When MTV Was Still Finding Its Footing

This is the first of a three-part series tied to the 40th anniversary of MTV's launch, in which I use things from the archives to delve into various chapters in the network's history. Here, we look at a post-launch but pre-explosion MTV.

August 1, several Sundays ago because I’m currently in my dipshit era, officially marked 40 years of Music Television, aka MTV. You wouldn’t know it from tuning in to the channel itself that weekend, where you could catch episodes of *checks notes* Ridiculousness, Ridiculousness, or Ridiculousness (a show that I’m not sure I’ve ever seen a whole episode of). “happy August 1 to @taylorswift13 and @jackantonoff only,” tweeted the MTV News account, in reference to the song “august” from Taylor's folklore (2020). The network did introduce a reimagined Moon Person (formerly Moonman, the award that’s handed out each year during the VMAs) designed by Kehinde Wiley—he did the official portrait of Barack Obama a few years ago—but this happens to be the third such reimagining of the statue in a decade. In other words, MTV didn’t really do anything special for the anniversary.

The network’s logic here, which came to light around the time of its half-assed 30th anniversary celebrations a decade ago, is that its main target audience—today's young adults—doesn’t really care to rehash the year 1981. “MTV as a brand doesn’t age with our viewers,” explained Nathaniel Brown, then an MTV executive, in 2011. “We are really focused on our current viewers, and our feeling was that our anniversary wasn’t something that would be meaningful to them, many of whom weren’t even alive in 1981.” The history of MTV is really a list of identity crises and subsequent reinventions to keep up with the times, and while that’s true of just about any television network, MTV is perhaps uniquely plagued by complaints about that list.

Only time will tell whether there’s anything interesting planned for this year’s VMAs broadcast, scheduled for September 12. But in the meantime, I’ll be sending out three different things this week—sorry that they’re so squished together, and new subscribers should know that this is unusual; again, in my dipshit era—to commemorate the milestone. After all, while I understand Brown’s above sentiment from a business perspective, anyone reading this newsletter probably finds the anniversary at least somewhat meaningful. Each piece should look slightly different in practice, but they’ll generally serve as snapshots of three different moments in the network’s history; I’ll let them be a surprise as they show up. So, without further ado: “Ladies and gentlemen, rock and roll.”

Earlier this summer, I stumbled across a video on YouTube called “The Very First Two Hours of MTV.” It’s exactly what it sounds like, though it’s actually more like two and a half hours, where a couple segments featuring April Wine and Cliff Richard have been removed due to copyright claims. “I really tried to get them to understand that this was an historical archive, *not* an attempt to steal money from their band,” writes uploader Max Speedster in the description. “They didn’t want to hear it.” Speedster’s channel consists of—to quote from their own About page—“mostly random stuff from my hard drive,” and this is the second most-watched video among the miscellany.

Aside from the missing segments, everything else appears intact: there’s a funny slew of circa-1981 ads—for Superman II, for Mountain Dew, for Chewels sugarless gum. The cast of M*A*S*H shows up for a leukemia PSA. We get a couple early prototype segments for what would eventually become MTV News: Ramones are in town! Talking Heads are pursuing solo projects! And then in terms of the videos themselves, we get two different ones from both Rod Stewart and the Pretenders, since they were among the many British artists who’d already hopped on the music video train to supply local music television programming. (There were also lots of Australians and New Zealanders making them already for the same reason.) We get two videos from REO Speedwagon, who belonged to the much smaller sliver of American artists making them by this point. I was surprised by how little of this music I knew overall, and that I’d only actually seen a couple of these videos before (out of roughly 30). And while that does speak to my age to some extent, it’s equally relevant that the MTV rocket wouldn’t really take off for another couple of years, at which point it started to immortalize the decade’s music in earnest.

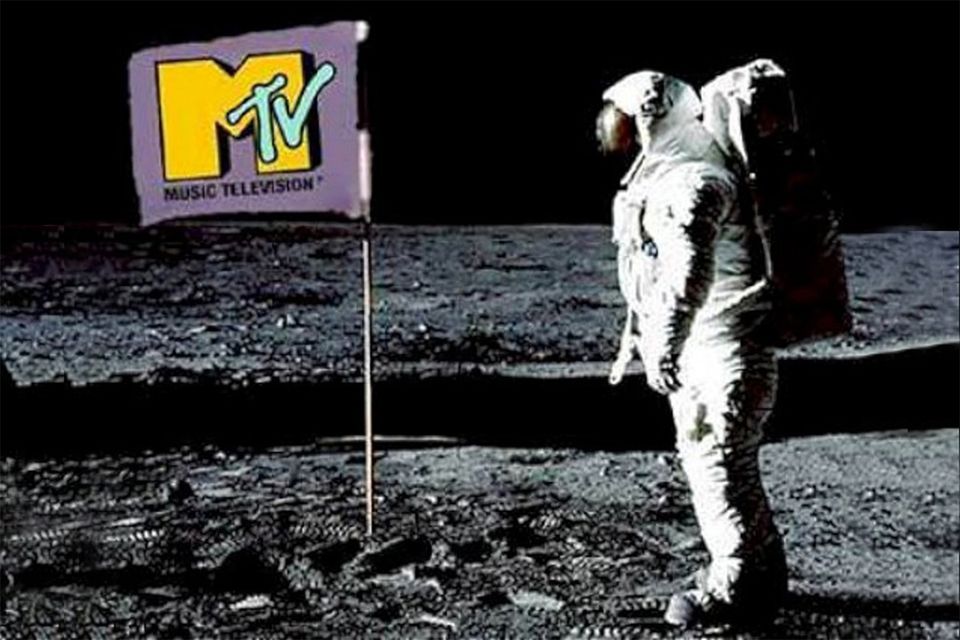

There are quite a few MTV broadcasts on YouTube, many of them flashier and perhaps more interesting. But I’ve hitched my wagon to this one for the unbridled ambition on display. The first video to ever play on the channel was, rather cheekily, the Buggles’ “Video Killed the Radio Star” (1979). (When the network launched in Europe six years later to the day, it kicked things off with Dire Straits’ “Money For Nothing” [1985], an equally cheeky choice.) We’re introduced to each of the network’s five original VJs, who keep telling us that we’ll “never look at music the same way again.” To repeat myself a bit, it would take a little while for MTV to explode the way that it’s now remembered for having exploded, so it’s fascinating in retrospect to see how the channel was hyping itself up from the jump. “MTV’s done for TV what FM did for radio,” VJ Mark Goodman tells us, MTV having existed for less than an hour.

I recently had all of this better contextualized for me by Biography: I Want My MTV (2019), the documentary directed by Patrick Waldrop and Tyler Measom. I highly recommend watching the film yourself at some point—and also checking out the 2011 book of the same name by Rob Tannenbaum and Craig Marks (both of whom appear in the film), which largely tells the same story in oral history form. Both texts are among my main sources for this series, so I’ll be coming back to them a lot.

I Want My MTV the film is mostly concerned with the first decade of the network, while the ‘90s and beyond are abbreviated in its last several minutes. The introduction of The Real World in 1992 is implied to have sounded the death knell for the network's original concept of non-stop music video television, but one thing I appreciate about the film is that it’s a lot more positive than one might expect about the 1992-present era. The hard truth is that ratings had significantly tapered off by the early ‘90s, and the network was forced to rethink its approach, as it’s had to do in each of the decades since. While some people—I don’t prefer to keep them around, but they do exist—love to say that music videos died when MTV moved away from playing them 24/7, the film emphatically and correctly nods to how much music videos have thrived since 1992, and obviously beyond the scope of the network. There’s the obligatory mention of OK Go’s “Here It Goes Again” (2006), representing the greater promise of YouTube for creators of all kinds, and additional shots from things like Kendrick Lamar’s “Alright” (2015) and Beyoncé’s Lemonade (2016). The overall tone here is actually pretty different from I Want My MTV the book, which at one point reads:

For us, 1992 marks the end of MTV’s Golden Era, which was brought to a close by a series of unrelated factors. Video budgets rose steeply, leading to wasteful displays; digital editing arrived, making it a snap for directors to flit between shots and angles; all the good ideas had been done; record labels increasingly interfered in video decisions; many of the best directors moved on to film; Madonna made "Body of Evidence." It’s also the year MTV debuted "The Real World," a franchise show that sped a move away from videos, the network’s founding mission, and into reality shows about kids in crisis, whether an unplanned pregnancy or a clogged toilet in the "Jersey Shore" house. "The Real World" was the culmination of the network’s initiative to create its own shows and was also the last time MTV could claim to be revolutionary. MTV created the music video industry, then abandoned it, leaving behind a trail of tears—disgruntled music-video fans have stamped the phrase “MTV sucks” and “Bring back music videos” all over the comments pages of YouTube.

As you might imagine, I agree with some of this but not all of it, and I’ll be wrestling with a lot of these same ideas throughout this series as I move out of the ‘80s. But it would be pointless to argue with the claim that MTV created the music video industry, or at least the music video industry as we know it. Indeed, while music videos certainly predated the channel, MTV made it more or less mandatory to make them if what you hoped to do was sell records. (As Heart’s Nancy Wilson points out in the film, however, the professional obligation to be a video artist in addition to a musician wasn't without its downsides: “Janis Joplin or Aretha Franklin wouldn’t have been an MTV star.”)

And although MTV wasn’t the first place to find music video programming, it was the first 24-hour music video channel—24 hours over which record labels could fight to figuratively sell their artists over someone else’s artists, week after week, year after year. (To state something potentially obvious here, music videos were being paid for by labels, in the hope that MTV—paying not a cent for this content—would show them to millions of people. This, naturally, drove competition among artists, which meant that it helped a lot to do something gimmicky and/or outlandish and/or expensive.) In terms of motivating you to visit a record store, it’s one thing to catch a print ad for Like a Virgin (1984), and quite another to watch Madonna work a gondola (and... also a lion) in “Like a Virgin” (1984). There were artists like Miss Ciccone who debuted ready-made for the MTV era, artists whose existing shticks made for smooth transitions into it (e.g. David Bowie), artists who needed a bit of persuading to make the jump but ultimately managed (e.g. Bruce Springsteen), artists who made a complete cock-up of it (e.g. Billy Squier), and artists who’d been given the comeback opportunity of a lifetime (e.g. Tina Turner).

There were also artists who were ready for MTV long before it was ready for them. One thing that stands out about the first two or so hours of the channel is how white everything is, which wasn’t exactly an accident. As Tannenbaum writes in the introduction to the book:

MTV’s programmers came from radio, where the trend was "narrowcasting," a way of targeting a specific demographic and selling your popularity within that audience to advertisers, rather than aiming for the largest possible audience. Broadcasting was Ed Sullivan creating a show that mixed the Beatles with a mouse puppet named Topo Gigio. Narrowcasting was embodied by MTV’s initial commitment to playing rock videos, which meant videos by white musicians.

That said, as is noted later in the book, “MTV aired videos by plenty of white artists who didn’t play rock.” Fixing this problem involved several different musicians, mostly Black ones, publicly calling the channel out. The examples given the most airtime in the film are Rick James, who accused MTV of racism on national television after he’d had multiple videos rejected, and Bowie, who took advantage of a 1983 interview with Goodman to light a fire under the channel's ass. “There seem to be a lot of Black artists making very good videos that I’m surprised aren’t used on MTV,” Bowie begins, and then lets Goodman do most of the talking—bungling things pretty quickly, since he inadvertently admits that MTV doesn’t want to aggravate the white Americans “that would be scared to death by Prince, which we’re playing, or a string of other Black faces.” (Goodman, for the record, says in the film that he considers the way he handled this moment the great regret of his life.) Not all that surprisingly, it seems to have been Bowie’s comment over the others that made the biggest waves internally at MTV.

The channel would eventually use Michael Jackson, who’d in some ways been making music videos since he was a child, as their solution. This story differs slightly from source to source, but here’s how the film tells it: MTV asked Jackson for a video for “Beat It” (1983), since it was Eddie Van Halen—someone closer to their idea of a rock star (though not white, it’s worth mentioning)—who did the guitar solo on that song. Jackson agreed, but then sent “Billie Jean” (1983) over instead. And while Jackson had pulled what’s referred to in the film as a classic bait-and-switch, it was simply too good not to play. Pretty soon thereafter came “Thriller” (1983), a video that shook the industry up at least a dozen ways, with MTV reaping many of the rewards for the remainder of the decade. “People say, ‘Oh my god, overnight it exploded,’” says co-founder John Sykes in the film. “You go, 'No, it didn’t happen overnight. It was four years of overnights.’”

Another relevant delay here, of course, had been the actual availability of the channel: you needed to have cable to watch it, and basic cable wasn’t the standard across the United States at the time of the 1981 launch. (“I want my MTV,” the slogan that came about in 1982, was literally the channel giving teenagers a line that they could use to bully their local cable providers into carrying it.) One funny illustration of this is that its co-founders, unable to access the channel in Manhattan, had to drive to New Jersey to watch the MTV rocket—in a rip-off of the Apollo 11 mission, but where it’s the MTV flag planted on the Moon—take off at midnight. And that’s exactly what makes these first two and a half hours of the channel so fascinating to me: the irreverence and the braggadocio somehow sitting comfortably alongside the terrible production quality and the often unimaginative videos and the practically non-existent viewership. What if the idea hadn’t worked? ●

Mononym Mythology is a newsletter about mostly pop divas and their (visual) antics. It’s totally free, but if you got something out of this instalment, consider buying me a coffee. The best way to support my work otherwise is by sharing it. You can subscribe here, and you can find me on Twitter and Instagram.