Adam Nayman Talks David Fincher’s Adman Past (And Present)

A little over a year ago, I published an instalment of this newsletter (then still in its Substack era) called “What Happened Between Madonna and David Fincher?” It was about how two creative visionaries, both of whom I have a great deal of respect for—contrary to what their publicists surely believe—and whose work I’ve enjoyed for years (Fincher’s for many more than Madonna's), had a serious and very much romantic affair that was more or less hidden in plain sight. When the two first met to collaborate on her video for “Express Yourself” (1989), Fincher was only 26—the wunderkind of the production company he’d helped to found, Propaganda Films—and while he wasn’t yet David Fincher the three-time Oscar-nominated filmmaker, he’d already made quite a name for himself directing short-form work. Some of that was commercials, like this one for the American Cancer Society; a lot more of it was music videos, where his clients already included people like Rick Springfield, Sting, and Paula Abdul. By 1991, he was officially the most-nominated director ever at the MTV Video Music Awards (VMAs), a title he still holds three decades later.

I knew that my piece was on the juicier side. I didn’t by any means expect tens of thousands of people to read it, nor fans of both parties to debate my claims on message boards, nor a bunch of people to write in helpfully alerting me to evidence that I’d missed. And I sure as hell didn’t expect for it to be cited in a real, actual book coming out later this month, Adam Nayman’s David Fincher: Mind Games. Adam is a fellow film critic and the author of several books about films and filmmakers, including but not limited to The Coen Brothers: This Book Really Ties the Films Together (2018) and Paul Thomas Anderson: Masterworks (2020). (Though we’ve never crossed paths in person, he also teaches in the department where I did my Master’s program.) He opens Mind Games with a dedicated discussion of the decade or so before Fincher ever made his narrative feature debut with ALIEN³ (1992), but then continues to come back to his commercial and music video work for the remainder of it, wisely treating his adman past as, well, more of an adman present. A few weeks back, Adam and I chatted for an hour about Fincher’s short-form oeuvre, but also his features because—again—the two aren’t as discrete as a lot of people believe. Our conversation has been edited for clarity, but not really so much for length.

Congrats on making it to this moment because not too long ago, I remember you describing Fincher to me as a “tough nut to crack”—was that the phrase?

Well, a tough nut to crack… he’s kind of a titanium-coated filmmaker, right? And I think that you end up in the position talking about this filmmaker with friends, long before I was gonna write this book. Do you bother trying to penetrate or pierce the films, or do you just admire how hard and metallic and reflective those surfaces are, and leave them at that? I think that the discourse around Fincher is either, There’s nothing underneath, so what’s the point? Or, conversely, that it can be hard to crack through to the point—not because the movies are necessarily obscure, but because there are so many layers of technique and certainty and intention in the way that he makes movies. Breaking through that… even to say something original is not easy.

He obviously isn’t the first nut that you’ve ever had to crack, so to speak, because you’ve written multiple books now about various quote unquote auteurs. But what was different about this particular project, and this particular nut?

I’m trying to think of how we can use nut and legume analogies for all these filmmakers. I think with the Coens, if we’re gonna take these books as a weird, very circumstantial trilogy... and maybe not unfortunately, but maybe a bit dubiously, they’re kind of a broteur trilogy. I don’t think of myself as a doctrinaire film-bro guy, but the Coens, Anderson, and Fincher… they’re maybe not the top three dorm-room poster filmmakers for dudes of a certain age, but they’re in the ballpark. And in each book, you have to acknowledge that popularity and that appeal that the movies have, and also try not to limit it at that.

So with the Coens, my challenge was trying to not just be like Chris Farley on the Chris Farley Show and be like, Remember in The Big Lebowski (1998) when that happens and it’s funny? Because my admiration for those films is total. So it’s trying to mitigate total admiration, and not just paraphrase the movies—I love them—but try and say something about interconnectivity. In that book, I found that watching Coen Brothers movies often feels like being trapped in these self-contained loops, and to a larger extent their filmography is a loop, where you have… in Raising Arizona (1987), the joke that H.I. McDunnough—the Cage character—is a recidivist, he keeps committing the same crime over and over again, which seemed to me an interesting analogy for auteurism. The Coens are trapped in loops, but their movies are also very spacious, and they open up. So that book is all about the difference between being trapped in the interpretive loops that the Coens create, and trying to break out of them and connect these movies to the larger world and history. I had a lot of circles in mind when I wrote that book.

And then with Anderson, who’s a filmmaker for whom my admiration is not total… my admiration is very real, and sometimes I would say it’s even a kind of love for the movies he makes. Even a very unlovable movie like The Master (2012) makes my heart skip a beat; I think it’s phenomenal. But I also had to honour the 20-year-old version of myself back in 1999 who was like, These movies are bad and I don’t like them. Not because I was immature but because I found them so imitative and so show-off-y. And I was getting into so much other world cinema in my early 20s, and Anderson seemed pretty expendable to me. And then the way that his moviemaking changed suddenly made him seem really important. So that book was all about trying to separate out the myth of Anderson as the young tyro who becomes a master, which is so easy, and make it more about the history of California and Los Angeles and America—a psychic history of America—which is where I think he’s become a brilliant filmmaker. Like, I don’t think Boogie Nights (1997) is a brilliant commentary on the ‘70s; it’s an amazing piece of filmmaking, but it’s almost shallow as history. I think Inherent Vice (2014) is way less accessible than Boogie Nights, but there’s lots going on. Even if it’s taken from Pynchon, there’s lots of hindsight that’s pretty... funky.

So with Fincher, for whom my admiration is... uneven, and who I find hard to love, sometimes hard to like because… when he’s good, he’s cold and grotesque and off-putting and smarmy. And I’m trying to find a way in, and I thought that a couple of ways in were through the past and advertising, which I think manifests in different and interesting ways in so many of the movies. And the interest in messaging, and the extent to which his movies are a critique of mass media and mass communication. But it also struck me in writing about the movies that he doesn’t make the same movie over and over again, he has these clusters that he returns to. There are these procedural films, there are these non-official prison films—these labyrinth movies or these maze movies with people navigating confined spaces—there are these movies about the nature of reality.

As he’s gotten older, he’s started making movies about the nature of time and the nature of truth, which is why I think his two His & Hers movies—his romantic comedies, I guess—The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (2011) and Gone Girl (2014), are both very funny, because they’re sort of about not just the contest and the arena of emotion and romance and sex, but about contrasting views of reality. In Dragon Tattoo, it’s analogue and digital, but in Gone Girl, it really is, Who puts the best face to the world? So I guess image maintenance struck me as something that’s interesting about his movies as well. The structures of the Coen and the PTA books came very naturally; here, I feel I had to labour—hopefully I haven’t laboured too hard—to break these movies into groups. And that’s just to keep it from being a strict, left-to-right, “here’s what happened” recap of his work. Because that’s very common, I think.

And often less interesting. To come back to what you said about image maintenance and his interest in messaging, maybe you could explain what Propaganda was, and how Fincher landed there in the first place.

Propaganda is a name so good in retrospect for Fincher’s career arc that you feel like you’d have to invent it. This high-end music video house with really Bauhaus-industrial aesthetics… in L.A., but set apart from the main drag of studios and music video shops… with this very insurgent attitude, where it’s like, We’re gonna be an incubator, or a breeding ground, or a testing ground… a Fight Club (1999)-style space monkeys training facility for these music video directors. And what was interesting was, there was more of an association with Propaganda around artful-ness than artistry, or artisanship than artistry. Which isn’t to say that they didn’t house artists—they did, and the bare minimum you could say about Fincher is that he’s an artist; when people say he’s just a technician, I think they’re being really glib and dismissive—but Fincher described it like a jukebox. You put your money in one end, and your video comes out at the other.

So, this dovetailed with incredible changes around the economy of music videos, and the economy of the music industry. It was expensive but cost-effective for these big artists to make big, expensive music videos—to use the big, new promotional vehicle of MTV. So that’s what was interesting about calling it Propaganda. What does propaganda look like when there isn’t a coherent ideology behind it, or is the ideology here just, Sell each artist on his or her own terms? And they did not start with top 40 or top 10 artists; they were on the fringes of the top 40 because they were very emergent and new. And there were a bunch of music video directors there, who you’re obviously familiar with, who were part of that stable.

But Fincher pretty early on had the juice. He had the ability for a middling pop act or a middling rock act to create something striking enough that you wanted to give the song another chance. And for an act that was already catchy and that was already getting radio play, he gave them a real foot in the door of the TV arena. There were huge, important music videos made long before Propaganda—you know as well as I do that there were huge, important music videos made long before the official launch of MTV. But relatively speaking, we’re talking about the ground floor. And we’re talking about a barely suppressed ambition to bridge from music videos into movies, by making music videos quote unquote cinematic.

And I mean, we can flash-forward to the VMAs in ‘89 where Fincher is three out of five nominees for Best Direction, and then the next year it’s even sillier where he’s three out of four nominees. The VMAs don’t hold the same weight these days, but I was looking this morning at various winners and nominees, and it takes until directors like Hype Williams and Jonas Åkerlund in the late ‘90s for that to start happening again, where directors are doing so well that they’re competing against themselves. But it’s never quite again as extreme once Fincher more or less leaves the industry to make features.

No, and to stick with that idea of ‘89 there… you’ve got him making videos in that period like “Freedom ‘90” (1990), this George Michael pop ballad. You have Madonna, who’s maybe not that generically distinct from George Michael, but it is a different sound, a different voice, a very different kind of icon. But then you’ve got Don Henley, who is not pop; Don Henley is at that point adult contemporary rock, and ripping off Bruce Springsteen. But [Fincher] is also doing Aerosmith, which is hard rock, and he’s doing Paula Abdul, which is dance-pop. And this is where you get that admiration for his flexibility as a technician, and as a conceptualist, to do videos that suit all these artists.

But then you’re also like, Where’s the there there? If you’re just taking gigs and taking paycheques, this is a very gun-for-hire thing. And if you contrast the very cloistered, under-the-radar world of music video auteurs with, say, Hollywood auteurs, Fincher was seen as simultaneously an award magnet, top-of-the-industry superstar, but also pretty promiscuous. What unites these videos? It’s not a liking of one style of music. He works with the same artists over and over again, which is maybe a kind of loyalty, or it’s just a steady gig. I think that there wasn’t that much music video criticism being written at the time, but if there was, people would have wondered, So what’s the deal here? Is he flexible? Is he adaptable? Is he a really mercurial talent who can go from thing to thing? Or is the common denominator just that they’ll pay him?

Reading the introduction to your book, I kept jotting down descriptors that all felt like they were part of the same thought bubble—precise, obsessive, exacting, and so on. A big through-line in the book is the idea of control, and the average fan of his features might not realize how much of that reputation, how much of his style and even his thematic preoccupations, predated ALIEN³. But in your view, in the greater David Fincher story, how big of a piece is his music video and commercial work?

I think it’s a huge piece because it alone—cumulatively, but alone—explains why he gets ALIEN³. Ridley Scott was a David Fincher type in the late ‘70s, but there was less riding on Alien (1979). It was expensive, and it was a post-Star Wars movie for Fox—no one should pretend like the first Alien came out of nowhere—but it was not a global franchise already; it was an effort to make a good standalone horror movie. And when it came time to make Aliens (1986), they put the call out to James Cameron, who also wasn’t James Cameron yet. He had made a hit like The Terminator (1984). When it came time to sequelize a giant franchise like Indiana Jones, their first call was Steven Spielberg, and they don’t have a second call. Lucas only farmed the Star Wars movies out because he wanted to; that was his choice to evacuate directorial responsibility.

So for a 27-year-old to be hired to direct ALIEN³, unless he’s someone’s son, which he isn’t in industry terms, there has to be an incredible set of calling cards. It’s so weird to make the link between Madonna and Alien because that’s either like a bad punchline or a complete non sequitur... it’s kind of naming two iconic pop female icons. But without the Madonna videos, he doesn’t have the schlep and the reputation to even be looked at for the Alien films. If he’s looked at for those films, I think it’s because someone sees behind Madonna in those videos, or behind some of those other stars in those videos… there’s an aesthetic that’s transferrable to a sci-fi universe one way or the other. And that’s where you get into the fun thing of analyzing images and themes and actually seeing that “Express Yourself” and ALIEN³ are twins.

But just in terms of industry power, that’s what getting three MTV nominations in one year does for you. The whole history of Hollywood is the history of wanting to either fight off other mediums or absorb them. So that’s what [Pauline] Kael wrote about in the ‘60s when she said that Hollywood is afraid of television, so it’s trying to compete with TV—not just by having TV directors do movies, like all the Playhouse 90 directors like Lumet and Altman, but by hiring advertisers. It’s hiring people like Richard Lester, who directed commercials, to make movies. Kael thought that that had a really bad effect on movies aesthetically, but by the ‘80s, she must have really wanted to blow her brains out, because then it’s not What’s Richard Lester doing to movies? It’s What’s Russell Mulcahy doing to movies? What’s Tony Scott doing to movies? What’s David Fincher doing to movies?

Obviously there was a two-way street in the sense that these music videos were often also referencing films. One of the reasons that I’m drawn to Madonna in the first place is the very conspicuous engagement with film history, and it was fun for me to realize that all of the Fincher collaborations—with no exceptions—are grounded in at least one very specific, very patent film reference. Sometimes something from the classical Hollywood period or even before then, like Metropolis (1927), but just as often something that in the context of the late ‘80s or early ‘90s would have been a more contemporaneous reference, like Wings of Desire (1987). But it was a two-way street in the sense that the ‘80s completely changed how films looked and sounded, and in the book you mention Body Double (1984) being one of the more unsubtle examples there. It’s not that the film and music worlds had been separate prior to the ‘80s by any means, but they get tangled in a sort of unprecedented way, and I think maybe permanent way.

I think in a very permanent way. Just to look at Bruce Springsteen, for instance, who’s probably on or close to that same music video level of dominance as a Madonna or Michael Jackson—while being less flamboyant or overbearing than either, since Springsteen’s persona has a root centre of like, the humble conscience of American liberalism. Which doesn’t mean costumes; he doesn’t play werewolves and stuff. But Springsteen in the same year has videos being made for him by Brian De Palma, who’s one of the most florid, flamboyant technicians of the New Hollywood. Then he has videos being made for him by John Sayles, who’s kind of the Bruce Springsteen of cinema, except not popular. Sayles is a really principled, serious, left-liberal, and now it’s like, you don’t just have music video specialists, you have these major American filmmakers taking the opportunity to work in music video. You have John Landis doing it, you have Scorsese doing it for Michael Jackson with “Bad” (1987).

So what you say about there being a back-and-forth, it’s even truer than that; it’s a multidirectional give-and-take. I mean, Madonna’s genius—among other things—is obviously this subsuming and synthesizing of pop culture. Something like “Vogue” (1990) is amazing as a song because it pays due reverence to the icons of the past, introduces them to young people who wouldn’t know them, but the ultimate point is still that Madonna belongs and is almost above them for uniting them together. I’m not meaning that like she’s arrogant, it’s just an incredible thing: Here are all these people whose names I’m gonna rhyme off. I’m the one rhyming them off. I belong, and they have all led to me.

But of course, arrogance is not an unwarranted descriptor here; I think that’s maybe her appeal, and maybe even Fincher’s appeal, for a lot of people.

For sure, and she didn’t do that right away. If you look at—and this is pre-Fincher now, but you love this stuff, so I like talking to you about it—videos for “Borderline” (1984) and “Holiday” (1983), those are videos that are sort of like, Here I am, I’m a pop star. “Like a Virgin” (1984) is an aesthetic, but it’s still just a showcase for her. By the time she does “Material Girl” (1985), it’s like, Hey, remember Marilyn Monroe? Well, here I am and we both played with her images—and, ergo, I am kind of Marilyn Monroe now. Not just in terms of doing her get-up or whatever but, I am an icon on this level. It’s an amazing thing that she did that. But if she’d done that with her first video, I think she would have been laughed off of MTV, or would have just been seen as playing dress-up. By the time she does “Material Girl,” fair enough for her to play with that iconography because she’s a gigantic friggin’ star.

She sort of gets into the film history stuff and never looks back, and I don’t think has ever really looked back. But to come back to Fincher, if you’re looking for them there are tons of parallels to find between the music videos and the features. Not just stylistically but sometimes even in terms of subject matter, like specific tricks that he’s testing out—I’m thinking of the opening and closing shots in “Freedom ‘90”—and references that he’d return to, like Citizen Kane (1941). But all of that said, you’re very clear in the book about how, prioritized above any of his own quirks was the artist in question, or whoever the client happened to be. He never at the end of the day seemed to forget that he was a hired gun of sorts.

He didn’t, and it’s interesting because he wants to be the hired gun, but he also wants to have control that in the Wellesian tradition or a certain kind of auteur tradition, has to do with a fully independent artistic vision; the control is commensurate with the level of invention. And I’m not saying Fincher didn’t invent for his videos—he did; a lot of those videos are not literal treatments of song lyrics. Some are. But the tension was between, You’re being hired to execute in service of an artist’s vision and Okay, so then let me do it. And that’s why the Madonna collaborations are so fascinating: there is an interesting power struggle anytime a strong director works with a celebrity musician. And I’m amazed, given the level of self-possession and image-maintaining brilliance that Madonna displayed prior to, during, and subsequent to that—with missteps—that she would sort of say for a two-year period, Whatever you want, David. Now, also while saying, Whatever we want, and being very active.

But the way she talked about David, she’s like Trilby talking about Svengali, right? She’s very mesmerized by this idea of working with him, at least in terms of her public statements. She handed that image over to him for a little while to drive with it, or for them to drive with it together. That’s a pretty significant chapter of pop history, I don’t think because David Fincher is an all-time significant pop figure—he’s a pretty important American filmmaker—but Madonna is gigantic. This period where she really peaked commercially and expressively is imbricated with him forever.

For sure, and I think one of the things it comes back to is that when you really break it down, he’s not as masturbatory a filmmaker as some people like to think.

No, I agree.

Something I really like about your book is that you lead with the music video discussion. It could have been an appendix, which would have painted all of that work as an afterthought. And while having the commercial work up front of course makes sense in terms of chronology, there’s a line early on where you describe his story as being one about “how an adman transitions into an artist (or if he ever really transforms at all).” Could you talk about that a bit?

That circles back to the slight anxiousness in taking the book on. Not anxiety because you’re worried people won’t care—his films have very strong fanbases—and not even an anxiety that there’s nothing to write about. But whatever else you say about the Coens, even if it’s a synthesis or… what’s the line from I Think You Should Leave? Even if they’re putting out a cosmic gumbo, they’re artists. And Anderson is personal and idiosyncratic, almost to a fault.

With Fincher, you do have that question of, Did an adman become an artist or did he just become an increasingly artful adman? There are very few movies of his where the guard gets let down, and I think it’s very telling that the two movies where the artistry is worn on his sleeves are The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (2008) and Mank (2020), which in strange ways are hugely garlanded by prestige-granting institutions. 10 Oscar nominations for Benjamin Button, same number for Mank. Great box-office for Benjamin Button; it was a hit. Not really great box-office for Mank because it’s during a pandemic and on Netflix, so we can’t tell.

And yet, those are the two films that put people’s teeth on edge a little bit. I find it really interesting that the recent announcement that he’s making The Killer with Michael Fassbender has been met with these sighs of relief online, where people are like, Thank God he’s making pulp drek again. Because for a lot of people, it’s pulpy genre stuff that unlocks his artistry; it doesn’t muffle his artistry. And something like Mank, which is more personal, which is more sentimental, which in some ways is arty—even though I think aesthetically it’s very much in line with a lot of his other movies—for some people there was a grasping it, or a reaching in it, that rubbed them the wrong way. And I think that you can interpret that—same with the people who found Benjamin Button sentimental—as subtext not so much that he’s a bad artist, but that he isn’t one. Because if he were an artist, rather than an artisan or a technician or a control freak or a pulp master or whatever, those movies wouldn’t seem so forced and cloying and separate from the rest of what he does.

I don’t think that that’s actually true at all with Benjamin Button, and not only do I think that that’s the work of an artist, I think it’s very clearly the work of the same filmmaker who made Zodiac (2007) and The Social Network (2010), and I talk about that in the book. I think with Mank, you maybe have more of a case that… it’s the first time he makes a movie with his heart on his sleeve, and the lack of ruthlessness betrays him a bit.

There’s sort of a tension between art and commerce in his career, which you mirror in having the commercial work keep popping up again in your discussions of his films.

Yeah, and I mean he’s kept making commercials, and sometimes the commercials are a testing ground for either technology and special effects, but also for attitude. Whether he’s making Nike commercials or Super Bowl commercials, you have these motormouth messiah rants by celebrities or by actors impersonating celebrities, and you see test runs for the kind of character Brad Pitt plays in Fight Club, and all those movies.

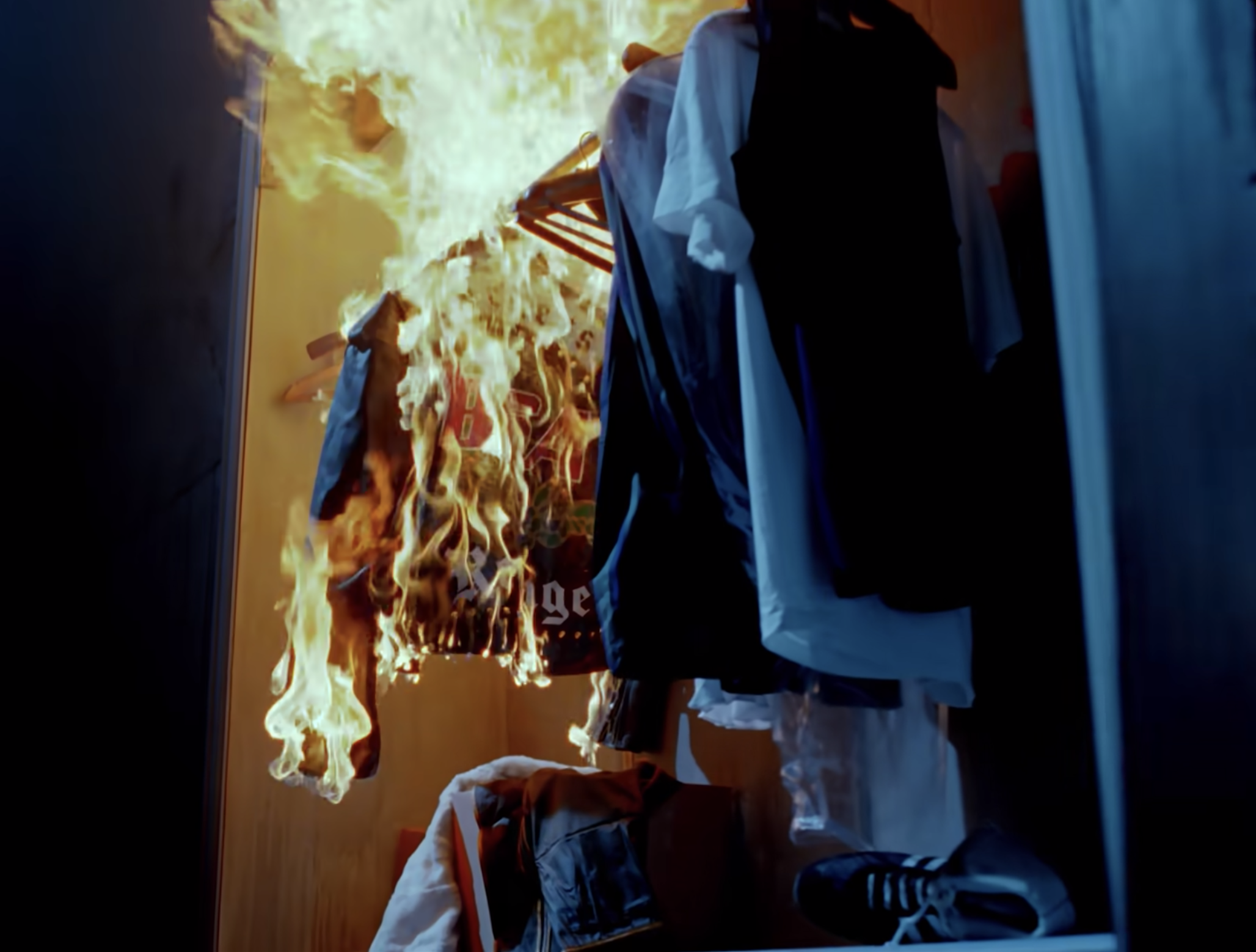

And Fight Club is a movie that I think is the single most interesting flipside expression of his adman history. Fight Club is a movie that imagines, in a Godardian way, the galaxy in a Starbucks cup. It’s a Godard reference but banalized by referring to Starbucks. It’s a movie that’s all about franchising and marketing and uniformity and conformity—and, again, it’s essentially a movie that’s filled with recruiting pitches, right? It has that very signature moment for him where Edward Norton’s condo becomes a catalogue, which is such a wonderful use of graphics, and such a wonderful way of remapping on-screen space.

And I think I say in the intro somewhere that for the people who like Fincher, he’s the guy who blows up condos, and for people who’re dubious about him, his movies are condos; they’re branded. But it’s not an artistic signature, it’s more of like a barcode or a seal or something. I think his commercial work pops up a lot in his movies—as test runs, as thematic anticipation. And even in terms of the actors he works with, I love that video he did with Brad Pitt that kind of remakes A Hard Day’s Night (1964), but instead of the Beatles it’s Brad Pitt, where he’s being chased around. The fact that I can’t remember what it’s selling…

It’s a beer ad.

And in some ways, the fact that I can’t remember what it’s selling would seem to be a criticism of its effectiveness, but I think it’s what Fincher is going for. Sometimes the aesthetic would overwhelm the product; the catchphrase or the conceit or the gist of the ad was bigger and more memorable than what it was selling.

I think Fincher can be one of the sneakier filmmakers in terms of you being able to see his music video or commercial background coming through in his features. But then occasionally he’ll do something like the Enya needle drop in Dragon Tattoo, or something equally bonkers where he obviously understands better than a lot of people how you can use a popular song to get under someone’s skin. It’s all about indelibility and irony, and then there are one-off moments that I find interesting. Even the opening sequence of Dragon Tattoo feels like the full-length version of this one set-up in Madonna’s “Fever” video from ‘93, where she’s painted silver.

It’s funny you’ve fixated on Dragon Tattoo as this pop inventory because in my chapter I describe it as his greatest hits album. It’s a movie that plays Fincher’s hits, and whether that’s out of disinterest for the material… I don’t think he thinks he’s above the material, but I think a lot of people thought the material was below him, or below anybody. That movie was a real breaking point for some people after The Social Network because whatever Social Network fabricates or invents or simplifies, it’s obviously a very smart, literate piece of work, and people were like, God, Dragon Tattoo, I mean why? And I think that, in a way, there’s so much plot and so much space in that story that he’s able to use it as a way to do his stuff. And I find that him doing his stuff is what makes the movie enjoyable… that Enya needle drop… that title sequence, which is like an audition for a James Bond movie that he’s never gonna make… he uses Rooney Mara to remind us of The Social Network, where she’s the foil to the tech savant, and then has her give a very tweaked but similar performance to what [Jesse] Eisenberg had done in Social Network, that idea of introversion—the kind of introversion that’s a by-product of technological advancement.

It’s kind of a movie about digital overtaking analogue, which is what Social Network is about. He restages serial killer stuff from Se7en (1995), he has a sort of May-December romance like in Benjamin Button. And again, it’s not the idea of him or anyone sitting with a checklist, it’s just that by the time he makes Dragon Tattoo, he has enough movies that he can pick and choose amongst his own work. I think it’s interesting that Gone Girl, which is much better material... he doesn’t have to pull out his greatest hits because he’s got a pretty good, smart, compelling, pitch-black satirical script to work from. I guess what was strange about Mank is that he’s trying to play somebody else’s hits to some extent. He’s trying to do a Wellesian aesthetic in a movie that has very misplaced skepticism and contempt about the Welles myth. One of these movies where it’s controlled but feels out of control.

Dragon Tattoo, whatever else you would say about it, even if you don’t think he redeems how stupid the Stieg Larsson material is, the film has shape and pace and intention to it. Rewatching it a couple of times for the book, I was amazed by the sense of convergence in it, like every set-up leads to the next set-up, and every editing choice leads to the sense of convergence, where it’s two and a half hours long but it feels so fluid. That’s the late-Fincher thing that I think is amazing is how, even in these epically long movies with endless set-ups, it’s not extraneous; it’s incredibly tight.

And some of that is removing certain plot points to make it a little bit neater from the original text. But I guess it’s true that whereas with Gone Girl, the irony is there already in the source material, he’s manually injected it for the most part into Dragon Tattoo through things like costume design and perhaps soundtrack. I’m thinking of the one shirt that Lisbeth wears in the one scene…

The “FUCK YOU YOU FUCKING FUCK”?

That’s what it is.

It’s very funny and again clashes in an interesting way with how he would use Rooney Mara in these fashion campaigns. Except, at the end of Dragon Tattoo, in the same way that the opening is like an audition for a Bond movie, the ending is almost like he’s playing Dress-Up Spy Barbie with her.

For sure.

I try to write in the book about how, what’s wonderful about those sequences is not the way that they advance the plot, but the way the character is constantly shown in between personas. She’s in the hotel room and you see the blond wig but you see the black roots underneath, and she’s got a white bra under a leather vest, and there’s this dress-up game she’s playing, which she has tremendous contempt for. She doesn’t want to be “Harriet Fucking Vanger,” as she says. She doesn’t want to be that person, but she’s not super comfortable or happy being herself, either. So that identity play loops all the way back around to Madonna, right? And to that malleability of persona—even if I don’t think Rooney Mara is an icon who’s Madonna-sized, he definitely uses her in a Madonna-ish or Lady Gaga-ish way in Dragon Tattoo, when the movie finally gets plot out of the way.

I think it would be dishonest for me to not admit at this point in our chat that that’s for whatever reason one of my favourite films of his—in terms of rewatchability, in terms of how I can get lost in it. I was also a fan of the books, which might help. But it is fascinating how, after all the twists and turns that it takes, we somehow end up at like… romantic drama.

Yeah, and I was just thinking about this in regards to Dune, where there will be a sequel, the best thing that ever happened to Dragon Tattoo is that they didn’t commission two sequels with Fincher. Not just because it’s freed him up to not get trapped in a franchise, but because of the irresolution of that ending and the way that what it reinforces is that character’s loneliness and toughness and independence, and also her fundamental yearning that’s not gonna be fixed. I haven’t read the subsequent books, but I know that there’s just acres and acres more plot, and more happens between them, and to her, and to him. And I’m sure for fans of the series—and I’m not belittling it—that’s very satisfying. But the fact that this movie cuts off and feels unfinished makes it unusual by Hollywood standards, and I think that’s very potent.

I think it could have been a disaster on a few different fronts, but one of them would have been that, as you said, he would have been tied up, and we wouldn’t have gotten something like Gone Girl or anything he’s done more recently with Netflix. Maybe we can put Mank aside.

Not to avoid Mank… it’s also the kind of movie that he has to make and it’s good that he makes, because this is what happens at a certain point; you get far enough into your career that these ideas of aging and mortality—and in Mank’s case, posterity, which is how I framed it thematically in the book—it makes sense that that would be on his mind. One thing I would say about Mank in its favour, because it’s not a movie that I hate and I try to make a decent case for what’s good about it in the book, it’s not a retreat move. It’s a movie he wanted to make when he was much younger, but for him to make it now, it’s not a retreat or a lack of ideas; it’s sort of a challenge to himself to say, I put off making this for 30 years, am I finally mature enough to take it on? There’s a smugness to some aspects of the movie that I think makes some people wish it wasn’t made, but I think there’s a certain riskiness to it and an openheartedness to it that I appreciate because it’s so fully a movie about his dad. And that’s not an overly ambitious, intricate reading; it’s in the movie and in the text of the interviews that he’s done about it. So it’s hard to begrudge somebody a gesture like that.

Last time we chatted, this was when you made the “Oh Father” (1989) joke that had nothing to do with Madonna.

And when he makes “Oh Father,” you don’t have Welles scholars coming out of the woodwork and saying, “How dare you?” Citizen Kane is part of the popular vocabulary and lexicon, so when you’re quoting Citizen Kane, whether you’re Fincher or Animaniacs or the Simpsons, it’s fair game. But when you’re making a movie that’s quoting Citizen Kane but also quite literally about how it was made, and who made it, and who deserves the credit for it, and a movie that has less-than-due reverence for Welles—which I’m of two minds about because I think that Welles is a protean enough talent to take it... but that doesn’t mean that what it says about him is insightful. Just because you can afford to make a movie that doesn’t heroize Orson Welles doesn’t mean that Fincher’s particular way of dramatizing him was great.

The book is broken up by these “Influences” inserts where you run through some of the existing texts that inspired each film. What would you say are the constants in terms of where Fincher seems to have pulled things from?

I worry about those sections because sometimes what those sections reveal is more the critic’s frame of reference or the critic’s desire for connectivity than what the filmmaker actually [intended], but I think when you look at the list Fincher has made over the years—not too many, but when he’s been pressed to say what the great films are—he’s in a really squarely limited pocket of the New Hollywood. But not even the outliers of the New Hollywood... not even your Hal Ashbys or your Melvin Van Peebleses. He likes Scorsese, and he likes Alan Pakula, and he obviously, given his early background in special effects, reveres Spielberg and Ridley Scott... he likes Coppola. He’s a filmmaker who came of age watching movies by people who were themselves coming of age as auteurs. And this is a longer discussion, but I try to get at it in both the Anderson and Fincher books, which is that auteurism is a fluid idea, too—not just as critical practice but as filmmaking practice.

The filmmakers who set out now are practicing an auteurism that’s like six, seven times removed from its original context. They’re trying to be heroic directors. Paul Thomas Anderson’s whole career is like, These guys in the ‘70s did it a certain way and I want to be like that because I see that most people aren’t. That’s not the original conception of auteurism, which is, you know, eking out the signature within the system. But I think that to use another music analogy, because Fincher doesn’t really write his scripts, that kind of singer-songwriter acclaim has never been his. And that singer-songwriter ambition has never been his. He wants to tell stories that are already there, stories that are brought to him, stories that are floating around looking for a director. He shapes every inch of the project, but the story doesn’t originate with him, and it puts him at odds a little bit with some of his generational peers, where the rhetoric is more like, Crack open Spike Jonze’s head and there’s a universe. Crack open Sofia Coppola’s head and there’s a universe. With Fincher, it’s like, you hire him and he looks at what you’re doing and he says, This is how we’re gonna do it.

He’s carrying out someone else’s treatment.

Yup. Except that, as he’s gone along, you follow the work and whether you like it or not, you see the ways that the films are personalized—and not just in like bespoke, monogrammed, superficial ways, but shaping the material so that the meaning changes. I don’t think that the script for Zodiac—and this is not meant as a shot at James Vanderbilt, because it’s a great script; I think it’s one of the greatest American movies, so I obviously think it’s well-written—had to result in one of the greatest films ever made in the United States. That’s [Fincher] bringing his stuff, including the reception around Se7en and his own ambivalence about how and why that movie made him famous. That’s where the juice of Zodiac really comes from. It’s very unique and specific to him. It’s a different way of saying personal... it’s maybe a less gooey way of saying personal. People are like, “Well, do you think he’s a personal filmmaker?” I don’t think he’s an impersonal filmmaker, so it’s a bit of a dodge, maybe. But I think the people who think that he’s just a gun for hire or just a technician are way off.

Tough nut to crack.

I guess so. I’d ask you, is there a film of his that you like for strange or unusual or very personal reasons? Is there a movie of his that you really like beyond the obvious constellation of favourites?

I didn’t realize until very recently that Dragon Tattoo is an unusual fave pick of his. And I think for me, there’s something about the mood. A lot of it is in the on-screen talent. Like, I know on an intellectual level that this is Daniel Craig, but by the 30-minute mark, it’s not. I’ve forgotten that these are not real people. And there have only been a handful of shows and movies in my life where I’ve had that happen, where the real-life part of my brain just totally shuts off.

[Fincher] can absolutely immerse you in the linear stakes and the linear development of a narrative; his procedurals are so watchable for that reason. Se7en is a movie that is constantly driving towards this vanishing point, and it’s amazing how as the vanishing point gets closer and closer, you still don’t see it—until suddenly it’s right there and you have this perfect structure locking into place. He’ll never make a more perfect structure than that, for people who see him as a pop structuralist, or for people who see him as a filmmaker who’s about that outer shape and that outer container and that outer frame. In some ways, he got it perfect almost the first time out. I think he’s been chasing the actual structural perfection of Se7en for a while. But then the reason Zodiac is an infinitely greater movie is because it’s not perfect—because it’s an exercise in irresolution, I guess.

I also really like the way that in Mindhunter, he has this handful of real people who have very strong reputations to anybody watching the show, but he’s dealing with a fictional world. I mean it’s real to an extent, but it’s this interesting mashup of real and not that shouldn’t work but somehow does. And again, he coheres it all into a very even project.

Tremendously even, and one that’s informed by a storytelling archetype that I think is very common in his work, and I point it out a lot even though he’s not known as this kind of filmmaker because he doesn’t do it the way that we see it in like, the American Pie movies or something, but Mindhunter’s very much coming-of-age. It’s a coming of professional age, it’s a coming of romantic and sexual age, it’s a reckoning with the dark parts of oneself. I didn’t want to stretch this too far, but there’s something of Kyle MacLachlan in Blue Velvet (1986) in Groff, this idea of a straight arrow getting bent out of shape through continued exposure to abnormal psychology. That desire to master abnormal psychology also means that you grow to relate to it, and I think that the writing in season one is very strong on that point, the way that he seems to take on some of these characteristics.

In a movie like Manhunter (1986) or in the novel Red Dragon (1981), Will Graham is tortured by his ability to identify and see things through serial killers’ eyes, which is very pulpy and great. But Mindhunter is a much more realistic treatment of what that residue does to you, especially when you’re not fully formed. It’s an interesting series about someone who wants to live in the realm of theory and then finds that a lot of other things get into your head. I had so many friends when Mindhunter came on at first dismiss it because it was so episodic and killer-of-the-week and whatever else, but I think when you look back on the two seasons, even with the creative struggles behind the scenes and some of the stuff that people haven’t wanted to talk about, it’s a very cohesive show. I agree with you that it’s even, and the character development on it—even by the standards of prestige TV—is very good.

Maybe as a final send-off question, what is a shorter-form project of Fincher’s that you’ve come to think of as required viewing?

I didn’t participate in this but The Ringer did a ranking of all the things that his name is on, and they didn’t differentiate between movies and commercials, and obviously the movies all rank very high because they’re substantial. I forget where they actually ranked “Freedom ‘90,” but it’s hard to think that he made anything better than that.

I don’t disagree. Even on a Madonna level, I’m between “Oh Father” and “Bad Girl” (1993)—I appreciate “Vogue” but it’s never done anything for me that’s been stronger than with those other two—but “Freedom ‘90” maybe trumps them for me.

It’s amazing how he manages in those six minutes to have… the women aren’t as individuated, they’re like a collective identity of professionally beautiful women, but each of them plays with the idea of their own commodification and their own beauty and their own presence in the music video, and Michael does the same thing by incinerating his past. And there’s this wonderful transference that is not winking or ironic or heavy-spirited… it’s this wonderful expression of freedom, of having the male voice come in and being lip-synced through the women.

At the lowest level, it’s the joy of pop songs; the pop singer becomes the ventriloquist for your own feelings, and you want to sing along. It’s How fun is it to sing along to this song? But then that feeling of emancipation goes in so many different directions. The women are singing through the male voice, the gay artist is liberated by lip-syncing through these beautiful women, and it’s unusual for Fincher… the organizing principle of the video is pleasure, and I think that in some of his movies, that pleasure becomes very masochistic or intermingled with a sense of threat.

I mean, the great scene in Gone Girl, the woman-on-top sex scene is so perverse because it’s a release and it’s cathartic and on some level the audience is very happy to see Neil Patrick Harris die because he’s a controlling asshole. She’s gonna kill him because she can’t kill her husband. But I wouldn’t call that uncontaminated pleasure; it’s very contaminated pleasure. The same way that in Se7en, you don’t actually want the cops to stop him. If the cops arrest him and stop him or he turns himself in 20 minutes before the end of the movie, you’re sitting there in the audience in a very cockblocked way. So it’s pleasure but it’s a very perverse kind of pleasure, but in “Freedom ‘90” there’s nothing perverse about it. It’s sexy and it’s kinky and it’s very pleasing, and there’s no bitterness in it.

There’s no ‘but,’ like it’s never tampered with at all.

No, and unless I’m missing something, he’s never really returned to that in the feature film work. There always has to be something complicating, there has to be something frustrating, there has to be some kind of wall to smash through. ●

Mononym Mythology is a music video culture newsletter by me, Sydney Urbanek. It’s totally free, but if you got something out of this instalment, consider buying me a coffee. The best way to support my work otherwise is by sharing it. You can subscribe here, and you can find me on Twitter and Instagram.