When MTV Lost the Upper Hand

This is the third of a three-part series tied to the 40th anniversary of MTV’s launch, in which I use things from the archives to delve into particular chapters in the network’s history. Last time, we got into the heyday of the TRL era. Before that, we talked about the very early, sometimes awkward days of the channel. Finally, we look back at the 2011 MTV Video Music Awards (VMAs).

I’ve so far been actively avoiding the topic of the VMAs so that I could devote this final instalment to them and only them, but the fact is that they’ve been happening in the background of everything I’ve covered so far.*

Launched in 1984, the show appeared just in time for Madonna to hump the stage during a performance of "Like a Virgin"—a month and a half before the song had actually come out. At the time, the VMAs were proudly and unambiguously about celebrating the music video format. Never have the VMAs not also been associated with debauchery and headline-making moments, but there was initially an understanding that MTV was simultaneously at the forefront of something artistically revolutionary. In 1984, all but one awards category had the word "Video" in it. Now, they're overwhelmingly called things like "Best Latin" and "Best Rock," where it's unclear whether we're really, truly talking about videos here at all.

The six categories currently known as the professional ones—Cinematography, Editing, Choreography, Direction, Art Direction, and Special Effects—have all been awarded since 1984. Today, these are the only VMAs categories not decided by fans voting on the MTV website; they're instead decided by a mystery group of industry professionals. (The whole set-up is altogether pretty shady, but it's nevertheless been the case since 2006.) Of those six categories, only Best Direction was presented during last year's broadcast, and presumably for ratings-related reasons: Billie Eilish and Taylor Swift, just two of the snowballing number of artists intent on self-directing their work lately, were both among the nominees. (I predict that we'll again see Best Direction televised this year, since five out of six nominees are artists who've self-directed their videos.)

Then, there's the matter of the Video Vanguard Award. Please allow me to quote something that I wrote almost exactly a year ago about the VMAs and how they work:

From 1984 to 2006, the award—called a number of different things during this time, including [but not limited to, it's worth noting] the Michael Jackson Video Vanguard Award—was given to a handful of directors *in addition to* artists who’d made waves in the music video world. In 1986, for instance, it went to Madonna *and* Polish director Zbigniew Rybczyński, even though the two had never worked together. After going to Hype Williams in 2006, the award went on a sort of hiatus until 2011, when it was presented to Britney Spears [...] with Michael Jackson’s name reinstated. With the exception of 2012, it’s been presented every year since then, and artists have taken to using the honour as an opportunity to perform medleys of their biggest hits.

The Vanguard Award wasn't presented during last year's broadcast. Instead, Lady Gaga was given the first-ever Tricon Award, which MTV said in a statement "recognizes a highly accomplished artist across three disciplines. This inaugural award is in recognition of her talents as a global music superstar, award-winning actor and undisputed fashion icon." But while Gaga fans—a group I count myself among, as you know—were quick to spread the news that an entirely new award had been created just for Mother Monster, my theory is that MTV had no idea what to do about the controversy re: the Vanguard Award still being named after Michael Jackson, and hoped that the Tricon would serve as a deflection. (Gaga almost certainly would have been one of the next Vanguard recipients, anyhow.) If MTV continues to hand out Tricon Awards in the coming years while saying nothing about the future of the Vanguard Award, assume that one has quietly been rebranded as the other—an ultimately easier route for the network, PR-wise, than having to make a big announcement about removing Jackson's name.

Either way, Gaga was a noteworthy recipient of such an award in that her career took off in 2008, the same year that OG TRL died. (The second closest thing would be Rihanna, the only Vanguard Award recipient to have debuted in a post-YouTube world.) In the first two decades of MTV, there was a symbiotic relationship between the channel and the music industry, but where MTV had the upper hand by miles; it could make or break your career purely by deciding whether to play something that you'd sent in. Over the course of the 2000s, however, things like Napster, social media, and YouTube became real problems for it—in terms of ratings, yes, but also in terms of cultural necessity. By this point, as in 2021, the original dynamic has been totally flipped: it's now MTV that's dependent on artists, and not the other way around. (Most write-ups of the 2020 VMAs paint Gaga, whom you could get away with calling a post-MTV artist, as having singlehandedly 'saved' the show.) But let's back up a bit to when said shift seems to have actually taken place.

*For the sake of length, I'm setting aside MTV's other long-running awards shows, like what are currently called the MTV Movie & TV Awards. They're generally speaking less culturally relevant and significantly less artistically important, even if they've had their moments. As Esther Zuckerman once wrote for the Atlantic, "The MTV Movie Awards don't matter, save for one category: Best Kiss."

My main artifact for this final part of my series is once again a live television taping, this time of the 2011 VMAs broadcast, which aired almost exactly a decade ago (on August 28). There are a number of reasons why I’ve chosen to revisit this show in particular, and I’d be lying if I said that nostalgia didn’t factor in at all. In 2011, I was smack in the middle of high school, and my friend and I both used to get dropped off at school weirdly early (anywhere between 45 and 120 minutes, depending on the day). She’d generally do whatever math homework of mine that I’d given up on the night before—she’s now a doctor, while I’m doing whatever this is—and then we’d fill the rest of the time with music videos, old and new, always discussing (and sometimes even reading about) what we saw.

We did this for most of high school, but 2011 was especially generous as far as new releases went—Adele’s 21, Gaga’s Born This Way, Britney's Femme Fatale, Beyoncé’s 4, quite a few singles from Katy Perry’s Teenage Dream (2010) as well as Nicki Minaj’s Pink Friday (2010), and so on. I don’t think that I’d realized until a lot more recently, especially as these projects have been turning 10, how formative the year had actually been for me.

But I promise that there are less romantic reasons, too. 2011 came at a sort of juncture between two eras, landscape-wise. In August of that year, Vevo—music labels’ answer to the streaming age—was now almost two years old. That means that we'd definitively crossed over into the era of YouTube being a monetizable thing, rather than a financially devastating thing, for the music industry. But while most big artists had been on Twitter for a couple of years, it would be eight months before Facebook bought Instagram, at which point everyone who's anyone joined the latter service. Put differently, the music industry had long ago surrendered to the internet, understanding that things like social media and free content were the future, but without the crucial piece that is the ‘gram. (This is as good a time as any to mention that MTV officially dropped the "Music Television" from its logo in 2010. The Hollywood Reporter figured that the network was better off without the "constant reminder that [it] was branding itself one way, programming itself another.")

The 2010 VMAs—perhaps most famous for Gaga’s meat dress—also happened during this same juncture, but I’ve gone for the following show because it was arguably more memorable overall, because aspects of the broadcast are nicely in conversation with my previous two instalments, and because there's a decent case to be made that it marked the end of a certain era of MTV. You might remember from the first part of this series that 2011 was the year that the network celebrated its 30th anniversary, but chose not to go ham on celebrations, figuring that its average viewer didn't particularly care. (There's no reference to the milestone anywhere in the 2011 show, assuming that I didn't miss anything. The only nods to MTV's past are the Moonman statues themselves, which—because I haven't said this anywhere yet—stem from its original Moon landing bumper.) Tonally, this was a massive shift from 2001, when—to recap a bit of the second part of this series—the network produced multiple MTV20 specials to run throughout the summer, and then hosted a live event that was completely separate from the VMAs. In 2011, MTV itself seemed to know that something was over. The rest of this instalment will be about me trying to put my finger on what.

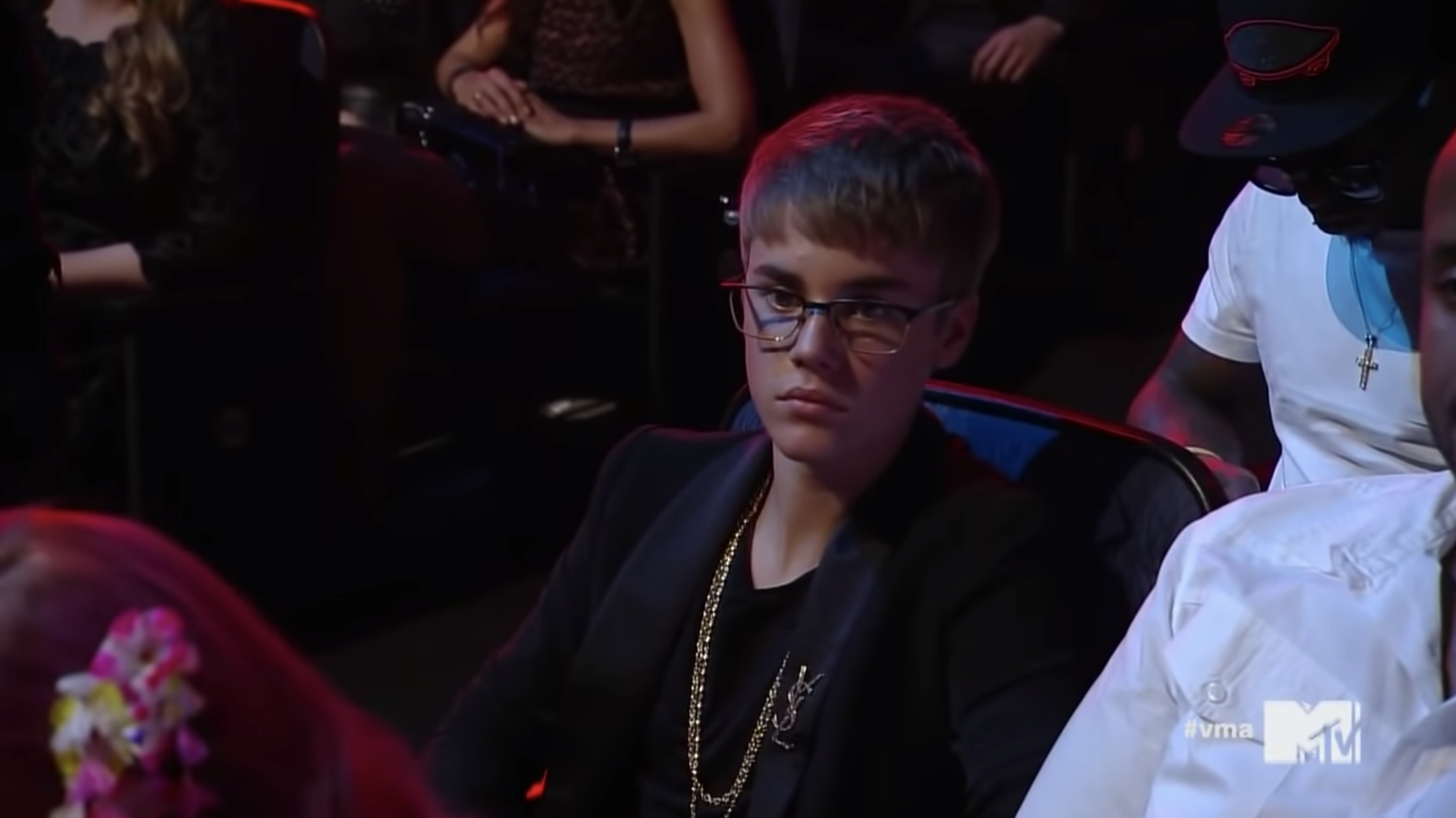

The 2011 VMAs are a fun and often funny show to watch a second time around. Gaga opens things as Jo Calderone, the male alter ego associated with her Born This Way era. He, Jo, begins with an X-rated diatribe against Gaga, who's apparently recently left him, and eventually introduces a performance of "Yoü and I" (2011) featuring Queen’s Brian May. Justin Bieber spends most of the night staring blankly at the stage, a sight that the New York Times would later declare perfectly encapsulated the evening. Beyoncé announces her pregnancy with Blue Ivy during a performance of “Love on Top” (2011).

After a tribute to Britney, who hadn't made a VMAs appearance in a few years, the artist born Stefani Germanotta Jekyll and Hyde-s her way through a speech presenting her with the Vanguard award. Gaga calls Britney one of her biggest inspirations, while Jo tells us, “I used to hang posters of her on my wall and touch myself when I was layin’ in bed.” (They slowly lean in for a kiss while on stage together, until Britney pulls away and says, "I've done that already.") Jessie J performs for the in-room audience during each of the commercial breaks, which means that we cut to sponsored messages from 5 gum and Taco Bell every time she starts singing. (She’d also recently broken her foot, so she spends most of the night sitting down on her designated stage off to the side.)

As with practically any VMAs show, there’s an expected cringe factor. Kevin Hart gives a speech expressing some confusion about Gaga’s opening performance (“It got a little masculine, but then it came around”), complaining that MTV wouldn’t let him host the show this year, and warning everyone in the audience not to pick up an STD from the Jersey Shore cast. (Later in the evening, said cast presents an award with, of all people, the late Cloris Leachman.) Russell Brand gives a not-amazing tribute speech (in my opinion, at least) to Amy Winehouse, who'd died the previous month. He'd been chosen for the job because the two were IRL friends, but a lot of it comes across as being in poor taste, especially a decade after the fact. (Tony Bennett thankfully follows with his own, more thoughtful one, and Bruno Mars performs a great cover of "Valerie.") Jonah Hill co-presents an award with Nicki, where their back-and-forth is entirely about Hill having recently lost a bunch of weight. Entertainment Weekly put it best when it called the evening "a beautiful festival of awkwardness."

For me, nothing is more awkward than Katy and Kanye West accepting Best Collaboration for “E.T.” (2011). Katy awkwardly makes a joke in reference to Kanye having interrupting Taylor on the 2009 VMAs stage, then congratulates him on winning his first Moonman, when it’s actually his third. “I have more,” Kanye says, his tone something between deadpan and insulted. “You have more!” Katy responds—careful to make it a statement instead of a question, and doing her best Rose Byrne as the Duchess of Polignac.

There's also a funny time-capsule element at play, again as with any of the broadcasts that I've consulted for this series. There are the circa-2011 couples: Katy and Russell, Justin and Selena Gomez, Britney and Jason Trawick. Jennifer Lawrence has sent in an exclusive clip from the set of the first Hunger Games movie, which won’t come out for another half a year. Jay-Z and Kanye have released Watch the Throne (2011) just three weeks prior, and perform “Otis” (2011) together. Rebecca Black stars in one of the pre-recorded skits; LMFAO pop up more than once throughout the night.

Something else that I couldn’t help but note, and which I’m very sadly including among the things that feel time capsule-like, is that every single winner thanks their director. The sole exception is Justin, who wins Best Male Video for “U Smile”; he manages to thank both God and Jesus, just not Colin Tilley. Though I’ve never formally tracked this sort of thing, I can say with confidence that it’s become more and more rare in recent years for artists to thank their director at the VMAs—rare enough that it sticks out anytime someone does.

To prove it, I skimmed the 2015 broadcast; there are five acceptance speeches, and only in two are directors thanked. Taylor actually brings Joseph Kahn up with her on stage to accept Best Female Video for “Blank Space” (2015), then lets him give his own speech. “When you invite a director to stage—this is why MTV doesn’t do it—you’re gonna thank a lot of crew,” Kahn says. This trend is, of course, consistent with what I was talking about earlier, where the VMAs have become less and less about the artistry of music videos themselves. But what's interesting about Kahn's speech is the suggestion that MTV is not only complicit in the shift, but playing an active role in it.

Coming back to 2011, there’s a sense that a changing of the guard is taking place in terms of artists, but perhaps one that’s only evident 10 years on. Adele makes her VMAs debut, performing “Someone Like You” (2011). Tyler, the Creator wins Best New Artist. Combined with names like Rebecca Black and LMFAO, we were suddenly looking at a whole slew of names that MTV hadn't helped to break—that honour having gone to YouTube. (These days, it's still YouTube, but it's also TikTok.) Indeed, there was a second, more industrial/technological changing of the guard happening synchronously. Jo Calderone is a great example of how there was an assumption on Gaga’s part—and perhaps even MTV's part—that you’d gotten your context on the alter ego from somewhere else. Whereas TRL would have been the one-stop shop to get an explainer on the character had Gaga emerged during that era, things were different now that she was communicating constantly with fans via Twitter as well as her Gagavision transmissions on YouTube.

While MTV can still do certain things for an artist in 2021, especially in terms of promotion, the reality is that music videos are now predominantly accessed by other means, and that brand control mostly happens on social media (as well as via documentaries, a space where the network no longer has the foothold it once did). Even one-off live performances, the kind that artists previously might need the VMAs for, can now be streamed directly into fans' homes. (A perfect example is Dua Lipa, who declined to perform during the 2020 show—something that would have been unheard of even a decade ago—and then hosted her Studio 2054 livestream a few months later. The power dynamic is just not what it was.)

There have been plenty of memorable VMAs moments since 2011, but I'm not sure that the broadcasts themselves have remained as gripping from beginning to end. Most people I know who still watch them year after year do so to see specific performances that have been advertised (or are rumoured, if you're of the Beyhive persuasion). I can barely get myself to care about the stuff in between anymore in light of how it's more or less Stan Twitter choosing the bulk of the winners. The numbers indicate that I'm not the only one who feels this way: 2011 marked a ratings high, not just for the VMAs but actually MTV in general, while 2019 marked an all-time low. It seems that the FOMO draw has petered out now that everything worth revisiting from each live broadcast finds a second, more fruitful home on social media (where the network puts the majority of its energy these days). And, since MTV is no longer the water cooler that everyone flocks to on the other 364 days of the year, there's a good chance that you're not going to be terribly familiar with every single presenter and nominee, which can make aspects of the show disorienting.

This year's VMAs—hosted by Doja Cat, which I think is an extremely smart choice—will take place on September 12 at Barclays Center. Coming off of last year's very uncanny-valley show, I truly have no idea what to expect this time around. But I hope that reading this series has at least given it some stakes, the way writing it certainly has for me. Thank you to everyone who's been following along, and may literally anything but Ed Sheeran's "Bad Habits" (2021) win Video of the Year. ●

Mononym Mythology is a newsletter about mostly pop divas and their (visual) antics. It’s totally free, but if you got something out of this instalment, consider buying me a coffee. The best way to support my work otherwise is by sharing it. You can subscribe here, and you can find me on Twitter and Instagram.