A Moving-Image History of Parkwood Entertainment, Vol. II

This is the second of a four-chapter series on Beyoncé’s Parkwood Entertainment and its extensive film output.

In this chapter, I follow the company—initially called Parkwood Pictures—on its early filmmaking adventures, from Cadillac Records through the 4 era. It’ll make the most sense if you’ve read the previous chapter, where I dove into the years that led up to the company’s founding. There had also been an introduction, where I explained how this series came to be and what I’m hoping to achieve with it.

This project is being published for free, but please subscribe if you’d like to know about new chapters as soon as they drop. You can read more about this newsletter here.

There’s a passage in Soul Survivors, the 2002 Destiny’s Child autobiography that I quoted from at length last time around, where 20-year-old Beyoncé writes of her admiration for Madonna—not her artistry, exactly, but her ability to spin professional hiccups to her advantage. “She is a mastermind of the music business,” Beyoncé argues in the book. “Every obstacle ever placed in her path, she’s picked up and run with it—all the way to the bank.”

What the young star says next suggests that this is an observation based on more than a decade and a half spent paying attention to the older one. “MTV banned her video?” Beyoncé writes, referring to when the network denied the scandalous “Justify My Love” (1990) any airplay:

Okay—she sold it! If anybody said something bad about her—like when the press found out about her posing for nude pictures—her response was something like, “Yeah, I did. *And*?” It’s one of the reasons she has been so successful. She’s turned all the negative things into positive things. And that’s what I try to do.

I quote this passage in part because in the next chapter, 30-something Beyoncé will draw a link between her own Parkwood Entertainment and Maverick, the company Madonna co-founded in 1992 that helped her—to paraphrase Beyoncé—be a powerhouse and have her own empire. But I mostly cite it because the story of Parkwood, like that of Maverick, is really a story about control (to borrow phrasing from a different idol of Beyoncé’s). Madonna’s company didn’t specifically stem from Playboy and Penthouse publishing her nudes from before she was famous, nor MTV being less than game when she’d just made one of her greatest videos. Nevertheless, it and Parkwood would be united by a basic idea: guaranteeing yourself some power in an industry hell-bent on humbling you.

If the story of Parkwood is one about control, then Beyoncé spent much of the previous chapter desiring more of it—only having so much say over the release dates and quality of the movies she appeared in, being disappointed with how someone else’s camera crew broadcast a performance, having to pay a third party to use footage of herself, watching rumours about supposed beef with one of her co-stars escape her grasp, and finding herself booted off of an Oscar ballot. For the first decade of her career, every triumph had seemed to come with a requisite humbling.

That’s no less true of the chapter below, but the humblings over the half a decade I cover will feel less and less consequential as the infrastructure around Beyoncé solidifies. Storms are storms, but they’re easier to weather—or at least navigate with dignity—if you’ve already got certain walls up.

Though you’ll often see people locate Parkwood’s origins in the early 2010s, Beyoncé and I both tend to go with 2008, the year she turned 27. As is her wont, she’d begun that one with a secret: while in Paris in December shortly after the conclusion of the Beyoncé Experience, she and Jay-Z had gotten engaged on the fourth of the month, his birthday. And as she’d later share in a documentary, they celebrated by catching a nude cabaret show at Crazy Horse.

In the run-up to this wedding that the world wouldn’t be looped in on, Beyoncé made her first big splash of 2008 on the Grammys stage in February. Following an introduction by Cher, she performed a mostly-spoken tribute that positioned her as a sort of concoction of Black women stars past. “When I was a little girl, I dreamed of being on this stage,” she began, “but I knew I needed all the right elements.” She then proceeded to list them one by one—Donna Summer’s beat, Mahalia Jackson’s spirit, and so forth.

If Beyoncé named 13 women, most were/are best known as musicians, but almost all happened to have some kind of relationship to cinema. We’ve talked a bit about Janet Jackson, Whitney Houston, and especially Diana Ross’s connections to that world; Aretha Franklin and Donna Summer had their own, very different ones. Another notable inclusion was Lena Horne, a screen legend at least a dozen ways but also one of numerous Beyoncé idols who’d starred in The Wiz (1978).

Mahalia Jackson, for her part, made several film appearances in the late ’50s and early ’60s, including in Douglas Sirk’s Imitation of Life (1959), which Beyoncé will later in this story be (somewhat dubiously) rumoured to be remaking. There’s also the matter of “Take My Hand, Precious Lord,” a song closely associated with the gospel legend that had particular significance for the Knowleses; Beyoncé will not only perform it in the next chapter but release a short film about performing it. Even if some of these dots only connect accidentally or with the benefit of hindsight, they still connect.

“But there is one legend who has the essence of all of these things,” Beyoncé continued, before asking the Grammys audience to give it up for a 14th name, whom she simply called “the Queen” before exiting the stage. From there, Tina Turner—who, at the time of her death in 2023, boasted a 56-year screen career—kicked off a medley of greatest hits. And eventually, she called “Ms. Beyoncé” back out onstage to duet “Proud Mary,” the song Beyoncé had performed for her at the Kennedy Center a few years prior.

“I can’t believe that just happened,” a flustered Beyoncé told one reporter after the show. “I’ve always wanted to be so much like her, and now I’m just so excited ‘cause I have her blessing.” In all, the star would spend much of 2008 in this mode: not just drawing connections between herself and various performers she admired, but actually seeking and—for the most part—securing their endorsements.

A little after the Grammys came announcements that Beyoncé would soon be shooting a pair of new movies, both of which she’d wrap ahead of her third solo album expected later that year.

The one she’d make first, set for a December release, was Darnell Martin’s Cadillac Records (2008), broadly about music executive Leonard Chess (Adrien Brody) and his famed Chess Records. We follow Chess, a Polish-Jewish immigrant trying to make something of himself in Chicago, as he gets into the business and crosses paths with a horde of blues and rock legends—Muddy Waters (Jeffrey Wright), Howlin’ Wolf (Eamonn Walker), Chuck Berry (Yasiin Bey, then still Mos Def), and more. As with Dreamgirls (2006), Beyoncé would be playing a take on a real-life icon, this time a talented and troubled Etta James, a love interest of Chess’s in the film—and “the first African American woman to cross over on the radio,” as Beyoncé would say.

With Cadillac Records, writer/director Martin was making her return to theatres after a substantial gap; following her critically acclaimed debut, I Like It Like That (1994), she believed that she’d been “blacklisted in the industry for speaking out against racism and misogyny,” as the New York Times put it. She apparently wrote her vision of James with Beyoncé in mind, and though the prospect of playing the then-living legend was terrifying, the star signed on. “Darnell brought something out in me,” she’d say, “and I think it was because she’s a woman … She knew how to talk to me, and I knew what she meant.” Indeed, in almost a decade of appearing in narrative features, Beyoncé hadn’t yet gotten to work with a woman director on any.

Etta James was a grittier role than she’d ever pursued; aside from several emotional and sometimes raunchy dialogue scenes, there’d be a particularly unglamorous one where the character is revived after a heroin overdose. But as one piece explained, “[Beyoncé’s] mother, Tina, who vets all the scripts that are submitted to her, flagged this one as a keeper, noting that the hard-living, emotionally scarred Ms. James could be the role of a lifetime.” Ms. Tina would actually claim that she “kind of twisted Beyoncé’s arm a bit to do this one,” her daughter being extremely busy in addition to scared out of her mind.

In keeping with all of these firsts, Beyoncé chose to do yet another new thing as far as narrative work and came aboard as executive producer. “The film was initially offered to her just as an acting vehicle, and it was something she really responded to in terms of material,” her film agent Andrea Nelson Meigs would tell Billboard. “But she was drawn especially to her role because of what Etta James represented in the music world, and … wanted to get involved in a more intricate way—both in development for casting and music.” The same article explained:

Beyoncé became one of the boosters for the film, helping to bring [together] all the different elements … She aided actors with their scripts, shared her thoughts on how scenes should be shot and even got involved with lighting.

Again in an echo of Dreamgirls, Beyoncé’s commitment to the role of James was supposedly exemplified in part by a change in her weight, this time in the other direction. Now, however, the star was acting at the request of her director, who’d later take multiple interviews to express her shock that her leading lady complied. (If coverage of the Dreamgirls dieting skews irresponsible from a present-day vantage, that of her weight gain for Cadillac Records is often just silly.) “She was willing to do the work,” Martin would say:

To put on the weight and not be glamorous, to go to a very ugly place and play someone she’s never been: a drug addict, abused, abandoned by her parents. She was very excited to tear her image apart. When she first saw herself on film strung out, half-naked, overweight in the bathtub… she was so *happy*.

Despite my scoffing at the body stuff, “excited to tear her image apart” is crucial and something I wouldn’t want to gloss over. The rest of 2008 would push Beyoncé into a new tier of superstardom and—at least as she saw things—artistry, and though Cadillac Records isn’t always remembered as having been part of that push, her own comments declared it a main catalyst. Already deep into work on her album, she found that the film was changing its creative direction, turning the project both more personal and experimental. “The music I made before and after the movie [was] very different,” Beyoncé would say. “I was a lot more bold and fearless after I played Etta James … I think that’s why I love doing movies so much, because it’s not just an art form. It changes my life and my music and the way I look at things.”

At the time of filming, the star occupied a weird in-between zone on her artistic and coming-of-age journeys. On the one hand, she was a fast-rising 26-year-old who’d soon be none other than Mrs. Shawn Carter; on the other, she was still professionally and reputationally someone’s daughter, known especially for her shyness and good behaviour. “Role model” remained a title that she embraced and even used herself, and I’ve read multiple things in recent months that mention her as someone Sasha and Malia Obama looked up to. It’s almost like James provided her with an excuse to start safely teasing out the actual Beyoncé at the centre of it all, whoever that happened to be. “She was a tough woman,” the star said in one interview. “She spoke her mind, she had no boundaries. She made whatever genre of music her own, and it taught me a lot about being a superstar and a gutsy woman.”

As had also been true of playing Deena, Beyoncé’s preparations for the role went beyond the superficial: she’s described learning almost everything she needed to from James’s memoir, Rage to Survive (1995), and scoured YouTube for any footage she might find helpful. But perhaps most interesting, she befriended some recovering addicts at a local Phoenix House to better understand James’s struggles with heroin. On the Cadillac Records press tour, Beyoncé would say she was very grateful to these women, and suggest that the experience had been eye-opening with regard to stereotypes. She’d also gift the organization with her salary from the film.

“I wanted to do [James] justice,” Beyoncé summarized, indicating that playing her was again a huge psychological challenge. “You couldn’t talk to me … It was one of the hardest things I’ve ever done.” Following extensive rehearsals with the cast, she knocked her scenes out in a little less than a week, apparently going home each day “with swollen eyes and with a big attitude.”

Almost immediately after completing work on the film, Beyoncé and Jay-Z were quietly married in his Manhattan penthouse on the fourth of April, or 4/4.

Upon returning from her honeymoon, Beyoncé filmed the second movie that had been announced after the Grammys: Steve Shill’s Obsessed (2009), an equal parts fun and ridiculous update of Adrian Lyne’s Fatal Attraction (1987), to be released sometime the next year. The star would be executive producing this one, too—as would her father, who doesn’t seem to have been involved in Cadillac Records beyond co-releasing its soundtrack.

In Obsessed, Beyoncé plays Sharon, the headstrong wife—and former secretary, in a small but relevant detail—of finance power-player Derek (Idris Elba) as their family is terrorized by a temp (Ali Larter) at his company. Though the star was spotted on the film’s set in June, she spent the summer of 2008 relatively low-key as she put the finishing touches on her album.

That all changed at Fashion Rocks in September, where Beyoncé performed three times, all in the name of cancer research. Infamously, there was “Just Stand Up!,” where she was one of a dozen-plus women featured on the semi-chaotic charity single. She was also brought out during Justin Timberlake’s Motown-themed set to duet Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell’s “Ain’t Nothing Like the Real Thing.”

Most relevant, however, she used the event to kick off Cadillac Records promo in earnest. After donning an Etta James wig—which she also wore, for some reason, during “Just Stand Up!”—this third performance began with a Beyoncé-narrated montage of James, where she praised “music’s original bad girl” for her “platinum hair, wildcat eyes … Fellini-esque sexuality, and dangerous voice.” One of the photographs then faded out as Beyoncé’s live image faded in, the two women’s features having been overlaid, so that Beyoncé could perform “At Last,” the ’40s tune James had made her own with her 1960 recording.

Towards the end of the song came a twist: the star was helped down the stairs to where James herself turned out to be sitting in the front row. Beyoncé grabbed the blues legend’s hand, turned her around to show her the standing ovation she was receiving from the room, and gave her an excited hug. Another hard-won blessing from a performer she admired? It sure looked that way to anyone watching from home.

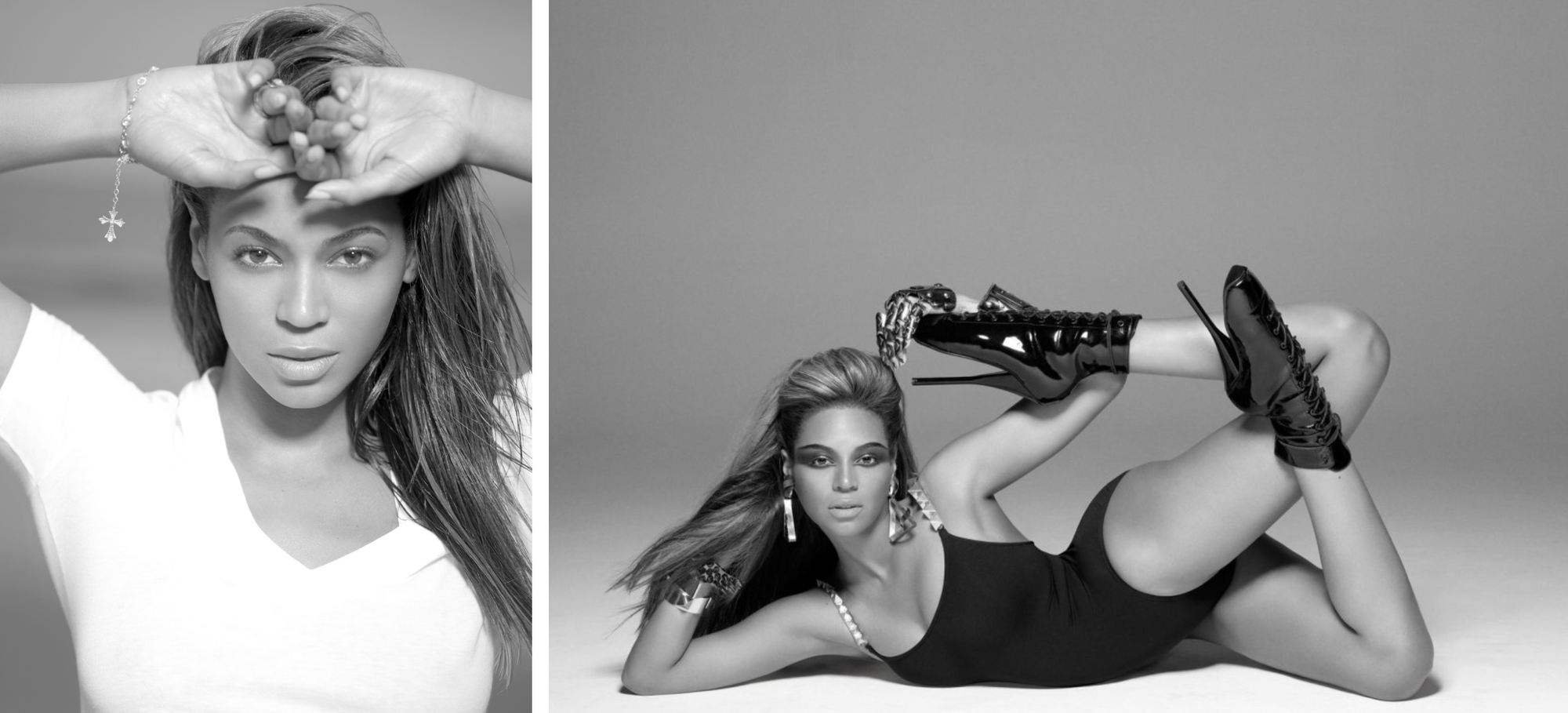

Beyoncé would spend the fall unrolling I Am… Sasha Fierce (2008), a two-disc concept album for which she halved herself: on one disc, she was the besotted newlywed recently renamed Beyoncé Knowles-Carter (though not yet using that name publicly), and on the other, she was the alter ego she’d created many years prior to help her give 100% onstage. “I kind of get into character like I get into character for a movie,” she explained of Sasha to one journalist.

As Beyoncé described the album concept, “I have the love songs that are probably the most innocent and pure and vulnerable songs I’ve ever recorded, and then I have the really over-the-top sexy, sassy, fiery songs that represent Sasha Fierce, and I wanted to give my fans both sides because that’s who I am.” In its promotional imagery shot by Peter Lindbergh, “Beyoncé” held a rosary in soft fabrics and minimal makeup, while the smoky-eyed “Sasha Fierce” pretzelled herself on the floor and wore a single MJ-esque robo-glove.

This duality was also reflected in the album’s rollout, where the first four singles were released as two sets of pairs that dropped at once; the world got “If I Were a Boy” and “Single Ladies (Put a Ring on It)” in October, and the same would happen with “Diva” and “Halo” in January. On the press tour, Beyoncé sometimes cast Sasha Fierce as the knowingly radio-safe half of the project, and I Am… as the one she felt had entered her into new territory. And though I wouldn’t have necessarily guessed this, it was the I Am… tracks that she credited to playing Etta James; there are certain interviews where she makes it sound as though the entire disc originated out of Cadillac Records. She even told one interviewer, right on the nose, “[James] gave me a better understanding of who I am.”

While most people consider I Am… Sasha Fierce to be in the bottom rung of Beyoncé’s discography these days, it’s hard to overstate how instrumental it was in cementing her as an icon. The album had nine singles, with six peaking in the top 40 and four in the top ten. Multiple lyrics from the album would enter the public lexicon, and it still generates the odd meme to this day. And while we’re going to properly get into the videos later, its most explosive one was tied up in everything from a viral dance craze, to the election of America’s first Black president, to a defining pop-culture feud of the 21st century.

For the Jake Nava-directed “Single Ladies,” Beyoncé and two dancers—all in black leotards and the classic Sasha Fierce half-up—recreated a 1969 Bob Fosse number called “Mexican Breakfast.” She was later accused of trying to pass the routine off as her own, which elided two important details. The first is how choreographers Frank Gatson Jr. and JaQuel Knight had turned Fosse’s original into one that now included J-Setting, a dance style originating with majorettes at Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs).

The other detail is the half a decade that Beyoncé had by that point spent working Fosse into her videos and tours, not to mention name-checking him in behind-the-scenes content. “Mexican Breakfast” wasn’t even the only reference to the famed choreographer and director in “Single Ladies”: the three women run up the wall in a nod to Sweet Charity (1969), and the costuming had been inspired in part by All That Jazz (1979).

But anyway, the song itself is directed at a man who blew his chance with the narrator by not proposing; at the end of the video, when we zoom in on Sasha Fierce’s robo-glove, it’s wearing a lookalike of Beyoncé’s actual engagement ring—in a sort of admission that she’d gotten married that year. “Single Ladies” kept with the album’s stated visual ethos of “natural and simple and graphic,” but its success took its makers by surprise, not necessarily intended to eclipse its splashier, costlier, dare I say cinematic twin video as dramatically as it did.

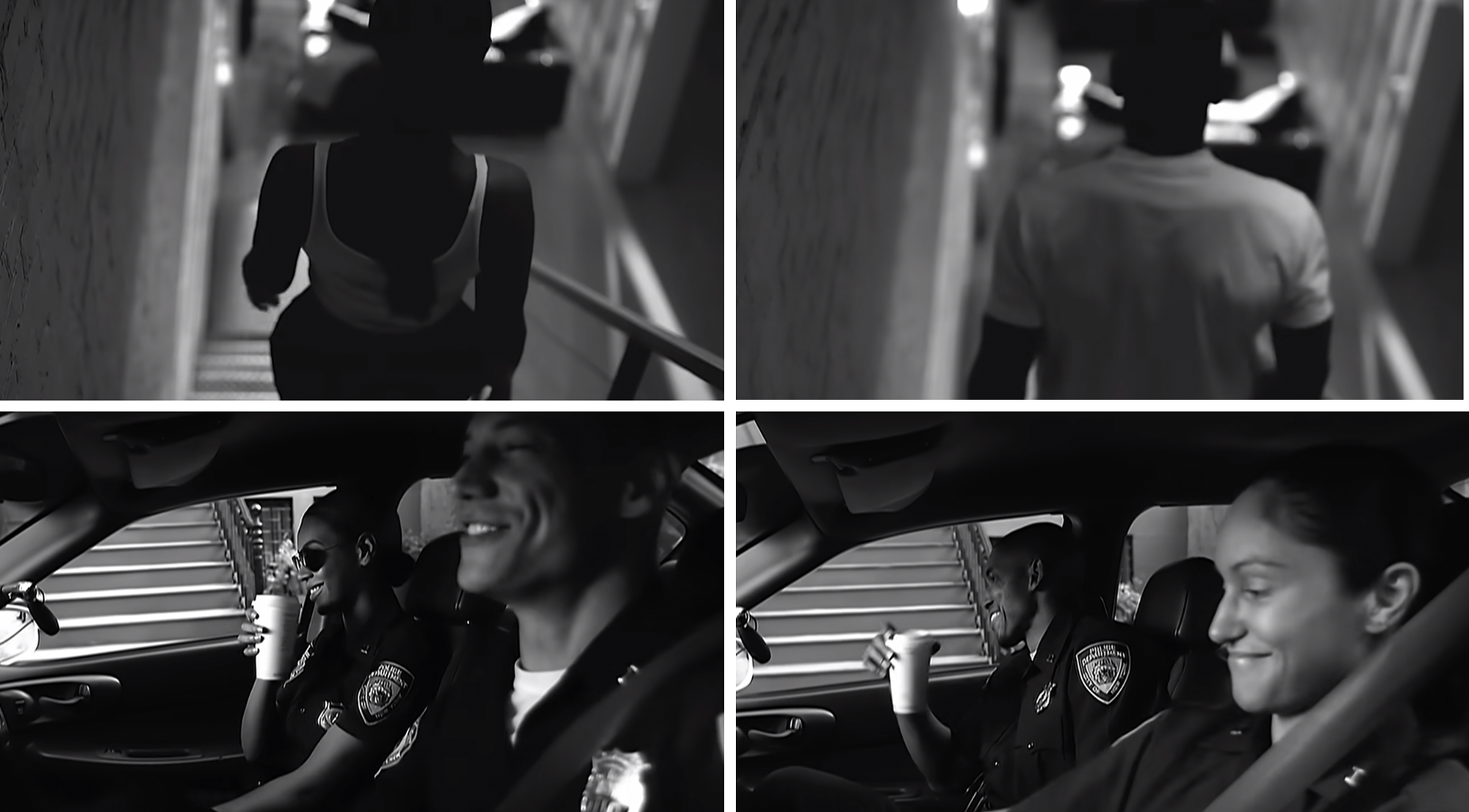

In “If I Were a Boy,” also directed by Nava, Beyoncé plays a cop toying with the emotions of the man fretting over her fidelity from home—until the characters swap bodies during a dialogue scene halfway through, in what becomes a commentary on gendered double standards in (straight) relationships. “It’s kind of like Freaky Friday,” Beyoncé had told Billboard ahead of the tandem releases, in an article that didn’t bother teasing the content of “Single Ladies” at all.

Both songs would be top-three hits, so “If I Were a Boy” obviously did just fine. But one might still extrapolate that the comparatively phenomenal “Single Ladies” better reflected what the public actually wanted from Beyoncé in 2008. Fans may not have minded her injecting her work with storylines and dialogue and some commentary—making a little movie, essentially—but most of the world was perfectly happy just to watch her sing and dance to a new uptempo.

About a month after the two releases, on the fourth of November, Barack Obama was elected the 44th president of the United States. I Am… Sasha Fierce hit stores a week later.

Beyoncé’s earliest YouTube uploads, at least that still remain on there, are from the same November. And since she’ll later choose the platform as the release method for certain films, I’ve had to decide case by case whether a given video should be considered among her filmography, or even just mentioned in this story. (It’s not always as obvious as it may seem.)

The first video on her channel is a teaser for her 2008 episode of Walmart Soundcheck. The retailer used to produce segments featuring a live set and interview with a popular artist, and you could either download these or watch them in a Walmart while you shopped.

The live bits of Beyoncé’s episode, released in mid-November, came from her set at the Bermuda Music Festival the previous month. In lieu of an interview, however, there were doc segments—just under 20 minutes combined—that pulled together videography from the past little while. Interestingly, IMDb credits the episode to Mark Ritchie, a prolific live director in the music space who’ll later be credited on a number of Beyoncé projects, both released and unreleased.

There’s a stretch of the episode where we see the star preparing I Am… Sasha Fierce, explaining in what was starting to become her trademark lulling voiceover:

I’m a human being. I cry. I’m … extremely sensitive, and my feelings get hurt. And I get scared, I get nervous, just like everyone else. And I wanted to show that on this album … Even with my videos and my photoshoots, everything’s a lot more natural and broken down.

As with the untitled Beyoncé Experience documentary in the previous chapter, there’s a segment on her commitment to charity, where virtually all of this footage comes from her 2007 tour (some of it being the Ethiopia stuff we’d seen in the previous film). Eventually, she settles in Bermuda to rehearse her festival performance… also taking the travel opportunity to shoot a campaign for House of Deréon, the clothing line she used to design with her mother.

If this is all reading vaguely chaotic, you aren’t imagining it: in the years leading up to Life Is But a Dream (2013), there were a couple of Beyoncé projects like this, where you could sense the star becoming excited about the documentary format and seemingly throwing in anything she had on hand when she got a chance to make one. By this time the next year, she’ll have realized that there’s clearly an autobiographical feature in her future, but first there would be some releases with somewhat sprawling narratives.

And in an important asterisk to what I just said, there’s a moment in the episode where she proves herself to be a flawed historian of her own life. “I decided I wanted to perform ‘At Last’ for the first time with my band,” she narrates of her Bermuda set, before following that up with a bald-faced lie: “It would also be the first time I sang the song live. I was excited to see how the audience was gonna respond to something they’ve never seen.”

Though this wasn’t the kind of revisionism that was going to hurt anyone—we’d all just watched Beyoncé perform the song for Etta James—it’s in line with something you’d have to watch out for with her in the future. There was the star’s life, and then there was her life as she presented it in her documentaries.

Cadillac Records was released in December, a few weeks after I Am… Sasha Fierce. And while it wasn’t a commercial smash, nor even really a success—it made about $9 million worldwide, meaning it didn’t make its $12 million budget back in theatres—it marked an important milestone on Beyoncé’s journey as both a gracer and maker of movies. It takes her a full hour to show up as Etta James, but she goes on to deliver what’s easily her greatest dramatic performance in a scripted film. And she recognized as much, saying, “I’m the most proud of that movie, more than anything I’ve done so far.”

Though reviews of the film were mixed, most critics agreed that Beyoncé’s performance had been something special—“devastating” according to Vogue, and “inspired and persuasive” according to Roger Ebert. Even her onetime Golden Globe competitor Meryl Streep apparently congratulated her on the ‘rawness’ of it. “It’s startling to see Ms. Knowles—one of the few pop stars left with a wholesome, good-girl image—swaggering and swearing through her performance,” wrote the New York Times. It would take another half a decade for Beyoncé to start cursing in her music, yet here she was yelling out for a “fuckin’ bottle of gin!” on the silver screen. It wasn’t any surprise that the singing bits were great, but it didn’t feel so much this time around like they’d been her saving grace.

Beyoncé’s co-stars also went on record with their praise. Adrien Brody, with whom she shares her trickier scenes, admitted that he “didn’t anticipate her being as emotionally present and connected with the role as she was.” Jeffrey Wright would call her “an evolving, complicated young woman who is going to surprise some people who think they have her pegged.”

The problem, put bluntly, was that Cadillac Records flopped—whether because it was undermarketed, or the Recession, or any of the other theories put forward in this 2008 discussion forum. In any case, the underperformance not only doomed it to a lacklustre awards season but failed to transform Beyoncé’s screen reputation the way it had potential to.

Press coverage tended to mention that the star had executive produced it, but not so much that this second role went beyond a vanity line in the credits. In the opening moments of Cadillac Records, after we get the bumpers for TriStar and Sony Music Film, there’s a third one for a mysterious company called Parkwood Pictures, the font similar if not identical to that being used on the visuals for Beyoncé’s album:

The company’s name referred to one of the streets in Houston where she grew up, in a house that’ll become more significant in this series as it starts to appear in her films with curious frequency. So no matter how long it takes Etta James to arrive in Cadillac Records, Beyoncé herself hovers over the lot of it if you’re someone to whom the name Parkwood means anything. And that’s true all the way into the credits, for which she recorded an original song called “Once in a Lifetime,” a romantic doo-wop track with slight electronic flair. (Interestingly, she’d written it with the exact same team behind “Listen” from Dreamgirls: Henry Krieger, Scott Cutler, and Anne Preven.)

Another aspect of the film that reads differently now is its parallel storyline, about how indebted white rock is to Black country blues. (At one point, the not-yet-famous Rolling Stones briefly cameo to tell Wright’s Muddy Waters that they named themselves after his song “Rollin’ Stone.”) Beyoncé’s previous movie roles had sometimes posed opportunities to go deeper into some area of Black music and/or film history—Dorothy Dandridge becoming the first Black woman nominated for Best Actress in Carmen Jones (1954), the heyday of blaxploitation, Berry Gordy and the rise of Motown. But with Cadillac Records, the lesson was right there in the text, the characters not being stand-ins or composites the way they’d been in Dreamgirls.

In one interview, Beyoncé even characterized the film as educational:

This is really an important story, and it’s great that I’m able to … share this with my generation, because it’s a lot of things that I didn’t know, and I’m sure a lot of other people don’t know, and they’ll be educated. It’s the story of rock and roll.

If I’d published this series any earlier than now, I wouldn’t have been able to mention that the Cadillac Records soundtrack includes a Mos Def cover of Chuck Berry’s “Maybellene,” a sample of which appears on Cowboy Carter (2024). The 2008 film also has a scene where Berry learns that his song “Sweet Little Sixteen” has been repurposed—“note for note,” as he complains to his Chess Records colleagues—into “Surfin’ U.S.A.” by the Beach Boys, who are themselves sampled on Beyoncé’s eighth album.

“Beyoncé clearly seeks out role models and thumbs through music history the way some people browse catalogs,” wrote Geoff Boucher in a late-2008 profile of the star. “She carefully channeled the icy perfection of Diana Ross in ‘Dreamgirls’ and jumped at the chance to perform with Tina Turner at February’s Grammy Awards ceremony. Now comes her turn as Etta James, and, on Sunday, she will seek out her hero, Streisand; Beyoncé will perform ‘The Way We Were’ at the Kennedy Center Honors and she already has butterflies.”

There may have been a bit of a sense in the aughts that Beyoncé idolized, well, everyone, but you couldn’t accuse her of having bad taste. She’d also been pretty consistent with her references since her breakthrough: Streisand’s name came up twice in the previous chapter, with Beyoncé citing her as a musician-turned-actress she admired as well as a reference for Deena Jones’s mannerisms.

Ahead of performing the theme from Sydney Pollack’s The Way We Were (1973) that December—a performance for which she dressed up as Babs, just as she’d dressed up as Turner in 2005—she told Boucher for the L.A. Times that she considered Streisand a “career model,” adding, “I want to be like her. She is just the ultimate. And I want to be an icon too.”

In the same conversation, Beyoncé also threw a very different name into the mix:

I want to do a superhero movie and what would be better than Wonder Woman? … A black Wonder Woman would be a powerful thing. It’s time for that, right? … After doing these roles that were so emotional I was thinking to myself: “OK, I need to be a superhero.” Although, when you think about the psychology of the heroes in the films these days, they are still a lot of work … and emotional. But there’s also an action element that I would enjoy.

As a reminder, the star had appeared in that one “Listen” video wearing a Wonder Woman shirt. But she told the L.A. Times that she’d become especially interested in this idea after the Met Gala in May, where Lynda Carter’s ’70s costume had been on display. As per Boucher, Beyoncé had already “met with representatives of DC Comics and Warner Bros. to express her interest in a major role in one of the many comic-book adaptations now in the pipeline following the massive success of ‘The Dark Knight,’ ‘Iron Man,’ and the ‘Spider-Man’ and ‘X-Men’ franchises.”

Running alongside Beyoncé’s history at the movies are all the what-could-have-beens—movies she wanted but wouldn’t get (or that weren’t made in the end), movies she may not have actually wanted that badly, movies that were hers until life intervened, movies she was rumoured to be working on that potentially never existed, and so on. That Beyoncé campaigned for a DC superhero role is the earliest what-could-have-been I’m discussing in this story—I didn’t mention last time that she’d auditioned for Josie and the Pussycats (2001), a very different would-be debut from Carmen: A Hip Hopera (2001)—but it’s somehow neither the strangest nor the most compelling.

“It sure would be handy to have that lasso,” Beyoncé concluded. “To make everybody tell the truth? I need that.”

While Cadillac Records was nominated generously by Black organizations like the Black Reel Awards, NAACP Image Awards, and BET Awards—Beyoncé received acting nods from the latter two—the film was largely shut out by major film institutions. The sole exception came from the Golden Globes, with the star nominated for Best Original Song for “Once in a Lifetime.” The award eventually went to Bruce Springsteen and “The Wrestler” from The Wrestler (2008), and neither artist would be nominated at the Oscars in February.

As in 2007, however, Beyoncé not only attended the 2009 ceremony but participated in it, helping host Hugh Jackman carry out a big tribute to musicals. The segment was the show’s sole contribution from director Baz Luhrmann, whose involvement helped explain its jukebox approach. Beyoncé was surprise-introduced with a stretch of “Big Spender” from Sweet Charity, a number she’d by that point tributed on two different tours.

While clips from various movie musicals played behind her and her co-performers, she sang bits of everything from “All That Jazz” from Chicago (2002), to “One Night Only” from Dreamgirls, to “Don’t Cry For Me, Argentina” from the Madonna-starring Evita (1996). The medley also included a quick slice of “At Last,” a song that Beyoncé was beginning to uncouple somewhat from Cadillac Records.

A month prior, she’d fought back tears to perform the Etta James classic for Barack and Michelle Obama as they shared their first dance at the inaugural ball—the love song thus recast as a paean to racial progress, as critics observed at the time. (Two days before that, she’d performed “America the Beautiful” at the official inauguration concert, eventually joined onstage by several names that have appeared in this story—Springsteen, Tom Hanks, Josh Groban—as well as names that’ll appear later, like Stevie Wonder.)

A week after the inauguration, James told a crowd that Beyoncé was “gonna get her ass whipped … I can’t stand [her], she had no business up there singing … my song that I’ve been singing forever.” Though the blues legend claimed the next week that she’d been just joking, she still admitted to “feeling left out of something that was basically mine.” (These were only the latest in a string of less-than-impressed quotes spanning about a year.)

So here we found Beyoncé in late February, killing two birds at the Oscars. The medley not only telegraphed that she remained unafraid of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, but that she also planned to continue performing “At Last” in whatever context she wished.

The song was included, for example, on the setlist of the I Am… World Tour, which began the next month. The tour would take Beyoncé around the world for a year; we’ll be coming back to it, but you should assume as you continue reading that she’s embarking on her most ambitious live show yet in the background of everything else.

That same spring came Obsessed, a movie that would be ripped apart by critics but do well commercially, grossing more than twice its budget. Sharon Charles, the redheaded wife and semi-reluctant homemaker to Idris Elba’s Derek, was the first role of Beyoncé’s where she didn’t play a performer. (Though “Smash Into You”—from the deluxe edition of I Am… Sasha Fierce—plays during the final scene and credits, things are left there in terms of soundtrack stuff.) According to producer Will Packer, who’d originally brought the script to the attention of Beyoncé’s team, that was the whole appeal: “This was something very different than what she had done in the past, and I know she was looking for that challenge and welcomed this opportunity … something different from that global persona that she’s [worked] hard to create.”

For much of the movie, the star’s job as Sharon is to worry about her husband from the beautiful big house they’ve just moved into, where she takes care of their son and fantasizes about going back to school. But when Ali Larter’s Lisa—a stalker with her sights set on Derek—enters the picture and starts causing marital mayhem, Beyoncé actually gets something to do.

During what’s probably the film’s second-most infamous moment, Sharon and Derek do the dialogue scene from All Too Well: The Short Film (2021), down to the hair and costuming. Unsure whether he’s cheated but knowing he’s lied regardless, she sardonically suggests a packing list for him—including “your prophylactics if you think you need ‘em”—and then screams at him to get out of her house.

The film is best remembered, though, for its climactic fight between Sharon and Lisa, a ten-minute sequence culminating in a Fatal Attraction-esque almost-death (Lisa falls from the attic into a glass coffee table on the ground floor) before an actual one (a chandelier then falls on top of her, finishing the job). Like the previous encounter, this one is rife with one-liners on Sharon’s part—“I’m gonna wipe the floor with your little skinny ass,” for example—and made extra dynamic because Sharon wants Lisa to suffer but, as it turns out, not die gruesomely in her living room while she watches.

Interviewed for Vogue around the film’s release, Beyoncé was asked by Jonathan Van Meter about the ease with which she seemed to deliver anger onscreen. “Everyone has it in them,” she responded. “I always have to be so put together, I always have to be pleasant. But sometimes I want to scream and holler, and I’m able to use the characters to release whatever pain or frustration has built up in me.”

As with all the roles in this series, I’ve done a lot of thinking about why Beyoncé may have taken this one in Obsessed, especially given the executive producing. (At one point, she arrived for work with pages of typed-up notes on the script.) She’s allowed to do things just for fun or money, though she was famously short on time and presumably not all that cash-strapped. She wasn’t starved for film offers, either; in various interviews she gave during the period covered in this chapter, she mentions having anywhere between three and ten scripts on hand.

I believe Will Packer when he says that Beyoncé was excited about playing a non-performer, but I don’t believe it was that simple. I’d even push back on the idea that Sharon was “something different from that global persona [Beyoncé had worked] hard to create,” since playing her involved the exact same duality as I Am… Sasha Fierce; depending on the scene, she’s either the loved-up wife or the fiery protector you shouldn’t mess with.

But to elaborate on that thought, one wonders whether there was some interest Beyoncé had, optically, in making a movie where she (eventually, after a brief separation) stands by her man as their marriage is threatened by an interloper. The crucial difference between Fatal Attraction and Obsessed—quality aside—is that Derek Charles, unlike Dan Gallagher, has not cheated with this woman, however much Lisa is making it look that way.

There was also a racial element that hadn’t existed in Adrian Lyne’s erotic thriller: part of the underlying tension in Obsessed comes from Lisa being a pretty white lady who’s lying left and right about her Black boss, successfully sowing doubt in the minds of his all-white colleagues and the white detective assigned to his case. (That Sharon is someone he originally picked up at work doesn’t help, either.)

Some of this might be a lot to read into a film made almost a decade before Lemonade (2016), but the years leading up to the later project were beset by cheating rumours on Jay-Z’s part—and Beyoncé had churned out quite a few bangers about ringing the alarm on men who were untrue and had mistresses.

Even if it’s ultimately a different argument, it was validating to read Jason King observe something related about Obsessed, in a 2019 piece on Beyoncé’s acting that I cited throughout the last chapter: “It served a purpose: to transgress against [her] and Jay-Z’s much publicized off-screen marital bliss. In a way, the film arguably prefigured the relationship cracks and fissures that later became the crucial themes for her groundbreaking 2016 [visual album].” Whatever the star was riffing on/setting up—even if she wasn’t riffing on/setting up anything—it was a fascinating movie to film shortly after your own wedding.

But no matter these speculations, it says something that when Lemonade came out—and when Cowboy Carter followed “Jolene” up with “Daughter,” a song about beating the hell out of a woman in the bathroom of an event—people made memes out of the bloody fight scene from Obsessed.

The star’s recent film work was one of the main focuses of Van Meter’s Vogue cover story, and it’s an interesting read as a relic of a time when you could still do actual journalism in a cover story of Beyoncé. One quick example, on Obsessed: “The best that can be said for this movie is that it is destined to become a camp classic.”

The piece, though, is altogether optimistic about her future in this second medium. Van Meter is particularly complimentary about her performance as Etta James: “Like most people, you probably missed her role in last year’s critically acclaimed Cadillac Records, and that’s a shame.” In the years since its release, the film has typically been written about this way, as the would-be gamechanger for Beyoncé’s screen career that no one saw.

“I’m finally connecting the way that I connect with music,” she says of acting. “I’m getting lost in the movies the way I get lost onstage.” There are also co-signs from Hugh Jackman, who has “no doubt she’ll win an Oscar one day,” and Baz Luhrmann, who predicts, “I’m sure that there is a dramatic cinematic life for her … It’s been a long time since we’ve seen that kind of performer, like Barbra Streisand and Diana Ross, on the screen.”

Van Meter also inquires about the dynamic between the star and her parents. Ms. Tina, as always, is positioned as the genial vetter of screenplays that come her daughter’s way. Initially, Beyoncé says of Mathew being her manager, “The best thing is having someone I trust.” But pushed a little on this, she adds, “It’s definitely tense. And if there’s one person in my life I argue with the most, it’s him. But it’s business. It’s always about business.”

“Their whole lives are not… me,” the star concludes. “But if they wanted to retire, I’m sure we would figure out who would help me.”

In June, Beyoncé released a DVD called Above and Beyoncé: Video Collection & Dance Mixes (2009), featuring the so-far six videos from I Am… Sasha Fierce. (A few more—“Sweet Dreams,” “Video Phone,” and “Why Don’t You Love Me”—would follow later.)

The project came with a 20-minute short called Behind the Scenes: The Videos (2009), directed by the star’s longtime videographer, Ed Burke. Bolstered by footage from rehearsals and shoots, she spends a couple of minutes talking about the making of each video before moving on to the next. (“Sweet Dreams” is included despite not being on the DVD, since the video wouldn’t come out for about a month. It would later get an extended making-of segment, where Beyoncé name-checks Hellraiser and talks about the cinematography reminding her of “the old MGM musicals.”)

With the odd splash of colour, especially as the era progressed, the visuals for the album were almost entirely black-and-white—apparently in part to spite a market research agency that claimed fans didn’t like when Beyoncé used B&W photography. Taken as a whole, they’d largely be directed by names already familiar to us: Jake Nava (“If I Were a Boy,” “Single Ladies”), Melina Matsoukas (“Diva,” “Why Don’t You Love Me”), Sophie Muller (“Broken-Hearted Girl”), Hype Williams (“Video Phone”), Frank Gatson (“Ego”), and Beyoncé herself (“Ego,” “Why Don’t You Love Me”). The two new additions were Adria Petty (“Sweet Dreams”), daughter of Tom but an accomplished artist in her own right, and Philip Andelman (“Halo”), who’d previously done a bit of work for Jay-Z and Kelly Rowland separately.

“Halo” featured another of the album’s more ambitious concepts, but the version the world saw had been significantly defanged from the original. In the released cut, Beyoncé is an angelically beautiful woman in love with her handsome man (played by Michael Ealy, who’d turned down “Irreplaceable” a few years prior). He watches her rehearse choreography; they cuddle on the couch; they joke around while brushing their teeth. But the video’s making-of segment featured footage of a femme fatale-looking Beyoncé driving a car in the dark, and this set-up did not appear in “Halo.”

The next year, a very different cut would leak online that both explained the driving footage and told a much darker story: Ealy’s character is being tracked through the forest by a bunch of men (who may or may not be police, based on their costuming) and at least one vicious dog. Beyoncé eventually arrives at Ealy’s location and finds him lying on the ground, the dog having killed him. It seems, then, that the airy, serene footage in the official cut is actually Beyoncé fondly remembering her lost love; she can see his halo because he’s an angel, which is to say deceased. This original version may not have quite come together the way the team hoped, or maybe it was deemed too dark or even inappropriate given the national mood. (“Halo” had premiered a month prior to the inauguration.)

When we get to the segment in Behind the Scenes: The Videos about “Ego,” which Beyoncé co-directed with Gatson—there were multiple versions, including an original, a remix with Kanye West, and one where Beyoncé sits instead of dances—she tells us, “‘Ego’ is where I made my directorial debut.” Though we know that she’d co-directed the new entries in her B’Day anthology in 2007, pop stars who get into directing often do this kind of record-revising and -resetting, for reasons probably case-specific to each one. It’s possible that Beyoncé felt she’d done more work on “Ego” than any of those earlier videos, and it’s also possible that she had newfound reasons to lay directorial claim to this work in 2009; in 2007, she was not yet the same sort of global icon who produced motion pictures, and whose brand seemed to be getting more cinematic with each passing week. (She’ll make another “directorial debut” later in this chapter.)

Interestingly, the last few minutes of the featurette are devoted to something entirely unrelated to I Am… Sasha Fierce: Beyoncé performing during Barack Obama’s inauguration festivities. “I think my biggest payoff in my career was singing for the first African American president,” she narrates while we see footage of her carrying Julez—still little, but bigger than he’d been in the studio while his aunt recorded B’Day (2006)—around Washington, D.C. “This is why I work. This is why I’ve sacrified everything: for these opportunities.”

Though this was a very different example from Walmart Soundcheck, Beyoncé had again found herself excited to commit recent footage to a documentary, but lacking a venue more sensible than a making-of short about the videos from I Am… Sasha Fierce. Girl, just make a feature!

Days after the video album’s release, superstar Michael Jackson died of an overdose of drugs administered by his doctor (who’d later be sentenced to four years in prison). No matter your level of fandom, the world seemed to stop at the loss of the otherworldly, complicated legend. Beyoncé, for her part, was filmed weeping onstage during her tour that summer, the “Halo” segment having partly become a Jackson tribute.

The superstar’s death would still be hanging over pop culture at the VMAs in September, where “Single Ladies” was nominated for nine awards (including all six of the non-fan-voted craft ones). The show began with a longer tribute to him that featured both Madonna and Janet Jackson, beginning things on a dance-y but somber note. The VMAs crew was sure to grab a reaction shot of 28-year-old Beyoncé, one of the most vocal MJ admirers in the business.

From there, it seems to have been constant emotional whiplash for her. The first award of the night was Best Female Video, a fan-voted award that she lost to 19-year-old Taylor Swift for “You Belong With Me” (2009). It was then that a drunk Kanye interrupted Swift’s acceptance speech to declare Beyoncé’s video “one of the best … of all time,” leaving both women crying backstage. Later in the evening, Beyoncé would win Video of the Year (another fan-voted award) for the first of only two times in her entire career, but her speech was donated to Swift so that the rising star could finish her halted one.

Even for a show famous for chaos, the 2009 VMAs were uniquely batshit; that was also the night that Jay-Z saw his “Empire State of Mind” performance crashed by Lil Mama, and that relative newcomer Lady Gaga staged her own bloody demise during a performance of “Paparazzi.”

In the midst of all of this, there was something about the death of MTV icon Jackson that felt like the end of an era, or even like there was a changing of the guard afoot. While Gaga—another devotee of the late superstar—had certainly used the network to her advantage (as she did that evening), she was an artist who made MTV feel somewhat incidental to her rise, becoming best-known for making provocative, profane, sometimes disturbing videos and then simply premiering them online. And funny enough, there was really just one artist who’d spent the year wearing a single glove and performing Fosse-inspired choreography while fans cried and fainted around them, and that was Beyoncé. When she performed “Single Ladies” during the same VMAs, she wasn’t exactly tributing Jackson the way the rest of the room was (though aspects of the live arrangement seemed to nod to him); she’d long ago begun taking his teachings into the future.

With the exception of the Lil Mama thing, each of these bits of chaos—the death of Jackson, Gaga’s “Paparazzi” performance, and even Swift v. West—would have some sort of implication, in their own weird way, for Beyoncé the visual artist. There was something about Jackson’s video-making ethos that she didn’t want to see disappear with him. There was something about Gaga’s freaky-sexy hold over the room that she seemed to want in on. And there was even something about Kanye’s interruption that expedited artistic comparisons between Beyoncé and Taylor Swift.

The next month, Beyoncé was presented with Billboard’s 2009 Woman of the Year honour, thanking her parents in a quick speech before being interviewed onstage by Gayle King. She also crossed paths yet again with Lady Gaga, an idea starting to snowball in her head.

To coincide with this annual Women in Music event, Billboard ran a Q&A with Beyoncé that had been conducted in September, again paying notable attention to her screen career. “All of the work I’ve put into my films has paid off because the type of scripts I’m getting now has completely changed,” she said. “I’ve always wanted to do something darker and more dramatic because I’m much better at drama than anything else. I don’t think anyone knew that until I played Etta James.” She also mentioned how fun she’d found “doing those stunts” on Obsessed, and reminded readers of her interest in something more action-heavy.

But she then took things a step further, adding:

I also want to continue to produce films—even if I’m not in them—as well as a documentary on my life. Actually, I’d like to do a film loosely based on my father’s childhood and school years. He’s had an interesting life. But that will probably be in a couple of years.

The star had finally arrived at the idea of an autobiographical feature, thank God. But we’ll put that aside for a second, since it’s the other revelation that fascinates in hindsight.

Beyoncé’s instincts as a producer here were pretty bang-on, however challenging a film about her father’s early life would have been to see through. Born in 1952 in segregated Alabama, Mathew’s childhood was spent avoiding run-ins with the Ku Klux Klan and facing constant violence and dehumanization as he helped integrate various all-white schools. (Years later, he’d publish a memoir about all of this called Racism from the Eyes of a Child [2017].)

But the very same day that Billboard ran the Q&A—that Beyoncé had stood onstage thanking her parents for helping her build this spectacular career—TMZ reported that Mathew had been served with a paternity suit by a woman named Alexsandra Wright. In J. Randy Taraborrelli’s fascinating but flawed biography, Becoming Beyoncé (2015), in which Wright is quoted extensively, she claims that Mathew was actually handed the papers at the Billboard event.

On Halloween, Channel 4 in the UK aired a special called Beyoncé: For the Record (2009), another interview from September where Steve Jones had flown to Australia for a sit-down with the star. The director of the special was Tim Van Someren, an accomplished player in the live space, so it wasn’t exactly a project released by Beyoncé HQ. As with Walmart Soundcheck, however, much of it rests on her own documentary footage, and Burke is credited as “Additional Concert Footage Videographer.” (Other future members of the Parkwood team also appear in the credits.)

The main reason I mention the special, though, is the heightened focus on filmmaking; as with the Vogue cover story and Billboard Q&A, that’s one of the main things Beyoncé seemed to want to talk to journalists about in 2009. For instance, Jones asks the star whether she ever feels like she lost an element of her childhood doing all that work. “There were certain moments,” she admits. “I didn’t have as many friends. But thank God I started making movies and being around the same people for six months at a time, and I was able to still experience some type of… that was like my college.”

Eventually, she says:

I directed a music video and I’ve always been really involved with the production on my shows. I love all of that stuff. So I would love to eventually … direct music videos, and eventually direct maybe some films. I want to do a documentary soon. And I’d like to maybe start my own label, and start looking for other talent … I don’t know if I want to manage. But if anything, I am a really good teacher and I know a lot of things about performing, and I would love to just help new artists and young artists.

Beyoncé had again undersold the work she’d already done on the production side of things. Aside from the fact that she’d directed more videos than just “Ego,” she was truthfully weeks away from releasing her first self-directed documentary short. So what’s interesting about this quote is not just Beyoncé’s big directing plans for the future; it’s that she’d actually been directing behind the scenes, but was now starting to actively weave that into her public image.

What also makes the quote interesting, of course, is that it was delivered in late 2009—a full year and a half before the star would officially lift the kickstand on Parkwood Entertainment. “I’m still my father’s baby girl,” she explains in the chat:

I’m a very strong businesswoman. And when it comes to my art and it comes to my shows, I know every little detail and I’m very much in control. And I think, you know, it took a couple of years for my father to understand that … It’s something that we still struggle with at times.

It seems, then, that Beyoncé was conceptualizing what later became her own company long before her existing management started to create certain PR headaches for her. The Billboard event hadn’t even happened at the time of her sit-down with Jones, but here she was publicly planting seeds that her current arrangement had some room for improvement.

A more fun development of the Billboard event was that Beyoncé had decided she wanted to collaborate somehow with Lady Gaga. In September, she’d released the eighth single from I Am… Sasha Fierce, “Video Phone,” but subsequently recalled it so that it could be turned into a remix featuring her new friend.

In “Video Phone,” Sasha Fierce (subtextually) offers to live as spank-bank material in a suitor’s cellular device. Immortalizing someone onscreen is apparently her love language, and the feminist twist is that she wants footage of him, too. “You should let me put you in my movies,” she sings in the second verse, promising to “turn [him] into a star.”

The remix largely replaces this verse with a new one from Gaga, dialling up the sense of capital-C Cinema:

Hubba, hubba

Honey, baby is so sexy that he should win an Oscar

And when you miss me

Just remember that I always got you with me

I’ll be your Gene, you’ll be my Brando

I’ma put you in my movie if you think that you can handle

Gaga was another artist with a unique relationship to the film world, one that deserves its own long-form project. But for about half a year beginning with “Video Phone,” she and Beyoncé maximized their joint slay as cinephilic pop stars. Aside from the new verse, the remix begins with 50 seconds of totally new audio, teasing the original’s crunk beat but mixing it with what sounds like the score for a spaghetti Western.

In the Hype Williams-directed video for the remix, Beyoncé spends these seconds imagining Sasha Fierce as a de facto Quentin Tarantino character, recreating the opening of Reservoir Dogs (1992) with a group of men. The rest of the video is mostly her being evil-hot in various looks and set-ups, wielding cartoony weapons and even appearing to have some hostages. Gaga shows up about halfway through for her verse and a dance, doing her best with Beyoncé-tailored choreography that she’d learned the day prior.

“That’s what’s fun, though,” Gaga says in the official making-of segment, cracking up while watching back footage: “We can trade.”

And so we arrive at another Thanksgiving—which, as a reminder from the previous chapter, Beyoncé reliably took as an opening to release a long-form visual project for years.

True to masochistic form, she’d chosen to use a two-week break that she and her team had in the summer—just after the North American leg of her tour, but before it moved over to Japan—to perform an entirely different show: I Am… Yours, a jazzy four-night residency at Wynn Las Vegas. In the end, those performances wrought two different films, which Beyoncé combined into a single special for ABC. (They came separately on the DVD that followed.)

The first was the concert film of the residency, I Am… Yours: An Intimate Performance at Wynn Las Vegas (2009), directed by Nick Wickham of The Beyoncé Experience Live (2007). The star spends the first half of the show singing Vegas-y takes on her catalogue, mostly I Am… Sasha Fierce, and even doing some scatting. She then uses the second half to tell a song-and-dance version of her career story, from auditioning for her first record deal (“I Wanna Be Where You Are”) to recording B’Day in the aftermath of Dreamgirls (“Get Me Bodied”).

I Am… Yours is an underrated concert film of Beyoncé’s, evidence of her strikingness as a performer even without the usual bells and whistles, and a prime example of how she’s often breathed new life into her discography through inspired live-arranging. The bulk of the focus is kept on the music and perhaps lighting, with only the storytime half choreographed in the traditional sense. Included in that is what appears to be a new Bob Fosse reference, this time to the chair staging of the “Mein Herr” scene from Cabaret (1972). (She’d been doing something similar all year on the I Am… World Tour.)

The film is also an excellent showcase of Beyoncé in mythmaking mode, since she literally narrativizes her career. Along the way, she embellishes and she omits: Austin Powers in Goldmember (2002) becomes her first movie; her label is nervous about the hit potential of Dangerously in Love (2003) not because “Work It Out” flopped in the US but because they’re going out of their way to doubt her; and the story conveniently ends three years early, which means that she doesn’t have to include her wedding.

“One day, I woke up and said, ‘I got it. I’m gonna tell my story,’” she explains in the second project included on the DVD, a documentary called What Happens in Vegas (2009). The 25-minute film was co-directed by Beyoncé and Ed Burke, marking the first non-music video project on which Beyoncé ever had a directorial credit. We see how her team is using their soundchecks on the I Am… World Tour to put a whole other show together, and we feel everyone’s stress as opening night approaches and it isn’t ready to have an audience.

While previous documentaries had given us glimpses of tension between the star and, say, the VMAs crew, this was the clearest look we’d gotten of her being exacting and even annoyed with her own team. We’ll be coming back to that a little later, but for now: there was an uptick in what you might call Shadiest/Diva Moments as Beyoncé began directing her own making-of content. In a film career that’s been defined by careful brand management and sometimes caginess about her personal life, her industriousness and authorship have instead always been played up. She could insist to however many interviewers she wanted that she was the main driver of her career—as she’d noticeably started doing around B’Day—but it was another thing to have hard evidence.

Despite anything that may have been happening with the Knowleses, the film wisely includes a quick cameo from Mathew as he checks in on rehearsals back in August. At the same time, the appearance is so brief that he can’t realistically be playing any kind of creative role in this show. So at least as far as his daughter was representing him onscreen, he’d become ancillary to her whole operation.

Before 2009 came to a close, the women of the Knowles family filed two important documents. Ms. Tina filed for divorce. Beyoncé filed for the trademark for Parkwood Pictures.

In the new year, the star announced that she’d be taking a bit of a work break after the Grammys in January and conclusion of the I Am… World Tour in March. She’d wind up cancelling her final two shows without explanation, ending things a whole month earlier, and wouldn’t even wait that long to figuratively murder Sasha Fierce: “I have used this person to take over when I’m too scared or too shy. The thing that’s interesting is I don’t need Sasha Fierce anymore, because I’ve grown, and I’m now able to merge the two. I want people to see me.”

Officially, this hiatus was being prompted by burnout, both physical and spiritual. “I’ve always worked hard, but I feel like I worked harder this past year than I have since I was just starting out,” Beyoncé said. And in fairness to her, she’d already spent two years of her life with I Am… Sasha Fierce. Unofficially, of course, there was everything going on with her family. We’d also learn in time that she and her husband experienced the first of multiple pregnancy losses somewhere around here. She clearly just needed a little R&R.

Among Beyoncé’s efforts to nicely set up her hiatus, she was interviewed by Steve Kroft for a 60 Minutes segment that aired the same day as the Grammys—where, in addition to being the most-nominated artist of the evening, she set a new record for the most wins by a woman in a single ceremony (six). As far as we’re concerned, the segment is interesting for two reasons.

First, it stresses that it was Beyoncé who ran her world. “While her career is still managed by her father, Beyoncé is the steam that drives the engine of this huge enterprise,” Kroft narrates. When we see footage of her wiping out in rehearsals for “Single Ladies,” he continues:

This rehearsal was shot by her private videographer, who records many of her offstage activities for documentaries and DVDs. She is very much the custodian of her own image, and this allows her to guard her privacy, keep outside camera crews and paparazzi at a distance, and control content for her own commercial use.

In addition to this quote actually acknowledging the existence of Ed Burke, a figure so low-key that most fans wouldn’t be able to pick him out of a lineup, it connects a few dots that it would take most people many more years to: that the videographer’s hiring led to self-produced movies, and self-produced movies led to control.

The second interesting thing is how the interview credits this desire for control in part to Barbra Streisand. Kroft himself argues off the top that Beyoncé is “well on her way to becoming the Judy Garland or Barbra Streisand of her generation,” quite the compliment for a star who grew up admiring both women. (We’ll get into Garland later.) But Beyoncé again indicates that Streisand—“another singer-turned-actress and director,” as Kroft says—was someone whose career she was openly modelling her own after. “I know that she does everything, and I know that it’s all Barbra Streisand,” she explains. “It’s not someone that’s telling her what to do, what to wear, what to sing. It’s her, and I respect those [types] of artists.”

Streisand is a performer known for various projects, including films, where she proudly wore many hats; Yentl (1983), for instance, was co-written, produced, acted, directed, and soundtracked by Babs herself. Beyoncé, someone who’d later release enough projects in such a vein that she now jokes about it in her merchandise, clearly found this sort of thing aspirational rather than vain. As Kayleigh Donaldson recently wrote in an essay on Streisand’s directing, “[Her] work as a filmmaker is still frequently dismissed as a mere vanity project. Her music remains at the forefront of what fans love and expect from her, even as she has insisted for decades that she is more an actor and storyteller than a singer.” Though it would probably be wrong to call Beyoncé’s future self-directed films similar to Streisand’s, they too would sometimes be criticized as vanity projects.

Even without the tour, Beyoncé had several commitments to follow through on before she could officially clock out. One was opening an eponymous cosmetology training program at the Phoenix House in Brooklyn where she’d done Cadillac Records research. Another was filming the ten-minute video for “Telephone” (2010), the other half of the “trade” she’d made with Lady Gaga in the fall—this collaboration having appeared on Gaga’s The Fame Monster (2009).

“Telephone” was only really linked to “Video Phone” by its Tarantino references and Beyoncé’s Bettie Page wig. It was more obviously the sequel to “Paparazzi” (2009), a similarly long video that had ended with Gaga murdering her boyfriend and then calling the cops on herself so that she could be perp-walked in her choice of couture. “Paparazzi” had been Gaga’s first time working with Jonas Åkerlund, a director who’d appeared on the MTV scene around the same time as Beyoncé, quickly becoming a go-to collaborator of Madonna’s due to their shared knack for button-pushing.

Åkerlund was called back for “Telephone,” where Beyoncé (playing a character named Honey B) picks Gaga up from prison so that they can mass-murder a diner full of people. The iconography here drew vaguely from Tarantino’s work as well as Ridley Scott’s Thelma & Louise (1991), at one point recreating the shot where the titular women clasp hands before driving off together. (In an important twist, though, the video ends on a literal “To be continued…” note rather than having them die.)

Over lunch with Gaga, Tarantino himself had lent her and Beyoncé the Pussy Wagon from his Kill Bill films—making the video feel more like a tribute proper, but also saving them from having to use a convertible hearse.

“When I put on the Bettie Page wig, I got into the character,” Beyoncé would say. “I started researching Bettie Page and tried to channel her pinups and poses.” Though best known as a model, Page also appeared in a number of films throughout her career, mostly of the sexploitation variety and for director Irving Klaw.

By all accounts, Beyoncé did not have much creative involvement in the “Telephone” video relative to Gaga; she seems to have tackled her scenes at lightning speed that January, and has only sparingly acknowledged the collaboration since. Which is not to suggest that she didn’t realize she was participating in a project defined by its queer subtext and potential nods to prison porn, just that it could all be blamed on the corrupting influence of Gaga if necessary.

There was a sense that the straight-A student had befriended the new girl who liked to smoke up behind the bleachers, and the video itself had some fun with that: Beyoncé is the designated driver who scolds Gaga—the one who does all the poisoning and stranger-kissing—for being a “very, very, bad, bad girl,” and while both characters utter the word “motherfucker,” it’s only Beyoncé whose swearing is bleeped out (and who coyly covers her mouth afterwards).

“It was sort of a pop-art venture for me to bring her into my world,” Gaga would say. “It was something for me to kind of change the way that you see her for one video.” One clue as to how much Beyoncé enjoyed that experience is the number of times she’s hired Åkerlund since—but more on that in the next chapter.

On the fourth (!) of February, Alexsandra Wright gave birth to a baby boy, whom she named Nixon. Two weeks after the “Telephone” video premiered in March, TMZ reported that a DNA test confirmed Nixon was indeed Beyoncé’s half-brother.

Various sources, including a piece she’d write for Essence, have painted a picture of what the star got up to on her quote-unquote year off—consuming art of all kinds, being an aunt, visiting cities she’d only experienced out of the windows of cars and hotels. She spent more than a month just in Australia, eventually remembering:

It was a carefree existence for me. Next on my personal world tour was Japan, where it was my idea to go unrecognized as a Harajuku girl … to a couple of Tokyo clubs. In London I met Sade … In Paris my nephew Julez and I had escargot for lunch and it was actually tasty (though not as good as a funnel cake at the Houston Rodeo).

“In the end, my year off was more like nine months,” she’d admit, but even that might be a stretch given how much work she did in 2010; she was on the Coachella stage in the spring, giving interviews in the summer, and making surprise TV appearances in the fall. We’d later learn that she’d started recording new music as early as May, the same month that she released a video for “Why Don’t You Love Me” (2010), a bonus track from I Am… Sasha Fierce.

“Why Don’t You Love Me” was a relatively bare-bones affair where Beyoncé—co-directing with Melina Matsoukas, by this point a friend as much as a collaborator—poked some fun at the idea that she was supposedly taking time away to be a domestic goddess. Playing another new character called B.B. Homemaker, the video portrays her as a sexy but ditzy housewife, overwatering the plants and burning the roast. “I was still thinking about Bettie Page, and wanted to do something that was inspired by her,” she’d explain:

The video was a secret: I paid for and codirected it and didn’t tell my label or my management. The clothes and jewelry are from my closet, the wigs are mine, and I did my own makeup. We did eight looks in one day in this great house that belonged to a producer who worked with Dorothy Dandridge. He had pictures of her on the wall, so her spirit is in the video, too. I wanted Super 8 film and wanted to get those saturated colors. It’s a different drama—the tears and martinis and cigarettes. I wanted to channel the past for the present.

What Beyoncé doesn’t say here is that the video directly recreates several moments from Page’s sexploitation film work, including some of the shorter-form fetish stuff she and Irving Klaw used to make based on client commissions. (Here’s a handy edit.)

From the sexual overtones to the fact that the star had again loudly orchestrated a project behind her father’s back—the difference now being that the world was also seeing the headlines about his off-duty antics—something was clearly shifting at Beyoncé HQ. But I’d argue that “Why Don’t You Love Me” was also a signal moment for anyone following her evolution as a visual artist. Not only was she a year and a half removed from the release of I Am… Sasha Fierce, but she was also supposed to be on vacation; this was something she’d done purely for love of her craft, apparently needing little else but a buddy and some equipment to pull it off. And the implications of that were legion.

That Beyoncé struggled to take a vacation in 2010 came back to more than just willpower. Mathew’s own court filings would later reveal that in October, a law firm conducted an audit of him on his daughter’s orders. Apparently, Live Nation had told her that he’d “stolen money from Beyoncé on her most recent tour or otherwise taken funds that [he] was not entitled to.”

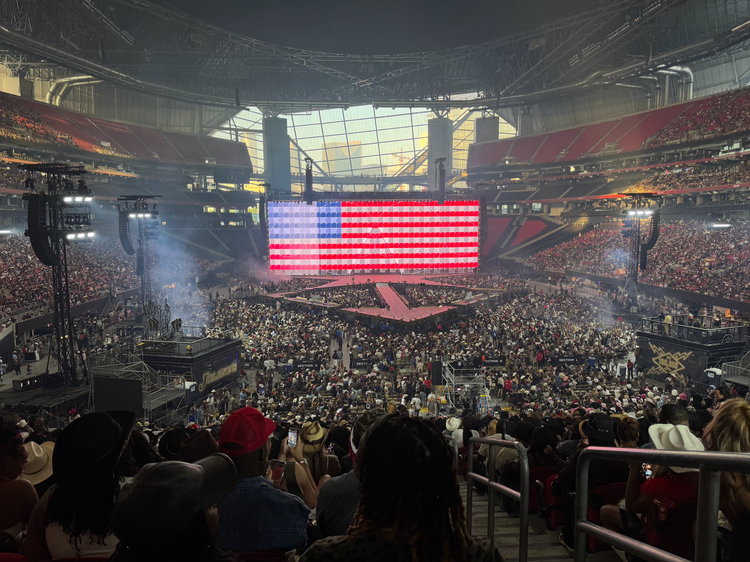

The next month, Beyoncé announced a new concert film called I Am… World Tour (2010), which she’d co-directed alongside Ed Burke and Frank Gatson—the first feature-length collaboration between Beyoncé and Burke as a directing duo, and the star’s first directorial credit on a feature, period. The press release noted that the film was being co-released, as usual, by Mathew’s Music World Entertainment. At the same time, it emphasized having been “produced, directed and edited by Beyoncé for her own Parkwood Pictures.”

In case “edited by” raises any brows, that messaging has remained consistent for a decade and a half; Beyoncé is credited as an editor on the film alongside Burke and Frederic T. Brehm. “I was very interested in filmmaking,” she recalled of this time in her life in 2021. “I learned how to edit the cut myself in Final Cut Pro, and it was the beginning of a newfound love and creative expression.” When a version of the film aired on ABC over—you guessed it—Thanksgiving in 2010, there was footage of her glam squad attempting to doll her up while she worked in the edit bay.

I Am… World Tour would be the final feature to come out of Parkwood under the name Parkwood Pictures, but it was arguably the start of many more things. The concert film cuts together multiple shows from the tour, actually labelling certain shots with their location and show number. As the New York Times wrote in its review of the special, half of which was turned over to Taylor Swift also having a Thanksgiving special: “The documentary quietly flaunted her consistency as a trouper in montages that segued multiple shows—supertitled in small type—with Beyoncé in the same outfit making the same moves, while the fans’ nationalities changed around her.” It was as if you took the “Man in the Mirror” opening of Michael Jackson’s Moonwalker (1988), a film I’ve mentioned previously, and stretched it out for an hour and a half.

“This is my directorial debut,” Beyoncé told Extra at the premiere, which was true if we’re talking features. “The directing was really in the edit; it took me nine months to edit because I wanted to show a little bit of each show.” In other words, the star was perhaps the worst vacationer of all time.

If there’s a select group of popular musicians who’ve directed feature films, the group who’ve self-directed concert films (to say nothing of directing multiple) is considerably smaller. But the choice was at least partly explained by the wealth of personal footage woven throughout I Am… World Tour, much of it shot—in Beyoncé’s words—“in my little Mac computer, the same computer everyone iChats in.” Indeed, the film suggested that the “Why did God give me this life?” monologue we discussed last time, seemingly delivered on her 26th birthday in 2007, was just one of many vlogs that existed on her hard drive. There’s so much of this kind of material in the film that the star, alongside Burke, is credited as having provided “Additional Photography.”

Ten minutes into the show, we’re suddenly pulled out of the arena and into the star’s bed in New York City, where she’s recording a video diary dated March 25, 2009—the day before the tour began. “I’m in my favourite place in the world right now, which is my home,” she says, seemingly wearing nothing but a duvet. “Tomorrow, I am Sasha Fierce, and it’s no turning back. But I think I’m gonna be gone so long, it might be wise to start being Sasha Fierce”—and here, she flashes a mischievous look at us—“tonight.” Once again, there was a feeling in 2010 that her star persona was growing up a little. (We move from here right into “Freakum Dress.”)

While promoting the film, Beyoncé shared a story about feeling lonely one day in her hotel room in China, explaining, “I wanted to talk to someone so I opened up my computer and I just talked.” But the moment of her at home in bed indicated that she didn’t have to be starved for companionship to record this kind of thing; maybe, just maybe, she was already thinking ahead to the film she’d make a year and a half later. Either way, it’s understandable that she wanted final cut over material so intimate. “It’s a lot of things I reveal about myself that I could never give to [another] director,” she said, saying elsewhere, “I would never have gotten so open if someone else was in the room.”

Unlike any concert film Beyoncé had made previously, this one relied heavily on doc footage of all kinds, and that was at least partly because doc footage had been built into the stage show in interesting ways—taking things up several notches from what we’d seen in The Beyoncé Experience Live. Towards the end of “Halo,” just before Beyoncé begins addressing the song to the late Michael Jackson, a home video of her heading out the door for a concert of his (the same one that had appeared in Beyoncé: The Ultimate Performer [2006]) plays behind her. During “Radio,” half of the jumbotron is occupied by a similarly tiny Beyoncé getting her groove on so that the 20-something star can dance with her childhood self.

But we’re more generally removed from the show all the time for quick doc stretches. During “Ego,” we spend a lot of the song not onstage with Beyoncé but in dance rehearsals for the tour. As “Halo” wraps up, the film gives us the group prayer from the July 13, 2009 show at the Staples Center—where Jackson had been rehearsing in the hours before he died, and where his memorial service had taken place days prior.

When it comes to this non-show material, a lot of fun was clearly had in the editing room. “I think because I don’t really know that much about the technical aspect, I took a lot of risks in the edit,” Beyoncé said. The film will give us a shot of Solange sitting in the audience at her sister’s show, and then we’ll cut to footage of baby Solange in a home video. There’s also a segment where the star is swarmed by people as she tries to go shopping in France, telling Burke’s camera, “[It’s] kind of like being in a fishbowl. And sometimes it feels like I have to walk with a permanent smile on my face because if I’m just normal and I just look around, then somebody might mistake me for a mean person.” Across the room, a self-described superfan then tells Burke that she’s a “bitch” for not looking at him in the Prada store. “She probably didn’t hear, she probably didn—” we hear the videographer start to respond before he’s interrupted: “She’s probably a bitch.”