“Like Lightning, Indeed”

Somehow, this week marks three whole years of Mononym Mythology, the newsletter where I use my two film degrees to wax poetic about pop stars. However long you’ve been reading it, or even if you’re taking this as your reminder to unsubscribe, thanks for giving it a chance at all—and I mean that!

I’ve obviously opted to celebrate past special occasions with AMA sessions, but I found myself not especially wanting to do anything of the sort this year. I recently answered a bunch of questions of a similar nature for Film Cred, for one. But as this birthday was approaching, and as I was doing some reflecting on the past few years’ accomplishments—the music video careers synthesized, the authors interviewed, the publicists terrorized—I also got to thinking a bit about the idea of community. “Does this newsletter even have one of those?” the devil on my shoulder asked, to which the angel on my other shoulder replied, “That’s who you’re always getting your AMA questions from, dumbass.”

At which point it also occurred to me that June would be bringing Pride Month, and that there was a way of weaving all of these threads—plus some of the other ideas that have been rattling around in my brain as of late—together. A few weeks back, I put out a call to self-identified “friends of the newsletter” who fall somewhere under the LGBTQ+ umbrella. A number responded to that call, and then I sent those responders the following prompt.

“A quick preamble to the prompt: a big thing that brings me to my work in the first place is how certain music videos expanded my imagination/threw my brain curveballs/got me interested in various concepts and aesthetics at formative moments growing up. And I’m always curious to hear what such occasions looked like for others—the art that hit during a crucial stretch as far as their teenage hormones went, that unlocked a sudden realization, that helped them through a rougher period, that they were mesmerized by for reasons not immediately clear, that had them secretly replaying a particular stretch of a VHS tape or YouTube video, that they carried in the back of their mind for years and years, etc. And in this age of drag bans and book bans and other disillusioning/overwhelming reactionary bullshit, I guess I’m also thinking a lot lately about the art that you’re glad found you exactly when it did, in defiance of any forces that may have tried to prevent it from finding you.

And with that, the official prompt: tell me about a music video moment—or a screen-based music moment, if you’d prefer—where something shifted in your brain.”

Here’s what they sent back: a thoughtful and often quite moving collection of memories and other musings, and some fuel for me for the next three years.

Thanks so much again to each and every one of you, and Happy Pride! ●

Masooma Hussain — Writer, Songstress

Sade was the most beautiful mermaid I’d ever seen. I, an especially cognizant toddler, was transfixed by “No Ordinary Love” and its homage to my favourite movie, the one where Ariel willingly gave up her voice to be with the one who stole her heart. The animated version had a happy ending: four legs, wedding docked close to home, maybe plans to visit Atlantica on the holidays. This was the grown-up version. I had no idea what an “ordinary love” even was, but after this glimpse of the extraordinary, nothing else would do.

Mermaid Sade is graceful in her desperation, coolly flipping a magazine amidst the coral. Her lover (a sailor, though for the longest time I thought he was a mime) once plunged towards her, holding and kissing, swirling in the sea. She reminisces. She sews a wedding dress. It’s a two-piece! She wears it and walks (!) down a city street, throwing rice. She searches for the human who fell into her grotto, who showed her what could exist above the surface. She goes to an unfriendly diner and orders salt water. She can’t sustain this. She clutches her life-giving water bottle and runs, something a mermaid could only dream of, back to the sea where her fins will return.

Neither Sade nor Ariel could ultimately be a part of someone else’s world while remaining part of their own. A grown mermaid should know better, but I can’t fault her for trying when a love this extraordinary comes along.

Ade (aka the other Agent M)

What I keep on returning to is “Honey.” Before I knew that (people claimed) the lyrics were a euphemism for semen. Before, in an act of daring, aged seven, I would nearly drown trying to replicate Mariah’s diving scene in my apartment’s kiddie pool. Before all of that, I was a very little boy in Lagos, Nigeria, watching bootlegged American music videos with my older sister.

I can still recall that initial sense of amazement I felt watching Mariah (secret Agent M) dive from the balcony of a mansion and into a pool, emerging gracefully and continuing on her daring escape. It was beautiful, and I wanted to be her.

She was glamour. She was a Black Charlie’s Angel (my favourite film then).

As an adult, it’s easy for me to look back and think of that moment as indicative of a nascent queer gaze. After all, a young, dark-skinned Nigerian boy wanting to imitate Mariah Carey must mean something, right?

Maybe. Maybe not. What I do know is that I felt desire watching Mariah as Agent M. She led me to another world through the screen, and I was brave enough to reach out for it.

Kyle Turner — Critic & Author

The only thing to keep you sane in the overwhelming throng of gay people finding the groove in their heart, blinded by the colored lights, is a gigantic LCD screen projecting whatever music video accompanies the pumped-to-the-floor bass of the club’s soundtrack. The night I went to my first gay club as a newly out person, TigerHeat in L.A., the huge, glowing wall of light was an anchor. That night, you could see the handy work of Avicii and director Sebastian Ringler’s video for “Addicted to You” pierce through the twinky crowd, the queered Bonnie and Clyde riff more hypnotic than the floor teeming with young beauties. It felt epic to be swept up in the crowd with other gay people, but still have my eyes resting not on any of the boys, but the video playing behind them. We were all moving, finding the excitement in the air, the possibility pulsating through the room, all while Avicii and guest singer Audra Mae thrummed around us:

I’m addicted to you

Hooked on your love

Like a powerful drug

I can’t get enough of

The scope, the attention to detail, its smarty pants appropriation, felt like an opening up of possibility. I was addicted to it.

Ariana “Soda” Martinez — Film Critic & Culture Writer

My passion for film was born out of ‘80s music videos, a love gifted to me by my mother. Amongst her belongings was Madonna’s The Immaculate Collection on DVD. I’ll never forget showing up at my sister’s house to be babysat, the disc of videos my only toy. The first video on that DVD was none other than “Lucky Star.” I was probably 11 and found myself both mesmerized and repulsed by Madonna. With her piercing eyes, the intimate close-ups, and hardly any production design besides a white background, you have no choice but to indulge in her. Clad in all black, her body danced and stretched on the ground, rendering me uncomfortable at the site of her midriff, and I always stopped singing along at the line “Shine your heavenly body tonight.” Raised in a conservative, religious home, sex was not discussed, let alone attraction to the same sex. My kid brain had no idea how to respond to such “overt” sexuality. A woman slowly running her hands up her neck and through her hair?? Where is her mother?! But alas, in the same way time passed so my mother could share these videos with me, more time passed, and I grew older. By eighth grade, I was displaying my own midriff to my sister’s chagrin, and by junior year, I had my first girlfriend, who also liked to wear all-black ensembles. Starlight, star bright, make everything alright.

Claire Davidson — Freelance Entertainment Writer

2017 was a difficult year for me, a maelstrom of isolation and uncertainty in my life that caused me to become suicidal for a seemingly endless period. I know I wasn’t alone in these feelings, either: the fallout of Trump’s election had just begun, and the #MeToo movement had taken America by storm, exposing how deeply sexual predation is embedded in industries built on celebrity.

In the midst of these cataclysms came Kesha, who had emerged from a hiatus spurred by her lawsuit against producer Dr. Luke, whom she accused of, among several abuses, sexual assault. After having been dismissed as a casualty of the club boom, she was back with “Praying,” which flummoxed everyone in revealing that she was a genuine vocal talent. Even more astonishing was that, while the song admonished her assailant, it also expressed hope that he could find peace in coming to terms with the weight of what he forced her to endure.

I’m ashamed that it took “Praying” to make me a fan of Kesha’s, to see her discography for the gleefully anarchic collection of music it is. In a way, though, I’m grateful for the introduction, because the song’s music video—a colorful, cathartic Jonas Åkerlund collaboration—was a salve I desperately needed at the time. The opening monologue, in which Kesha, stranded on a raft, pleads with God to let her die, articulated a sense of pain that felt immensely intimate. Hearing that line, followed by the song to come, helped me understand that I could heal from my own deepest wounds, even if the process required tremendous strength.

I should note that the video has its flaws: the Hindi-inspired font that bookends the clip exemplifies Kesha’s career-long habit of cultural appropriation, a conversation about her work that has often seemed off-limits. Still, the video is riveting in displaying how multifaceted Kesha’s perspective on survival is, an approach encapsulated by the angel wings, crown of thorns, and ring spelling “LOVED” she wears as she plays piano, showing that even those whose triumphs seem divine are ultimately human. For all the rage, fear, and heartache expressed in “Praying,” Kesha still dons her signature motifs of glitter and gold throughout the video, indicative of her refusal to be cloistered by any one label or narrative, even after imbuing her art with the most personal truths.

Allison Driskill — Writer / Performer / Bisexual

As a music video, No Doubt’s 2001 clip for “Hey Baby” is nothing special. Scenes of the band partying are interspersed with green screen footage of them lip-syncing and goofing off together. But imagine you’re 11 years old and have never seen Gwen Stefani. This video becomes a foundational text. Gwen was simultaneously the height of glamor and the height of cool, pairing Old Hollywood makeup, pearls, and platinum blond victory rolls with low-slung houndstooth pants, a studded belt, and a bikini over a fishnet crop top. This, I realized, was the right way to be a woman. Try to be feminine, with your makeup bag, watching—but not participating in—all the sin, while still being “the kind of girl who hangs with the guys.” She was the perfect role model for a sheltered Catholic girl: beautiful but not slutty, successful but (allegedly) happily married, a larger-than-life persona but a tiny, toned body. In terms of women who have caused lasting damage to my psyche, Gwen Stefani is second only to my mother. I’ve done my stint as a platinum blonde, spent years in the ModCloth trenches emulating the “Cool” video, and finally realized I’m not comfortable in fully femme looks. At 32—Gwen’s age in the “Hey Baby” video!—I’ve landed on a balance that feels right for my queer identity: femme makeup and hair styling, often vintage-inspired, with masc clothing. The “Hey Baby” blueprint. No matter what they say, I’m still the same.

Zack Paslay — Writer

My memories start around 1998-1999, and the first few years of my life are informed by the sugary sweet pop that flooded the airwaves on Radio Disney. While acts of the time like Britney Spears, *NSYNC, and Christina Aguilera were in constant rotation, I was probably most obsessed with the A*Teens—the Swedish quartet that began as an ABBA tribute act. The group started their transition towards original music with their 2001 album, Teen Spirit.

The second single from that album, “Halfway Around the World,” held six-year-old me in a chokehold. Not only was the song a frenetic sonic wonderland, but the music video had a moment that kept me hoping it would play on the Disney Channel again. As the music video reaches the song’s bridge, we see the group’s members in different parts of the world. As the final chorus approaches, the group pushes down artificial barriers to show that they’re on a set and have been near each other the whole time before launching into group choreography.

As a kid who was already starting to obsess over how movies and music interact, this effect unlocked a part of my brain that hadn’t really thought about forced perspective and practical effects. The theatricality of the barrier push made me giddy, like a six-year-old’s equivalent to a drag queen’s wig reveal. It’s something that’s stuck with me for over 20 years, and it fed my fascination with music and film.

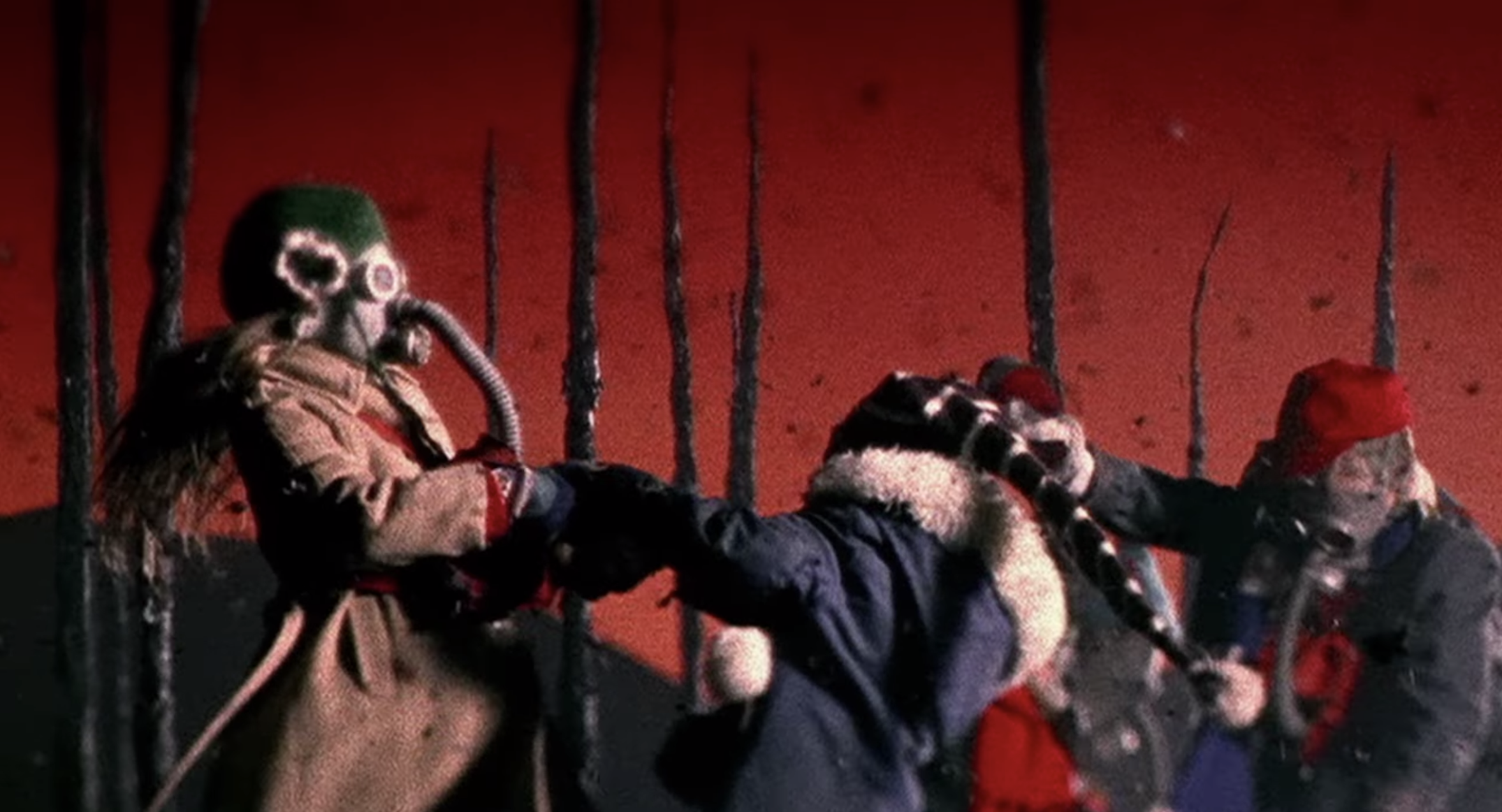

Aleš Kot — Writer / Producer

I could name so many but one of the first to come up for me is the Floria Sigismondi video for “Vaka” by Sigur Rós. I remember watching it with a group of other young adults late at night on some empathogens and such things and it hit everyone like a ton of very soft and very insistent bricks. I mean, it’s a video about climate change made in an era defined by intentional societal blindness to it. (Not that that era ended.) A climatological miniature Come and See/Threads, yet somehow also very tender. It shifted my brain because I gave in to it and let myself feel it even if it hurt. It reminded me to trust art. Both the patience of the opening and the final drop. You’ll feel it if/when you see it.

Em

In high school, after my parents’ divorce, I mostly wore black t-shirts and skinny jeans with big hoodies over top to hide my body, in an effort to disappear into the atmosphere. Every morning before school, I watched MuchMusic. Even though I was a classically insufferable teenager who thought I was above pop music (thankfully those days have passed! Life is too short to not enjoy such a wonderful and amorphous genre!), I remember 2008 when Metro Station and “Just Dance” played constantly on repeat.

The next year, Gaga dropped “Bad Romance” on her The Fame Monster EP. I was struck by Gaga’s theatrics, her sexuality (the first time I think I had ever seen a bisexual woman declare as much), her beautiful Alexander McQueen garb, and, of course, the desperation of her voice (“Je veux ton amour…I don’t wanna be friends!”). She saw herself as in a lineage of other prolific queer performers, she saw her pop as an art, a craft, an aesthetic to be built upon and experimented with over time. And so, I will love her forever!

Abdi Nazemian — Author / Screenwriter / Producer

I was seven years old when I saw Madonna’s “Lucky Star” video on MuchMusic in Toronto. In those few minutes of watching Madonna dancing, something inside me was awoken. I didn’t know until much later that the mysterious connection I felt to this woman’s energy was decidedly queer, and would lead me toward a community and a sense of belonging. All that would come later, after my Iranian parents had been badgered into taking me to the Virgin Tour and Blond Ambition Tour. But to this day, I’m fascinated by how I found myself obsessed with so many of our great queer icons before I had any concept of queer culture or even that being LGBTQ+ was something that existed in the world. The energy that can be transmitted through art is so powerful, and truly connects us to something bigger than ourselves.

Valerie Ettenhofer — TV Critic

When I was around five years old, I had Penelope Spheeris’s stoner comedy Wayne’s World memorized. I loved everything about it, from the gun rack bit that still floats to the tip of my tongue for no reason, to the silly product placement scene, which I acted out in my living room, Pepsi hat and all. I also loved Tia Carrere’s Cassandra. A gorgeous Cantonese-American aspiring rocker who was cooler, smarter, and more stylish than everyone else onscreen, she was easy to idolize and hard to forget.

All of Cassandra’s musical moments are dreamy and perfect in my mind, but none rock harder than her performance of Sweet’s “Ballroom Blitz.” Carrere takes to the makeshift stage in the Campbell family basement wearing a scarlet minidress and matching lace fingerless gloves. She has big hoop earrings and a big stage presence, and each and every time I watched the scene as a kid (sometimes while jumping on my couch, heartbeat in my ears), I felt like I was truly hearing music for the first time in my life.

It would be decades until I realized Cassandra was my first queer crush, but I knew at the time that her power and tenacity in this scene meant something major to me. It felt like possibility. I could wear lipstick. I could dress in red. I could even scream a song until my breath ran out and not care who liked it. Like lightning, indeed.

Erik Anderson — Founder/Editor-in-Chief, AwardsWatch

I’m going with a Madonna video, what a shocker. Madonna’s “Bad Girl” (1993) was a game changer for me, ten years into her music and video career. Her most cinematic video and the last of her four videos directed by the brilliant David Fincher just before his film career took off, this is Madonna the actress, Madonna the cinephile, Madonna the referencer as the video evokes both 1977’s Looking for Mr. Goodbar and 1987’s Wings of Desire in its story of a high-powered career woman living on a precipice of mortality.

Madonna’s videos are often short films unto themselves and “Bad Girl,” shot in widescreen (when so few music videos were at the time), the cinematography by Juan Ruiz Anchía, is a hazy, dreamy look at the morality and consequence of behavior as guardian angel/director Christopher Walken looks on. Madonna’s stripped-down but chic makeup look and long blond hair recalled the dramatic evolution of her style when the video for 1986’s “Live to Tell” was released, the artist constantly subverting her fans and critics alike.

It’s sort of wild that the video was shot as the release of her biggest critical and box-office flop, Body of Evidence, was rolling out in January 1993, and in some ways is a salve for that film’s knock-off quality. With David Fincher always able to get such a good performance out of the star, it’s too bad they never worked on a feature film together.

Nicoleta — Music Video Lover

The music video for Beyoncé’s “Green Light” mesmerized me. I would’ve been 12 when this came out, and didn’t speak English, so visuals truly embedded themselves deep into my psyche. Lots of music videos featured gorgeous women, and at that age you’re like, “This is what I will get to do when I grow up.” To 12-year-old me, however, this video opened a portal into a more unconventional and subversive way of being feminine. I loooved “Check on It” (had it as a ringtone on my first ever phone), but “Green Light” was different—latex and leather; fetish heels; Beyoncé with dark hair, crawling between the dancers’ legs! I personally believe that the next time Beyoncé went into a comparatively sensual, dark, twisted form of femininity as this was on “Haunted” in 2013.

Since then, I’ve learned that the music video was inspired by Robert Palmer’s “Addicted to Love,” a song I’ve adored since discovering it through a Florence + the Machine cover. Certain visual moments rang a little bell in my tween subconscious—Shakira covered in oil in “La Tortura,” J.Lo dancing in “I’m Glad,” Britney and Madonna almost kissing in “Me Against the Music”—in retrospect it’s like, “Duh, you like girls, Miss Thing!”

Chris Panella — Breaking News Journalist for Insider

Lady Gaga’s fetish-filled, Cabaret-esque music video for “Alejandro” was particularly impactful a variety of ways—I grew up Catholic and incredibly queer, so you do the math—but there’s one sequence I couldn’t keep out of my horny teenage gay brain. About halfway through the video, Gaga and a group of scantily-clad, heel-wearing male dancers perform on stripped-down beds, executing various sex positions and BDSM-inspired techniques with whips. When “Alejandro” came out, I had never seen something *quite* like that, and the kinky, homoerotic aesthetics completely captured me. I was also stunned by how Gaga played with roles and power dynamics in the bedroom, as well as the androgyny of both her and her male dancers’ gender expressions. It unlocked many aspects of my identity—it was also fucking iconic and hot.

Brian Burns — Writer & Museum Educator

Like Bernadette in 1850s Lourdes, with all the mysticism and pomp that implies, a Marian apparition all my own, Madonna appeared to me one day in 1998 suburban New Jersey. I was four years old, and me and my sisters were watching some programmed block of classic music videos, any one of which came out, imaginably, years before we were born. That said, there’s only one video that I remember from that day. Because it was during said video when it happened. When she visited me. Madonna, in the Mary Lambert-directed music video for—what else?—“Like a Virgin.” But it wasn’t so much the video that I remember as this one specific moment, a particular shot that harbored a beauty or a power mighty enough to stay with me all this time. It’s during the second chorus, just shy of the two minute mark, 1:54 to be specific, when Madonna sets her hand on a glass-paned door and walks through it, refracted, heavenly, within its diamond-shaped frames. I never forgot it. I never could. Now, whatever it was about this image of Madonna walking through a door that managed to alter the very pathways of my mind, setting me up for a lifetime of loving Madonna not all that differently from how I love my own mother—who knows. But thank God for it. Because it’s no coincidence that Madonna’s singing “touched for the very first time” as she passes through that doorway—it’s a blessing.

Valerie Keaton — Writer

The screen-based music moment that shifted something in my brain the most was the dance scene set to “Kool Thing” by Sonic Youth in Hal Hartley’s 1992 film Simple Men. I saw this clip on YouTube long before I watched the rest of the movie, or had any greater understanding of who Hal Hartley was. That did not matter, because immediately upon first watching this video I was entranced by Elina Löwensohn as a screen presence.

At 16 or 17 when I first saw this, I was already pretty sure that I was a girl, but I wouldn’t come out for a few more years for an array of reasons. During this limbo period, one thing I would ponder on a lot was “Who will I be?” because while closeted I was deeply shy and did not know how I wanted to express myself once I got out of my shell.

What this clip gave me was an inspiration for who I wanted to become. And the external parallels between myself and Elina are obvious; I have very similar blunt bangs to hers, I own many striped tops, and I love wearing skirts. But what inspires me most goes beyond that, it’s the fact that she dances alone in the bar for herself, not caring of how anyone else would react. That is why this moment shifted my brain.

Yomira

I can trace back the origin of my adoration for Beyoncé to July 12, 2006—the day that I saw “Déjà Vu” premiere on TRL. I was familiar with her work and liked it, but this was different. The iconic dance scene in the sand (and the editing!), it just awoke something in me. The ferocity and freeness of her dancing, I still find it so intoxicating and euphoric to this day. I feel forever indebted to TRL for all the great moments like this that it gave me. This video served as the gateway for my obsession with music, pop culture, and music videos. It led me down the rabbit hole of the incredible women who came before her and influenced her. It made me want to find more videos that could make me feel as exhilarated as this woman had just made me feel. Before this video, I really didn’t think much about how music and music videos were made, but I became a woman possessed. I wanted to know everything about the entire process, and thankfully with Beyoncé, there is always so much to be learned about her craft.

Ian Olympio, Television Writer & Producer

At seven years old, my world was stopped and fundamentally reordered by the “…Baby One More Time” video. It was the heyday of the WB network, and I was deeply obsessed with the concept of the American teen. Britney Jean Spears, dancing through high school halls in a midriff-baring Catholic school uniform, embodied the energy of life at the edge of a century. She was familiar but dangerously contemporary, promising the future. She was the apex of a uniquely American ideal: the teenage dream

I had no idea who Britney was, but I knew instantaneously that I’d love her forever. She was the first pop star who could belong to me—not like Michael, Janet, or Madonna, whose careers began before I was born. She was creating herself and I was drawn to the power in that. Funny how queer boys are genetically coded to see themselves in pop divas.

Britney materialized out of nowhere and announced her arrival thunderously. The song was massive, but so was the video. They’d be eternally inextricable. That was Britney’s magic—she understood the power of an image. After three minutes and 57 seconds, I bought into the lore of Britney: the down-to-Earth beauty next door in search of love. I wanted to know all her secrets and to drown in her beauty. But most importantly, I hoped my undying devotion could ease the pain of the loneliness she sang about, which shone in her big brown eyes. Did we all have that same wish?

Andrew Kendall — Alleged Lecturer and Presumed Writer

I always say that my affinity for musical cinema is predicated on what my mother now calls my “Bollywood phase,” which ran from 1998 to 2002. But then, what could I do when my first in-cinema experience was the Guyanese premiere of Mani Ratnam’s Dil Se.., courtesy of my mother. The opening number in that film (from A.R. Rahman’s gorgeous score) is “Chaiyya Chaiyya,” which features Shahrukh Khan, Malaika Arora, and a slew of dancers gyrating atop a moving train winding its way through the picturesque Ooty valley. I could write for days on the musicality and lyricism of the number, some of Rahman’s strongest work, which makes his Oscar win for Slumdog Millionaire feels so strange in such a wonderful career, but the visuals… oh the visuals…

This is not movie-magic imitating a train ride, but a group of talented dancers and musicians dancing atop a moving train with a seductive energy without the use of a harness. Certainly, this is not nominally queer, and yet I always think of my Bollywood adoration as part of my own journey with queerness. For so many, whether our queer awakening came early or late in life, there is an inherent level of daring exuberance that comes with the willingness to be openly queer, and even if Bollywood cinema has had its own complications with representing queerness, I can trace my love of excess, spectacle, dance, earnestness, lyrical sumptuousness, and aesthetic clarity to Bollywood, and specifically to Dil Se.. (so beautiful and tragic).

Oh God, do I remember that moment where the train goes through the tunnel and shadows fall on the wall and the voices of Sukhwinder Singh and Sapna Awasthi sing while the dancers appear onscreen. I feel joy, I feel possibility, and I feel a weird pang in my heart. Each character in Dil Se.. lives and dies by their ideals, and oh how important that is for the future of queerness. For the very root of queerness is found in making the things that exist work for us. I don’t know why my mother thought that was an ideal first-cinema watch, but I know that whenever I hear that song, I feel tempted to text her to say it’s playing. And the literary adult that I have become cannot help drawing parallels between the naturalistic liveliness as a metaphor for the open plains being daring and assertive, and the daringness to be loud and proud and queer.

And how evocative when I turn to the English translation of the lyrics and find a line as wonderful as, “The royal flower stands upright with pride. Only its fragrance gives its place away.” Of course, I think of “Chaiyya Chaiyya”—let us bloom with pride, unharnessed as we dance atop a train.

Coleman Spilde — Entertainment Critic

The uncut, 4K edition of the advertisement for Lady Gaga’s first fragrance, Fame, rattled my brain long after I already had accepted that Gaga was my pop music lord and savior. “Bad Romance” changed my life, but the Fame ad spoke to a much deeper, darker side of Gaga that even she seemed afraid to fully tap into. The trippy visual is violent and macabre, with an eerie undercurrent of powerful loathsomeness simmering just out of sight. To quote every annoying person on Twitter, it genuinely is Lynchian, in the best ways. It reminds me of the CGI effects in Twin Peaks: The Return, which felt far less like they were generated by some computer but rather always existing, in another realm that’s beyond our reach until dark forces align. Its written preface, “Luxury propels vanity into dangerous places,” is the perfect, Gaga-ian way of being just vague enough about her art to let fans and critics extract what they want from the film, without missing the message. Her toying with the concepts of fame and opulence—and how those things inevitably lead to corruption, no matter what—is so fascinating to me. Watching it now feels like her accepting there is no way out of the sumptuous prison she’s crafted for herself. Might as well drink from the well, and let its offerings seep into her bloodstream to speed up the transmogrification; bearing witness to the gradual change would be too horrific, darling.

Ursula Muñoz S. — Writer, Critic

My queer awakening came in the sixth grade, in the form of the 2010 FIFA Opening Ceremony where Shakira performed her now platinum-certified cup song, “Waka Waka (This Time For Africa),” along with previous hits “She Wolf” and “Hips Don’t Lie.” Coming from a Hispanic background, I had obviously heard Shakira’s music before then, but only had a vague recollection of what she looked like. I distinctly remember my chest pounding out of nowhere as I watched her writhe onstage in her cut-out leotard with her abs on full display—moving the way I’d never seen anyone move before. I began to sweat nervously, and with this came a strange feeling in the pit of my stomach which forced me to stop watching.

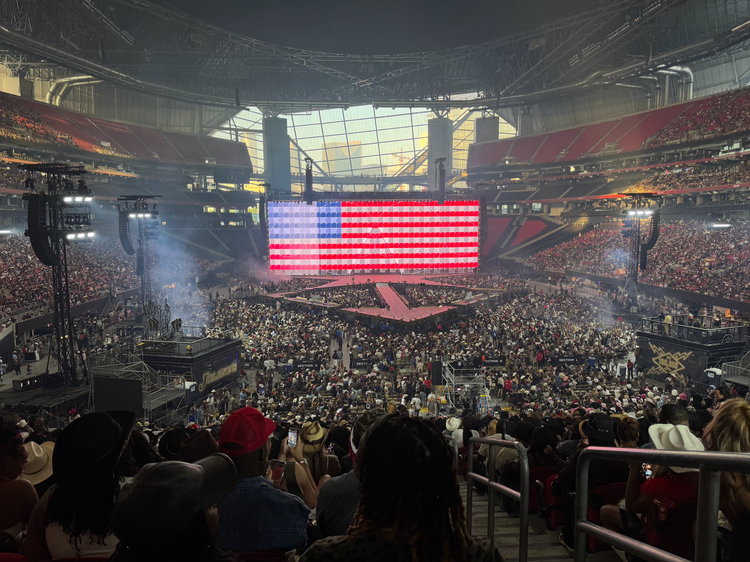

I didn’t admit to myself that I liked girls—let alone come out to anyone—for a long time after that. For many of us, growing up queer meant hearing kids use our labels as insults and watching adults treat homosexuality as a controversial topic not unlike politics and religion. Although my own parents have always been accepting, the social climate we lived in was enough to make me suppress my sexuality for years. Looking back, however, I almost feel indebted to Shakira and her ridiculous abs for helping me discover this part of myself sooner rather than later. And for what it’s worth, I’m sure her and J.Lo’s 2020 Super Bowl Halftime Show did for younger queers what 2010’s FIFA Opening Ceremony did for me.

Mononym Mythology is a music video culture newsletter by me, Sydney Urbanek, where I write about mostly pop stars and their visual antics. Here’s where you can say hello (if you received this in your inbox, you can also reply directly to this email), here’s where you can subscribe, and I’m also on Twitter and Instagram.