. It also felt like one of those things where people wanted her to lessen herself, have her be the beautiful model or the influencer, and have a visual with no point of view backing her up. And she always rebelled against that, and pushed for having her own voice and having her own say in things.

You sort of infuse her with this rebellious… punk sensibility is one way of putting it. Which I think she would appreciate.

I hope so. [Laughs]

When you embark on this kind of project, dealing with a subject who’s kind of been overshadowed by her older sister, do you have a plan in mind in terms of like… you’re gonna try and avoid saying her sister’s name? I know there are people out there who have very strong feelings about whether Beyoncé’s name should even come up in discussions of Solange’s work. Even prepping for this call, I was sort of like, Hmmm, will I get shit for asking about Beyoncé from people who read this?

Yeah, it’s difficult. At first, my thought was to try and avoid the Beyoncé question, avoid the Beyoncé elephant in the room. But realistically, to do a book like this, I had to look back on Solange’s childhood, and you can’t look back on her childhood without recognizing her parents’ history and how that impacted her, but also how it impacted Beyoncé. And how, when Solange was growing up, Beyoncé was more or less a local star by the time she was about 10 years old, so there’s no way to talk about Solange without talking about how she was always the one in the background since she was a small child, and how much that would have affected her.

And also, they do have a close relationship, they do talk about each other, they do seem to influence each other quite heavily. I spoke about that in the book in terms of how Solange writes for Beyoncé, and how she’s inspired her into working with different producers and stuff like that. So it’s about the way that you talk about it and bring it in context. And also, it’s part of her history, so there are lots of interviews I read when I was doing my research where you look back and the journalist would more or less say, “We wish Solange was Beyoncé.” There was always that hanging over her head, so you can’t really talk about Solange as an artist without talking honestly about how those references to Beyoncé would have affected her.

I think it also maybe factors into the way that Solange picks up different references as a teenager, and gets into different pockets of pop culture than her sister was operating in. I’m thinking about how she gets into Fiona Apple, for example. One of the things that was really fun for me reading the book was getting this education in her artistic taste that I didn’t have before.

Yeah, it’s a lot wider than you would think it was, and that was one of the interesting things researching the book, seeing how vast her influences were and what she was thinking about as a kid. And also how she’s still kept those influences going. She’s said that her favourite movie is The Wiz (1978) and Diana Ross is still an influence on her now. And I think that movie was quite a big influence on the When I Get Home era and film that she made. It’s also an interesting thing because you don’t really always hear about Black women and Black girls that listen to System of a Down and Fiona Apple who also really love Nas.

And seeing Solange in this way, doing proper research for the book, she wouldn’t have been that much different to any other Black girl her age. She was growing up in the era of MTV, she would have watched everything that was on TV, and there’s no way to say that she would only be listening to what the mainstream idea of Blackness would be listening to. She would listen to everything, and that was interesting for me because I was the same as well, listening to everything as a kid.

It’s interesting to think about how Solange is five years younger than Beyoncé is, so one kid gets the ‘80s MTV and the other kid gets the sort of grunge… it’s a very different MTV than the one Beyoncé would have been starting to develop memories in.

I also think it’s important to remember that Beyoncé didn’t have as much of a childhood as she maybe should have had. She was working from a very, very young age. That could have also influenced her music taste because if she’s training to be a pop star, there’s only a certain amount of music that she’s going to be told to mimic and listen to. I think that’s something that also influenced them both. Beyoncé just didn’t have the time—because she was working a lot of the time during her childhood—to explore more things than she was offered.

One of the more fascinating things to me about Solange is the way that she’s often characterized—I think falsely—as sort of anti-pop. Which I think I get, but it feels to me like you have to be actively ignoring many things there in order to reach that conclusion… about her work history, her influences, her taste, and so on. I mean, this conversation started with Solange being a backup dancer for Destiny’s Child.

She’s definitely not anti-pop. I’d still say that she’s a pop star because even though she’s using alternative and experimental influences in her music, it’s still to reach a more or less pop aesthetic. It’s still catchy and listenable and it’s not like she’s recording a washing machine and using that as a soundtrack to her music. [Laughs] Also, so many of her influences are pop… Kate Bush, Aaliyah, Diana Ross, so many R&B singers. Brandy is one of her big influences. I think she’s just showing a different way to be pop, really, rather than in opposition to it. It’s more widening that definition and widening that spectrum of how Black women can engage with popular music and present themselves.

She gets used often by people on the way to make their anti-Beyoncé arguments, which I think does such a disservice to her own work. I remember there being tweets when it was announced that When I Get Home was going to be on Criterion Channel, since that wasn’t too long after Black Is King (2020) came out on Disney+. And people were like, Oh, that perfectly summarizes the two sisters and their differences, and one’s authenticity and one’s inauthenticity. But it feels like people are very heavily invested in this distinction that the sisters themselves have never courted.

It’s interesting because it doesn’t seem entirely correct. There’s a lot to suggest that Beyoncé is courting the Criterion Channel as well, trying to make these very intense, in-depth feature films.

Absolutely.

There’s a lot of that in Lemonade (2016) or previously the BEYONCÉ (2013) album. Those videos that wouldn’t be that out of step in that independent art world. It’s just published and promoted by one of the biggest pop stars in the world right now. Solange and Beyoncé are not that different; they’re two sides of the same pop coin, I’d say. Because they’re slightly different, people view them as extremes when they’re not. Solange isn’t this out-there experimental artist and Beyoncé isn’t this cookie-cutter pop star, really.

They’re often on similar wavelengths, too, like in 2016 their work was obviously very much in conversation. You could make an argument that it was in 2019 as well, with When I Get Home and HOMECOMING where they’re both name-checking the same HBCU—Prairie View, I think it is.

Yeah.

Could you talk a little bit about the arts hub that Solange founded in 2013?

Saint Heron started off as a label where she could release a compilation [2013’s Saint Heron] and promote the artists she likes. I think she helped promote Kelela and Sampha and different artists like that—more alternative R&B, as it was called back in 2013, 2014. It’s more just R&B now. Over the years, it’s morphed into an editorial site, and then an online store selling and catering to designers that Solange liked, and now it’s more of an overall… it’s kind of doing everything. It’s a creative agency, it hosts exhibitions online. It’s an interesting way to go about things because she doesn’t necessarily have to keep it going, and it did go quiet for quite a long time as well.

Last year, she started to do press about it in a way that made it sound like maybe it was going to be resuming in a more solid way. It’ll be interesting to see how it continues to evolve. Hopefully I word this right because my intention isn’t to downplay her authorship or anything along those lines... when it comes to the sort of signature, more recent Solange images, the ones you’d have in your mind if I said that, they’ve often come out of collaborations between Solange and Alan Ferguson while they were still together. They co-directed “Cranes in the Sky” (2016), “Don’t Touch My Hair” (2016), and then he also produced the When I Get Home film. And then the chapter before that had been very defined by Melina Matsoukas’s style. So I’ve been wondering since Solange and her ex-husband separated if we might see that in whatever she does next, like a change of creative direction by default of the pretty big change in her personal life.

I think there’s definitely scope for that to happen depending on who she starts working with next. I can’t remember the last video I saw; I think it was an advert but it was in a similar style and aesthetic, but maybe a bit more experimental. It was her playing with this free-form jazz band. Her style might go more towards an experimental route.

The Alan Ferguson, A Seat at the Table aesthetic was amazing at the time, but over the years it’s been so copied by so many different artists. Every artist that you see now that wants to promote themselves as this kind of like… Black Lives Matter-type political artist... has the shot with all the women of colour around them, and has some sort of dance scene, and is dressed in all this fabulous clothing. And it looks cool, it’s just been so overly done and it’s very clear that Solange was the influence for that whole genre now of music video. So I think that she’ll definitely move away from that.

Something I find interesting as someone who follows both sisters quite closely is that they both favour this very collaborative approach to making art, like looping other creatives in and even swapping and recommending collaborators like you said earlier… Melina Matsoukas, Caroline Polachek. Beyoncé will co-direct things with other people and then credit them, but that approach gets used to downplay her artistic contributions, whereas the response to Solange collaborating with lots of people the same way is typically still like, Wow, what a singular artistic vision. Do you know what I mean?

That way of working is from the pop world. You have this writing room and try to come up with an album. Which is the way that both Beyoncé and Solange learned to be in the industry, and that’s why they still do it that way. But just with a slight detour in aesthetic and sound, it changes its meaning to the public at large. And I guess that’s because pop still isn’t taken that seriously, sadly, and there’s a lot of derision about the genre as a whole. But there’s not that much difference between the two, it’s just that Solange is getting a few more experimental musicians than Beyoncé is into the writing room. But it’s still a writing room.

Is there a project of hers that you think more people should seek out?

Two things. From the Hadley St. album, “Sandcastle Disco” is an amazing song and I don’t think people listen to it enough. It’s a perfect pop gem. And also, the True EP was really a lot more interesting than it was given credit for at the time. Journalists reviewing the album seemed to find it derivative, maybe, because it was very heavily referencing specific producers from the ‘80s, but listening to it now, it feels like there’s a lot of weight in those songs and a lot that you can still take from them.

You’re obviously a musician yourself, and something I loved about the book and would describe as one of its main differentiators is that you actually get how that world works… the business itself, the craft, maybe even things like the particular tolls that it can take on a performer, which feels relevant in Solange’s case. The first thing I did after finishing the book was listen to your “Cranes in the Sky” cover, and then I ended up listening to pretty much everything of Big Joanie’s on Tidal. I do find that a lot of cultural criticism sometimes lacks that fluency in the actual business side, but it really helps make your book.

At first, I wasn’t sure about adding in much of my voice, but I think it was my editors that suggested to add more of my story. I think it was the right choice because it gave a musician’s perspective on what Solange was going through, but also showed how a lot of Black musicians were going through similar things at the same time, and coming to the same conclusions as Solange was… starting their own organizations at a similar time as Solange started Saint Heron, doing things that were more about centering Blackness and understanding herself. Similar things were happening in the UK and the US. Lots of Black and brown punk festivals and shows were starting up in the alternative scene. I think it gave a bit more insight into that. I don’t think I needed to be a musician to write the book, but I think having that experience gave me a different perspective.

I think it definitely did. I’m actually chronically ill, and when Solange revealed herself to be living with this sort of nebulous illness, it unlocked this new dimension of her work for me. Obviously she’s not seeking these things out for exactly the same reasons as I am, but I deeply respect how much disappearing and recuperating and reorienting she does, and how she makes that a very central part of her persona, because it doesn’t feel like it’s necessarily the norm across the industry.

And it really should be because everyone needs rest and everyone needs time to themselves. I don’t think artists owe us that much at all... anything at all. It’s amazing to get the work that people do give out, and when social media started, at first it was nice to hear from people you wouldn’t usually hear from, but now I don’t really want to hear their opinions. [Laughs] I like someone that’s happy in their life and well-rested and stays away from social media and paparazzi and stuff like that, and then comes back whenever they’re ready.

I love a good logged-off celebrity.

Absolutely. ●

Mononym Mythology is a music video culture newsletter by me, Sydney Urbanek, where I write about mostly pop stars and their (visual) antics. I do that for free, so if you happened to get something out of this instalment, you’re more than welcome to buy me a coffee. The best way to support my work otherwise is by sharing it. Here’s where you can say hello, here’s where you can subscribe, and you can also find me on Twitter and Instagram.