Hannah Strong Talks Sofia Coppola as Student and Steward of Art

One of the more fun and rewarding things I’ve ever gotten to work on was this piece last year on Sofia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette (2006), a film that’s meant a lot to me since I first saw it in theatres with my family, and that I argued in my essay is the centrepiece of Coppola’s MTV-inflected career. While there are lots of people who make movies who’ve also dabbled in music videos at some point, Coppola is a bit different from her peers in that her dabbling has also included starring in them, whether that was in Madonna’s “Deeper and Deeper” (1992) or the Chemical Brothers’ “Elektrobank” (1997). Also unlike many of those other filmmakers, Coppola has never really left that world behind, from the actual style and content of her features to the fact that she still makes the odd music video proper here and there—most recently Phoenix’s “Chloroform” (2013), which I’ve shouted out in this newsletter before.

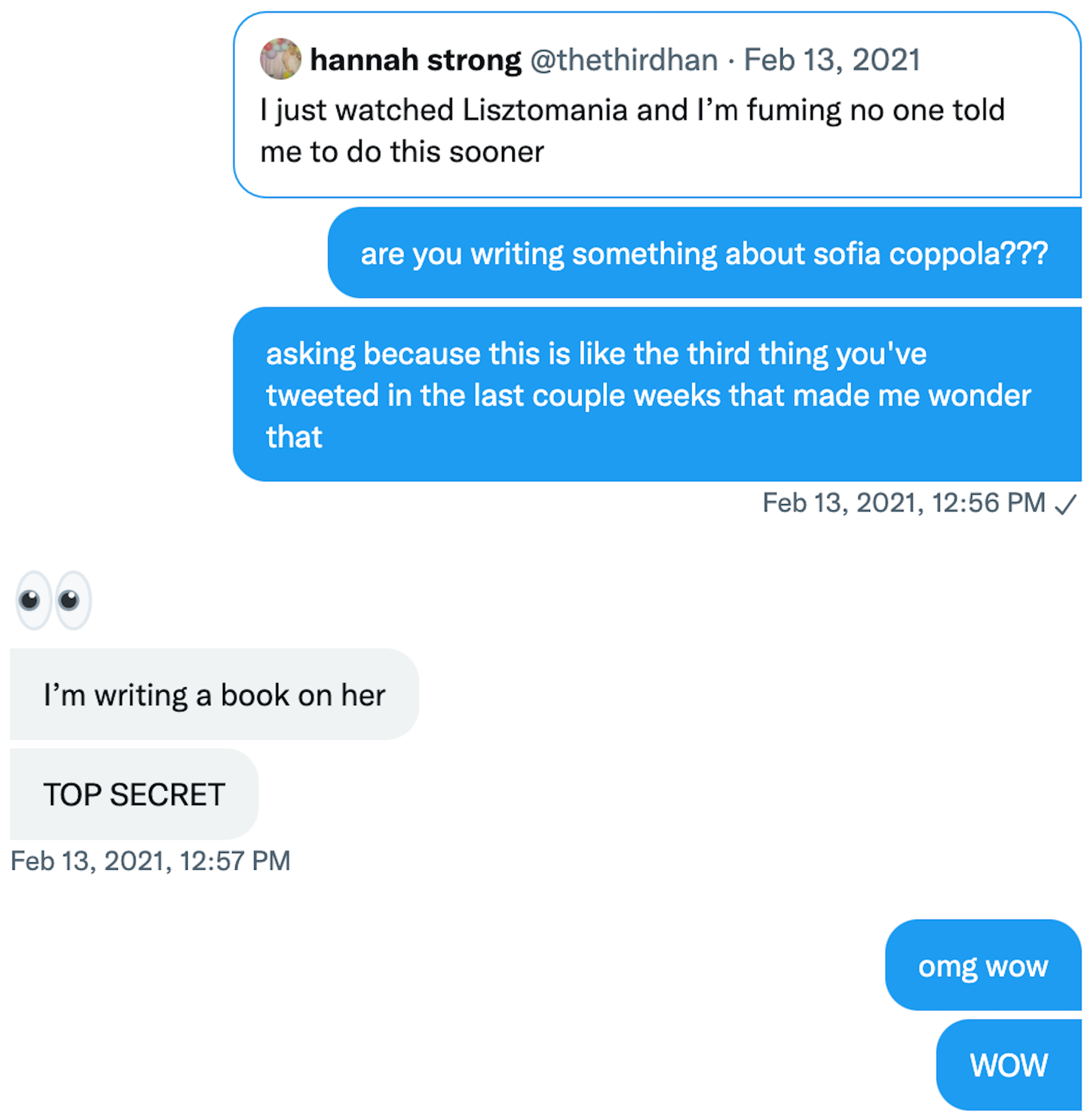

Somewhere in the midst of my Marie Antoinette research, which had been leading me to reference points all over the second half of the 20th century (and not so much the 18th, which you’ll understand if you’ve seen the film), I started to notice that my long-time internet friend and sometimes editor, Hannah Strong, kept tweeting about a lot of the same reference points. Most of these could be chalked up to cultural popularity or coincidence or even just the fact that it was Hannah, a known Sofia-head; around the same time, I’d actually consulted something that she’d written about The Virgin Suicides (1999) as part of my research for my essay. But then, one day:

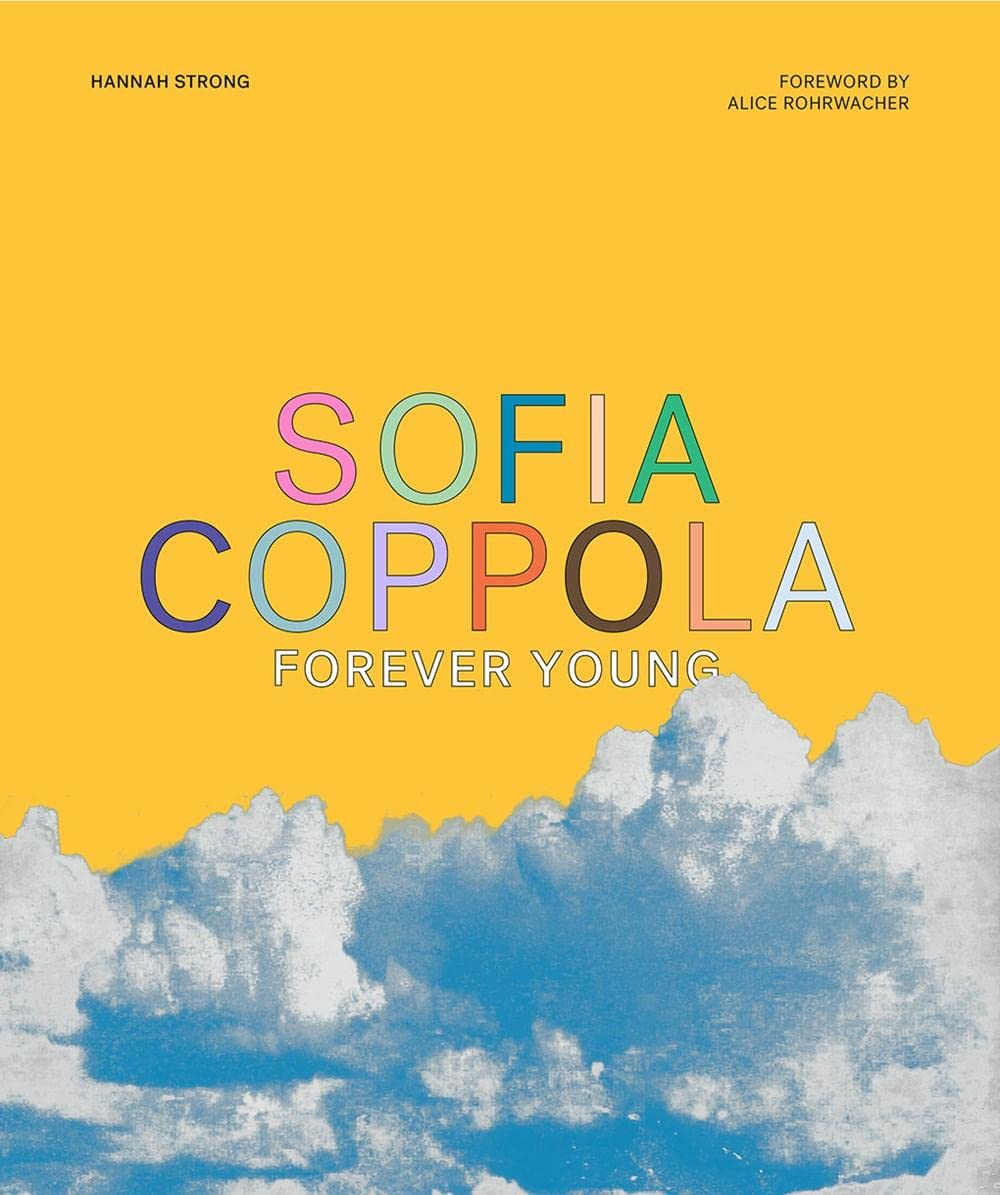

Almost a year and a half later, a lot of which was spent having to do the impossible (at least for me) of not spilling Hannah’s beans, Sofia Coppola: Forever Young is finally out from Abrams Books. It’s an awe-inspiringly good retrospective of Coppola’s career—not a surprise by any means coming from Hannah, but definitely good news given that we first made plans to chat about it six or so months ago—and certainly the most beautiful book I’ve flipped through in some time. Below is my quote unquote interview with her, which really felt much more like two Sofia Coppola fans shooting the shit for an hour over Zoom. We got into everything from our shared awful writing habits, to the horned-up terror that is being a teenage girl, to what Hannah described as the “amazing element of discovery baked into” Coppola’s films. Our conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Maybe for starters, tell me about the day that Sofia Coppola enters your life.

I don’t remember the exact day; there are a lot of things I don’t remember from being a teenager. And I think some of that is I’m getting older, and some of it is—as you may know, and I’m sure other people will know—when you have traumatic experiences, there’s this fight-or-flight thing where your memory just blocks stuff out. I had a really difficult adolescence, and was very, very unhappy for much of it. So there’s lots of things that I just don’t remember, especially with film. I wish I could be one of those people who’s like, “I remember the first time I watched a Martin Scorsese film” or “...the first time I watched Pulp Fiction (1994),” but I just don’t. I know I watched these films but I have no idea when or how it happened.

It’s the same with Sofia Coppola, but I do remember that I watched The Virgin Suicides. I remember being 16 and feeling constantly like the world was ending. And then I watched this film, and it was one of the first times I’d seen the unhappiness that I felt internally expressed through another medium. I’d seen Girl, Interrupted (1999) at that point, and I’d read some Sylvia Plath as many teenage girls do, but it was the first time I’d seen a film that I really connected with. And it felt almost like I was accessing some forbidden knowledge, but in a weirdly life-affirming way. It made me feel better knowing that these kinds of really horrible feelings I’d experienced were not as unique and terrible as I thought they were.

You do something interesting in the book, and I think very smart and admirable, which is throw us right into the emotional tumult of your teen years. This is a dead-horse topic on my end, but I really like when writers admit to there being a personal history behind a particular obsession. I’m sure there are exceptions but I find that you don’t really tend to become an expert in something without that something having gotten under your skin somehow. And I find it weird when writers pretend that they just woke up interested in Tudor history one day, and that that’s what’s been propelling their 50-year Anne Boleyn obsession. Do you know what I mean? It feels very dishonest.

[Laughs] Yeah, absolutely. And there’s this weird thing in pop culture criticism where people want to pretend that you can be very objective. For me, the whole reason I enjoy reading criticism is I like getting into the person’s point of view, and I like acknowledging that their lived experience is valuable in some way. And the best criticism, the criticism I enjoy reading the most—and the writing I enjoy more generally—is stuff where I can feel a person sitting at a computer writing it, sitting with a typewriter, sitting with a pen and paper.

I remember reading this essay during lockdown, it was in the New Yorker I think, and it was a writer talking about having her dog put down. And it’s obviously a very emotional topic, but it felt like there was such an intimate connection between the writer and the reader. And that was something that I was very keen to foster. I also wanted to be very upfront about what this work means to me. And sometimes I worry that that can be emotionally manipulative. Putting too much of yourself into a piece can be a very daunting thing, and there have been some valid criticisms about the idea that female writers feel like they have to use their trauma as a way to get commissions.

But reading the book, I think it’s very clear what an impact these films had on me and what they mean to me personally. That was really the only way I could access the material and bring it to the kind of audience that it was going to get in a book form. It’s a much broader audience than you get writing for a website. And it also felt like it was maybe something I hadn’t seen in that type of critical form. The books that I read about film, unless they’re memoirs, they tend to be very… straight, and oftentimes a more academic exercise. And I’m very aware that I’m not an academic, and I wanted this to be the book that I would have loved to read when I was a teenage girl. I would have loved to feel like someone loved this as much as I did, that someone felt a similar way to me. So in a way, it’s a very selfish project.

I went back through our Twitter DMs to get a handle on the timeline. And I’d forgotten that I sleuthed out that you were writing something about Sofia Coppola, because I think you were deep in the Marie Antoinette portion of your research at the same time as I was for a different thing. And there’d been offhand tweets I’d seen that I was curious about, but then you one day tweeted something about Lisztomania (1975). Which is such a specific and curious reference, not even one of Ken Russell’s better-known films, so I was like, “Okay.”

[Laughs] “Hang on a second.”

And I’d recently watched it for the same reason myself, and you were basically forced to come clean to me that you were writing a book. And then I had to sit on that intel for like half a year.

You did really well! And in a way, it was kind of thrilling because it was like, “Sydney gets it. Sydney knows about Lisztomania.” Talking about the book with people that love Sofia Coppola, there is a kind of kindredness between us. I think because we’re so used to it thought of as this frivolous filmmaking, or being routinely dismissed, or her being criticized—and it’s not all without merit—there’s this camaraderie between this little community of Sofia scholars who understand that there’s a lot of meaning in the work. And things like Lisztomania, there’s probably no way I would have watched that had I not been writing this book.

Can you talk about where and how you start to approach a woman’s decades-long career, and maybe how the book is organized in the end? It reads like you started with the core body of work but then ventured outwards into these other pockets, like key Francis Ford Coppola films.

With the other books that Abrams have done, they’re always keen to try and present a filmmaker’s work in a way that makes sense to the author but is easily understood by readers. I remember Adam Nayman with the Paul Thomas Anderson films presenting them in the order in which they’re set, which I thought was a really novel way of structuring a book.

When it came to Sofia, because she has so many recurring themes throughout her work, I wanted to break it down into these subsections that represented those themes. She’s a director where her progression I don’t think has necessarily been a straight line; she’s had peaks and troughs with her films, and I liked the idea of being able to talk about something that comes a bit later in her career with something that comes quite early—The Virgin Suicides and The Beguiled (2017), or Somewhere (2010) and On the Rocks (2020). It just seemed like a fresher way of structuring the book. And I think it really fit in with this personality that I wanted to bring to it, this idea of someone guiding you through these films that you know, but in a way that helps you pick out new things within them.

But you’re completely right in terms of how the process worked. The first thing I did was rewatch all her films when I was doing the proposal. So then I was going, Here’s this film I know really well, I’m going to go away and watch all these films that Sofia has mentioned as having inspired her film, or that seem to have informed the film. And then at the end, I went back and did all the early-work chapters. I think I maybe would have benefitted from doing that first, but it’s my first book so there’s things you learn as you’re going. You’ll know from doing long-term research projects, you sometimes forget what you’ve written down. So when I was coming to the end of it, there was a lot of, Aw man, I’ve mentioned this twice.

It’s so different to writing a long article. Even in university, I never wrote anything more than 10,000 words, so I was totally overwhelmed at first by the idea of having to structure something so precisely, but also think about the way that someone was going to read it. I think that it’s definitely something all writers should get the chance to do at least once, because it teaches you a lot about yourself and your work ethic. And what I learned is that my work ethic is… it’s good, but I’m very much a ‘do it the day before it’s due’-type person.

I’m the same. I was going to ask what you’re like as an actual writer. Are you at a desk trying to hit a daily quota? It doesn’t sound like it. Up in the middle of the night with a pot of coffee? Listening to Vivaldi?

I’m gonna really tell on myself now, but one of my great to-my-shame things in my adult life has been never being one of those people who can just sit at a desk and meet a word count. And I’ve talked to people who’ve written books, and a friend of mine was writing his book at the same time as I was doing mine, and he was being very disciplined about reaching his daily word count, and I was just there like, I can’t relate, that’s just not how my little rodent brain works. It’s feast or famine; I either do 3,000 words in a sitting or I do 10 words and then get bored and have to go do something else. But I am a night owl; there’s just something I like more about writing when everyone else is asleep.

But you know how people talk about sleep hygiene, and this idea that if you have good sleep hygiene you’ll be a healthier person? I wonder if there is such a thing as writing hygiene, if I would be a more productive writer with better habits. I really wish I had a nice, neat desk and could be one of those people who’s really committed and can turn it on or off, but I struggle massively with that. I think it’s also down to my attention span, and that’s something that I’ve had to really work on throughout the process of writing the book. Once my brain started seeing it as an obsession more than a work task, I think it got a little bit easier.

I’m definitely the same in that I’m actually not an unorganized person—I’m a very organized person—but I can’t get my brain to cooperate with me when it comes to writing. One thing that I really liked about the book is that you include A Very Murray Christmas (2015) alongside the feature work; it has its own chapter. And that’s a very common omission in listing her features, I’ve noticed. That’s also something that comes back to the idea of music television and how it existed in the pre-MTV era. And I liked that you got into that history there of Christmas specials, where there’s only a handful of artists these days who keep those alive. I thought that was so weird in a good way, like a fun, weird one-off project in her filmography.

This is another reason why I like her so much as an artist; she has this very eclectic approach to the projects she takes on, from doing A Very Murray Christmas to directing a production of La Traviata to doing the film for the New York City Ballet. She’s always struck me as an artist who’s open to trying new things and doesn’t always succeed at those things. I’m very much of that mind as well, doing things like picking up a new hobby every week. That kind of curiosity appeals to me because I’m that sort of person. With something like A Very Murray Christmas, it taps into this form we don’t really see anymore, which is the musical variety special, specifically the musical Christmas variety special. But it also, as you mentioned, builds on this rich history within her career, being a filmmaker who really celebrates the connection between film and music.

And there’s something very DIY about A Very Murray Christmas. Obviously it’s in the Carlyle [Hotel] and it’s this very bougie version of DIY, but I love the idea of calling up friends and saying, “Hey, let’s go make this goofy Christmas movie together.” I’m always a sucker for a film where someone is clearly making something with their friends and enjoying it. I love it when Steven Soderbergh does it, I love it when Wes Anderson does it, and I love it when Sofia Coppola does it. I think that kind of fun behind the camera translates very easily into fun on camera in her films. Something like Marie Antoinette, you can just tell they had such a fun time making that film. And maybe that’s why so many people were so hard on it; they thought it wasn’t taking the subject matter seriously. But all I can think about is the amazing documentary footage that Eleanor Coppola shot where they all look like they’re having the best time. And I think it’s balancing that with the often very serious themes that Sofia is dealing with in her work. It makes my synapses fire.

Marie Antoinette and Amadeus (1984), which is my actual favourite movie, were both things that I either watched or was shown as a kid to learn something about Austria, because that’s where my family comes from. And so one big reason for my fondness towards Marie Antoinette is how it was inspired a few different ways by my favourite movie. And that’ll be partly why I count it as my favourite of Coppola’s, which I realize is not necessarily a popular opinion. That part of my brain just overrides any kind of technical or critical or cerebral observation I could make about the film.

I’m very much the same. My favourite is Somewhere, and again not necessarily a common pick among her filmography. I think the associations I have with that film are very positive, but there are also the connections to other art I love. It may not be the film that other people think is her best work, or that I necessarily think is her strongest technical work. I do think it’s her strongest screenplay, which is very funny because it’s a tiny screenplay and there’s not a lot of dialogue.

But yeah, this is the other thing I love about her. No matter how many conversations I have about her work, people will have a very different justification for why their answer is the answer it is. And you get that with a lot of filmmakers, but it feels to me like with Sofia, people who love her work do have these very personal relationships with it. And that to me… it’s why we’re here, man. It’s why I do the job I do. I think that movies have really enabled me to understand myself better and understand the world around me better. So hearing that people have a personal connection with a movie and what that connection is—whether it’s something like parents trying to instill you with culture, or whether this film had meaning for you at a time where you didn’t find a lot of meaning in the rest of the world—is incredibly valuable, and I think why I wanted to become a critic in the first place. I wanted to be part of that world that seemed, to me, a place for human connection.

Absolutely. So because you said that, another big thing for me with Marie Antoinette is that it came out the year I turned 10, which was roughly the same age that Sofia Coppola was when Adam Ant was experiencing his cultural peak, because I think she’s born in 1971. So the two of us, Sofia Coppola and myself, we’re alike in that we love a good dandified man. There’s Ant… I know Prince is another one that she’s named as a formative reference… I think she and Harry Styles would probably get along. But with that essay that I wrote, I never say it explicitly in the piece but part of what I’m writing around is the fact that like… me finding the “Stand and Deliver” video on the internet—which I would never have done were it not for Coppola and Marie Antoinette, but especially her continuing to mention Ant in those DVD special features—played this massive role in… I don’t want to say my sexual brain, but I think maybe that’s what I mean.

I think it’s interesting that we are kind of in this moment where people are talking a lot, seemingly more than ever, about desire on screen and what it means to make erotic films and whatnot. And I think with Sofia, there are hints at sex but that’s not what her films are about. But female sexual desire, and in particular sexual awakening, is present in her work. And she treats it in a very sensitive way, without it being a kind of, This is a big political statement I’m trying to make about teenage girls. And I think I’ve always appreciated that the women in her films, the agency they have and the desires they have are treated with a sort of… it just goes without saying. I don’t want to shit on Booksmart (2019), but you know when Booksmart came out—and I enjoyed Booksmart—it was a whole thing about like, I’m doing it for the girls. What I was seeing in Coppola’s films was a kind of acceptance of these feelings of lust and having a crush and romance. And I think she maybe doesn’t get credited enough with that side of her. It’s not something that I got into really in the book. With another year of discourse behind me, I probably would have.

The other thing is, and you kind of touched on this a minute ago with the “Stand and Deliver” video, one of the great joys of doing work on Sofia Coppola is that you discover so much. She’s got this great kind of generosity; she doesn’t pretend that she isn’t inspired by other films and books and music, and she’s very open about those influences. I feel like I’ve discovered so much amazing work through a) watching her films, and b) watching her talk about the things she loves. As a filmmaker, when you see her interviewed, I think she doesn’t particularly like talking about her own work, but she’s always so ready to talk about someone else’s work. And so articulate about why she loves what she loves. And as someone who’s such a maximalist—I’m like a cultural hoarder, I love discovering new things, and I love recommendations—it feels to me like she’s constantly feeding me this string of amazing artists. I went and saw the Ed Ruscha exhibition in London because of watching The Bling Ring (2013) and seeing that painting. It feels to me like this amazing element of discovery baked into all of her films. I always come out of one with a new micro-obsession within the wider obsession with her work and the worlds she creates.

She almost takes on a curatorial role in that sense. That’s sort of what she’s doing is repurposing her favourite things, maybe. As you already know, I’m very fascinated by her ‘90s work and ongoing music-world adjacency, whether that’s the handful of videos she’s made, the handful of videos she’s starred in. People reading this newsletter tend to be interested in Madonna, obviously. But then also Sonic Youth, which is a huge pivot from that… the Chemical Brothers, also very different… Hi Octane technically falls under the MTV umbrella by way of being a Comedy Central show.

With Hi Octane, there wasn’t a lot of mention of that before maybe a few years ago.

I definitely learned about it through Charles [Bramesco], who I think wrote about it a couple years back.

I think it was Charles for me as well.

I feel like it might have something to do with YouTube, and the fact that someone just uploaded a bunch of episodes one day.

It’s interesting to me, that show. It’s become like a discoverable artifact again through the medium of YouTube. I feel like it would do well now, like if it turned up as a YouTube filmmaker doing it. There is this kind of How to with John Wilson irreverence to it that I think is very ‘90s and in keeping with that kind of… irony poisoning. When you watch that show, you can really pick out all the things that inform her later work, and I think it really is so good to see her very clearly having fun, because I think there’s this element in criticism around her work, positive and negative, where everything seems very meticulous and very choreographed. Hi Octane does have this kind of anarchic feeling to it. I wish I’d had room to go longer on that because I think it’s a fascinating bit of popular history. I’d love to talk to Zoe Cassavetes and some of the other people involved in that.

It comes back to the curatorial thing where like… she’s the spectator as much as she’s the filmmaker, she’s sort of enjoying anything alongside the audience. One of the interesting manifestations of that, I think, is the way that characters in her films are always watching music. Like Stephen Dorff lying in bed watching these two twins pole-dance is sort of like me lying on my couch watching Kate Moss pole-dance in that White Stripes video. Maybe that’s sort of a galaxy-brain example of that but you know what I mean. Something she does a lot is let songs play in full, and not just in the montage sense like with “I Want Candy,” but also the figure skating scene in Somewhere, or the “My Hero” scene. It’s interesting because people don’t really do that for the most part.

People don’t let music go on in films. That’s something you have to be pretty confident as a filmmaker to do. But I also think you’re onto something there. I’d love to read an essay about watching and being watched in Sofia Coppola movies. I think it also speaks to her as a filmmaker because she’s someone who talks a lot about how many films she watches. During lockdown, she was talking about watching films with her family, and she’s someone that does engage with art in a way that I don’t always get the sense some filmmakers do. She seems to have this appreciation for other artists, not just filmmakers but also musicians and fine artists. She seems like someone that I think is good at engaging with art. And I think her characters oftentimes are pretty good at engaging with art, too, whether it’s high art like Marie Antoinette at the opera, or the low art of watching a stripper in your bedroom.

You can’t really call it a use of silence, but a lack of dialogue is so interesting to me in films because you can infer so much from what a filmmaker is not… it’s like that quote about the notes you’re not playing saying as much as the notes you are. My favourite example is the end of Somewhere, like there’s a good however many minutes where you’re just in the car with Johnny Marco, and it goes on for such a long time, and you’re just there with your thoughts basically. And I’ve had loads of conversations about the end of that film and what it actually means. Is this guy okay? Is he gonna be okay? Giving the audience time to think and time to reflect is such an underrated thing in filmmaking, particularly contemporary filmmaking. But she’s a filmmaker who I think really does make space for her audience to have those self-revelations.

Her most recent couple of features are in some ways the quietest that she’s made, not packed full of needle drops the way some of her other work is. They’re not music-free, but music is used very differently in them. With The Beguiled, it feels like at the beginning she turns the gas on, and the whole time you’re waiting for the thing that’s gonna like… ignite everything. And there’s a really interesting way that the sound design parallels that.

That’s such a perfect way of describing that film. It’s easily her tensest film; you’re on edge the entire time, and I think the sound does contribute a lot to that. It would be so easy to put some kind of discordant Jonny Greenwood-esque score over the top of it. But I think that the silence makes it even more foreboding, especially when you think about the place where the film is set and the time it’s set, and this idea that you are just sitting around waiting for something to happen. A lot of the film is the girls sitting around waiting for something to happen.

On the Rocks is a really interesting one because the time it came out has meant that people haven’t really talked about it as much as they would normally with a Sofia Coppola release. It kind of came and went without much fanfare. But it’s a very sad film, it’s a film about realizing your parents aren’t as great as you thought they were. And realizing that marriage is incredibly hard work; I came out of the film not particularly feeling like I want to ever get married. [Laughs] But the stillness that you can find in a city like New York, which is so intense and so crazy, and there kind of isn’t any silence in New York... we get that a little bit in the film, but it’s really interesting to me that she’s chosen one of the busiest cities in the world but made it feel very melancholy and very grey, very isolated.

In a way, that’s an interesting contrast from how Tokyo feels in Lost in Translation (2003). That city in that film feels very vibrant; the busyness is a welcome distraction. And although the film does have a lot of melancholy in it, the city feels overwhelming in a good way, whereas in [On the Rocks] it’s kind of the opposite. That busyness is oppressive. And a lot of that is to do with what the film’s about, the dying days of capitalism—which I’m sure is not what she intended to confront; it’s my takeaway. I would have loved to speak to that sound designer. I obviously talk to Brian Reitzell, who’s amazing and such a generous interview subject. But I do think it’s a really interesting and kind of untapped part of what makes her films feel the way they do. Because people are so obsessed with how beautiful the films are, which they are, maybe it doesn’t seem as obvious.

Reitzell is sort of a fascinating figure to me in that he’s credited usually as music supervisor when his role is more expansive than that—non-traditional might be a good way of putting it. Maybe you could talk a bit about him and the role that he plays in her films.

He was up there with Kirsten [Dunst] for me as someone I really wanted to talk to, because they’ve been working together since the beginning. He was there on The Virgin Suicides and he was instrumental in shaping that soundtrack, which is so iconic even beyond Sofia fans. His role, like you say, is a lot more expansive than a traditional music supervisor. There’s the obvious thing of him having worked on the tracks from the films; he worked on a track with Oneohtrix Point Never for The Bling Ring, and I believe he was playing something on the score for The Virgin Suicides. So he’s a professional musician and comes from that world; there’s the practicality of it.

But also, he’s very good at finding music that speaks to Sofia’s worlds that she’s trying to create, and he talks about the mixtapes they’ve made for every one of the films he’s worked on. We were saying that Sofia’s a curator in some ways, I think it’s a very similar role that Brian plays. But then there’s also the hustle aspect to it, and there are some great anecdotes in the interview about how they secured all these huge artists for The Virgin Suicides. Because he comes from that world primarily, there’s this authenticity that he brings to her films, and it’s an understanding of music and why you use a certain song somewhere.

I remember speaking to Paul Thomas Anderson, and he said something I found so funny about when you’re choosing music for a film and you feel like you have to put a song in there because you got the rights to it. He made reference to this satirical headline, “‘Cherry Bomb’ Played in Lieu of Actual Female Character Development.” That’s something you don’t ever really get in Sofia Coppola films, the sense that songs replace character development.

It’s never forced.

There’s this element of looking for those deeper cuts and deploying music in a way that feels interesting and meaningful, rather than just as a kind of, Oh, we can’t have any dead air. I think a lot of films are afraid to have silence. It feels to me like [Reitzell] has a very good understanding of Sofia’s taste, but also her artistic sensibilities, and then has the kind of connections within the industry so that people like the Cure will feel like their music is in safe hands. Because they trust that Brian and Sofia are going to be these good stewards for those songs.

You mentioned earlier that you think Somewhere is probably your favourite feature. Do you have a personal fave among her short-form work?

I have a real soft spot for Lick the Star (1998). Stylistically and technically, it’s very rough around the edges, but it really gets to the heart, I think, of being in high school, being in middle school. And I think it’s a really clear early indication of her sense of humour, and just this way she has of writing. Which does feel quite stylized but also very true to human experience. I just think it’s a really fun little sign of what was to come; I think you can definitely see these preoccupations she had as a young filmmaker with the kind of intricacies of female relationships, and with obsession. I love the fickleness of high school girls and that they’re obsessed with this “Lick the star” phrase one day, and the next day it’s Flowers in the Attic. It’s very funny and has this little dark edge to it that I think you oftentimes see peeking in a little in her work.

She’s always coming back to certain threads that she may have started a long time ago. This is sort of different but I remember being very moved reading that quote from Jason Schwartzmann where he said that until Amadeus, he didn’t really know that people from history laughed. Because you don’t think about that kind of thing when you’re a kid. And I think he said that totally separate to that quote where Sofia explained that Amadeus is why the accents in Marie Antoinette were the way they were, so it makes you wonder whether they watched it together as cousins growing up.

There’s an element of cultural exchange within the Coppola family that makes Sofia’s work incredibly rich. There’s a lovely quote from Eleanor Coppola’s diaries about watching Sofia on the set of Marie Antoinette, and she’s explaining to Rose Byrne and Asia Argento and Kirsten Dunst about the scene in the hallway where Marie Antoinette snubs [Madame] du Barry, and she says, “Okay, I want you to imagine it’s like The Outsiders (1983).” And I thought that was such a lovely bit of Coppola intertextuality, but also the idea that she talks in film references is very charming to me, and again speaks to this idea that she’s a film-lover first and a filmmaker second. ●

Mononym Mythology is a music video culture newsletter by me, Sydney Urbanek, where I write about mostly pop stars and their (visual) antics. I do that for free, so if you happened to get something out of this instalment, you’re more than welcome to buy me a coffee. The best way to support my work otherwise is by sharing it. Here’s where you can say hello, here’s where you can subscribe, and you can also find me on Twitter and Instagram.