From Belinda to Britney

Given that I’m forced to write this with a surprise Weimaraner puppy snoring in my lap (more on that some other time), I’ll keep this short and sweet.

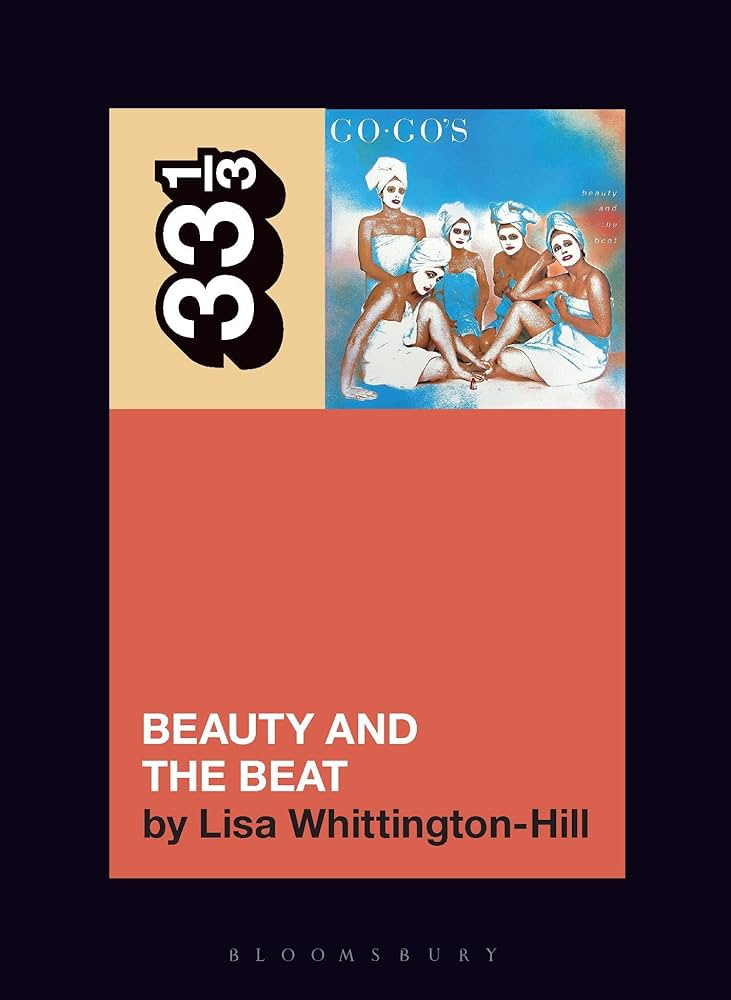

My friend Lisa Whittington-Hill is a fellow writer here in Toronto and also the publisher of This, a magazine I’ve been fortunate to work with a couple times now in the context of noted memoirist Britney Jean Spears. Lisa has Zoomed with me twice this year out of the goodness of her heart—the first time to talk about a book proposal I’ll see to completion if I can ever get the aforementioned puppy out of my lap, but more recently and importantly to chat about her own work as an author. She’s done something decidedly unhinged this fall, which is publish two different books more or less in tandem: the 33 1/3 on Beauty and the Beat (1981) by the Go-Go’s—an album we both love for different but overlapping reasons, not to mention an early-MTV staple—and the essay collection Girls, Interrupted: How Pop Culture Is Failing Women.

Below is a lightly edited version of the latter conversation, mostly about Beauty and the Beat but where it was impossible not to also get into the book’s so-called ‘sister project.’ You’ll see why!

My day has so far been spent re-listening to the album and watching back a bunch of Go-Go’s videos, so I’ll thank you for that.

They are so great… they are so great.

It’s interesting because I guess I count as a young millennial, or even a zillennial, and something I was thinking about while reading this book was how the Go-Go’s were kind of… I don’t want to say “made relevant again,” but I guess it is sort of what I mean… by these different millennial touchpoints that used their hits when I was a kid. So 13 Going on 30 (2004) was a big one with “Head Over Heels” in the opening credits...

...and then Hilary and Haylie Duff covered “Our Lips and Sealed,” and if you ever saw that post-American Idol movie From Justin to Kelly (2003)…

I never saw it but I’m aware of it, for sure.

...Kelly Clarkson covered “Vacation” in the opening credits of that movie.

I’m gonna check that out.

I can’t in good faith say that it’s a great movie, but it’s a lot of fun, and the music is good. But yeah, there was this big wave of Go-Go’s music hitting young girls when I was a young girl. I don’t necessarily know what that would have been, if there was a sort of 20-year something. But, all of which to say: I feel like I grew up with their music even though the first time I heard it, it wasn’t always through Belinda Carlisle’s voice. I also watched Fast Times at Ridgemont High (1982) pretty young, potentially too young. So I did encounter the band at a similar age as I think you did. Tell me a little about encountering the Go-Go’s proper for the first time.

I always forget that they use a song at the beginning of Fast Times.

Beauty and the Beat came out in July of 1981, so that was the summer before my tenth birthday, and I really didn’t discover it until it had been out for six months to a year. One of my closest friends had an older sister who was a teenager and had the album and loved the Go-Go’s, and we kind of discovered it that way. And for me, it just blew my whole world open, this idea that there were these five women and they wrote their own songs and played their own instruments.

MTV launched a month after Beauty and the Beat came out, so the Go-Go’s were a big part of MTV in its early days. But on the radio, and even on MTV, we saw a lot of male musicians and bands, and to see five women—punk-looking, fearless—we just kind of… What the hell is this and how can we… we want to do this! And I remember it totally changed my world. It opened up a world of possibilities.

At the time, there was nothing like the Go-Go’s. I remember in school, we did a Battle of the Bands. And my friends and I… there were never any really cool female musicians or bands that we could choose. The boys always had tons of options—there were always two or three Van Halens; they had all the choices but they always chose Van Halen. And we finally had an option! So we did the Go-Go’s. There was finally a band.

Listening to Beauty and the Beat, I remember saving up my allowance money to go and buy it at the mall; it was one of the first records I bought. And seeing them in videos—the whole idea of seeing musicians in videos on your TV, not just on an album cover, was amazing. But really, they changed my world. I was like, This is possible.

And when you say “This is possible,” were you a kid who wanted to make music, or do you mean more of a general “As a young girl, I can do x or y”?

I think both. I’d always taken piano lessons or played the organ. I had to play the recorder in school, which was awful. [Both of us laughing because same.] But I’d never thought about actually playing an instrument, or singing. The Go-Go’s made that seem possible. It made me want to play the drums. It made me want to be Jane Wiedlin playing an instrument, or Gina Schock… but I think they were these women who really opened up all these possibilities beyond music.

I’m curious about your music taste growing up and how the Go-Go’s fit into it. I assume you were probably listening to lots of people, but I know from past conversations we’ve had that you’re also an admirer of Courtney Love. And it seems like the book is partly you weaving all of these threads together, like Here are all the things I care about and here’s how they fit into this history.

I think that’s really interesting… the Go-Go’s were a game-changing band for me in terms of showing me possibilities as a young girl, all the things I could do.

But I think when I started to research the book and put it together, that was the thing I wanted to talk about. I really believe, and I make this argument in the book, the Go-Go’s were kind of the original riot grrrls. I was reading all these things where people like Kathleen Hanna and Courtney Love would talk about the influence the Go-Go’s had on them.

I remember writing one night, and I was watching this performance clip of the Go-Go’s playing at an L.A. punk club. And watching the video, you could see them being right there on a bill with, like, Bikini Kill. And I think, for me, it was interesting to talk about the Go-Go’s and talk about them influencing riot grrrl musicians and talk about them influencing Courtney Love—and talk about Britney Spears and Christina Aguilera and “pop princesses” and all that. All these pieces of things I liked, I started to put together.

The way that you were talking earlier about the Go-Go’s opening up this universe you didn’t know existed, the first acts to do that for me were Britney Spears and Shania Twain and Avril Lavigne. And it was fun, through that lens, to have Britney be one of your later threads that you weave in. There’s sort of a Trojan Horse component to the book, where it’s about Beauty and the Beat but it’s not entirely about Beauty and the Beat.

I worried about that a little bit when I was working on the proposal and when I was writing the book. People that are hardcore Go-Go’s fans and hardcore fans of the album—and everyone should be, it’s an amazing album!—might read the book and be like, Why is she talking about Britney Spears now? Why am I getting a history of riot grrrl? But I also like the surprising aspect of weaving all these things together, and I tried to include enough about Beauty and the Beat that it would appeal to those people, so they wouldn’t feel like, Hey, I spent my money on this book. Why am I reading about Christina Aguilera?

It does help hammer home the relevance for nowadays. And a lot of these conversations you have as they relate to the Go-Go’s are entirely back in the news, for sometimes sad reasons.

If I were describing this book to someone, I would probably say something like: one woman in the 2020s looks back at one all-women band’s experience in the early ‘80s and reflects on how much, but especially how little, has changed.

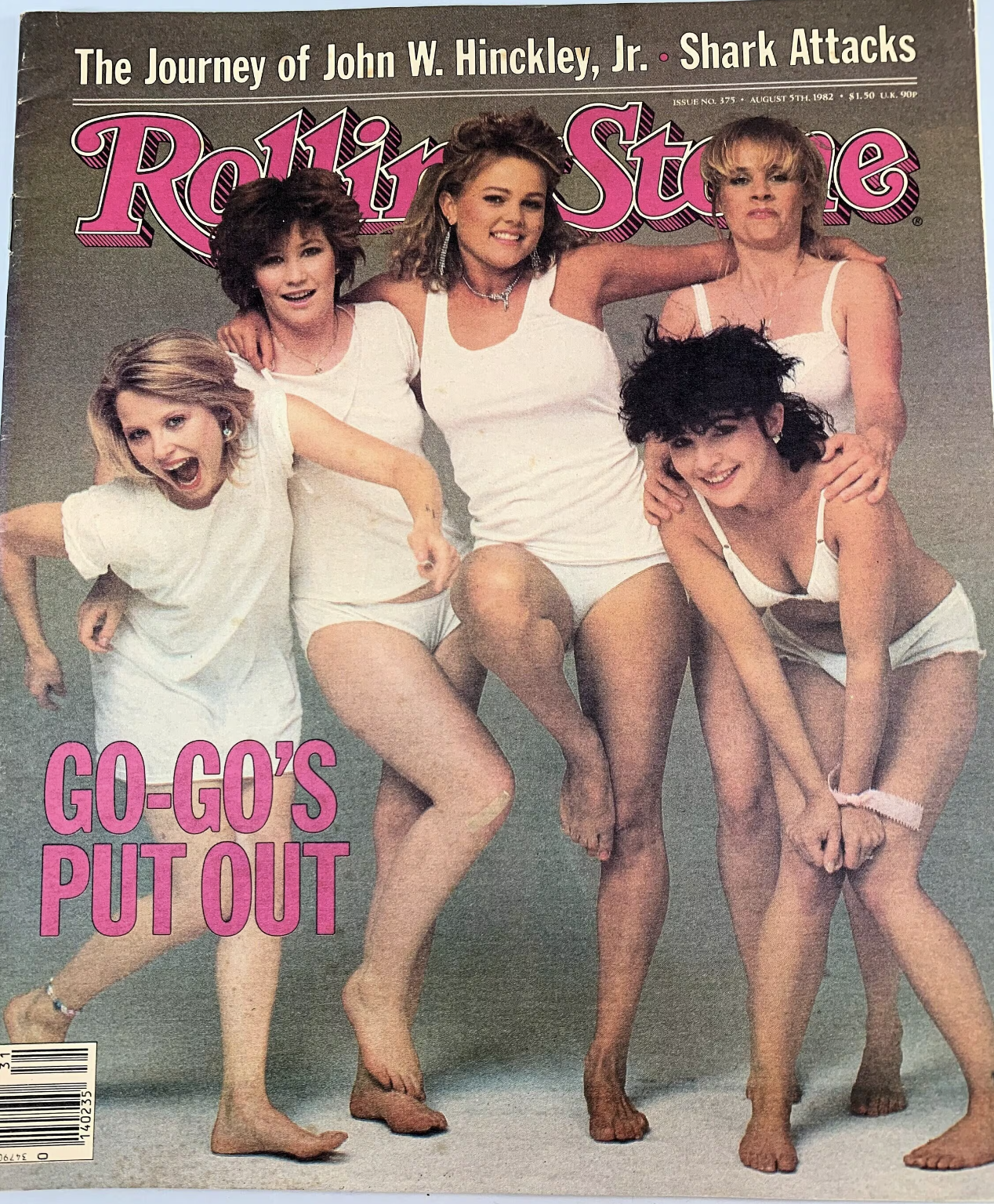

Yeah, one of the big messages of the book is looking at the misogyny and the sexism that the Go-Go’s experienced, and looking at how little has really changed for female musicians. There would be times where I’d be reading a Rolling Stone article or interview, a profile of the Go-Go’s from 1982, and then reading a Rolling Stone profile of, like, Taylor Swift decades later. The interview questions still the same—asking about boyfriends, asking about fashion.

So tell me about the road to this book, as in the actual writing of it. And you can also talk about your other one at the same time! I have a feeling that they’re kind of sister projects.

They are! I’d always wanted to write a 33 1/3 because I think the series is so amazing, and I love reading people’s takes on different albums, and what albums they choose, and what they choose to talk about. I wrote a proposal for one in 20…15 and it didn’t get selected—it was for a different album. And I thought, I’m gonna keep trying. And when the call for proposals came out in 2021, I really thought a lot about what band I wanted to do and what album I wanted to do, and I really wanted to do a female musician or an all-women band—that was important because I think they’re underrepresented in the series.

And I made a list, and the Go-Go’s were on it because, at the time, the documentary had come out and there was talk of them finally being inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. I felt like people were talking about the Go-Go’s again, and I think I kept coming back to them because of how influential they are for me. But one of the things people think about with this series is, we all have albums that we love or that resonate with us, or that we have a deep meaning with, but what’s the conversation we’re gonna have beyond that? No one wants to read a book that’s just me for 150 pages saying, “The Go-Go’s changed my life! The Go-Go’s changed my life!”

But the more I started to research, the more I was like, Wow, they endured all this sexism, all this misogyny. They couldn’t get a record deal because no one wanted to sign an all-girl band. And I started to think about that. I wanted to tell their story because I think their story had been forgotten, or hadn’t been told enough. When we talk about feminist bands, we don’t often talk about the Go-Go’s, and I think that’s a huge problem.

And the more I started to research and read interviews with them and immerse myself in the world of the Go-Go’s, which was a fun world to immerse myself in, the more I started to be like, Hey, so much of this hasn’t changed. And I’m really, really interested in gender bias in pop culture and looking at how pop culture treats women, how pop culture is failing women, and I was interested in zoning in on how the Go-Go’s were treated by the music industry and the media. And female musicians are still treated that way. It’s really depressing to think that the way we were talking about a girl group in 1981 hasn’t changed in 2023.

So in my case, the music itself was not new to me reading this book, but I knew virtually nothing about the band behind the music… which to some degree is a win of its own, kind of. But the big takeaway, then—the fact that the band was being sold as this very different entity from what they were behind the scenes, and what they originated as—that was mind-blowing as someone who had no idea.

And I think that’s one of the reasons I wanted to tell their story, too. Behind the Music specials are problematic and the Go-Go’s hate the one about them, but it’s interesting to watch. The Go-Go’s story is one of contradictions, in that they really were marketed as these wholesome, sweet, bubbly girls next door. Behind the scenes… I think Charlotte Caffey gave an interview with CBC and she called them “America’s sweethearts from Hell.”

Caffey had a heroin problem for many, many years. Belinda Carlisle had a $300-a-day cocaine habit. They were being marketed to preteens like me at the time as these girls, and then offstage they’re drinking, they’re doing drugs, they love to go out looking for a party and looking for fun. They came about in the L.A. punk scene, and that is forgotten from their story. And then this whole aspect that they were not this really cute, singing sorority.

I think we still have that. Male musicians are allowed to party as hard as they want, and that kind of stuff is glorified, but we don’t like it in our female musicians. We think it’s really cool when, like, Anthony Kiedis talks about how many drugs he did, or Ozzy Osbourne talks about that. We don’t want that from our female musicians; we want them to hide it away. It’s really interesting to hear the Go-Go’s talk about what they were doing offstage, and then the image they had to present onstage and in the press.

The contradictions point is really interesting to me because it seems like women in the public eye aren’t allowed to have different facets of themselves. It’s kind of like, Check a box: are you a) the girl next door, or b) a superskank—you can’t be both! And anytime you see someone try to move from one box to the next, or inhabit two at once, you run into these roadblocks with the media landscape. And it doesn’t seem like they exist in quite the same way for men in rock, men in pop.

I think there’s a quote where Kathy Valentine talks about how they had to check a box, exactly—they had to decide. And their box was “wholesome girls next door,” “America’s sweethearts.” And I think you’re right: you have to be the good girl or the bad girl. There’s only one box that exists. When female musicians try to move out of the box that they’ve been put into, that’s where you get “Oooh, reinvention!” and all this other stuff. That’s another topic.

I don’t mean to ask a leading question, but I’m curious if this issue is a personal one, if something makes you care about it in particular. I was thinking about it a lot while reading, how you can be a bunch of different things, but if someone is still not letting you be a bunch of different things, that’s going to be a problem. There’s only so much you can do and then there’s the other half of the equation: am I allowed to be a sleepover-friendly artist who’s also got a $300-a-day cocaine habit?

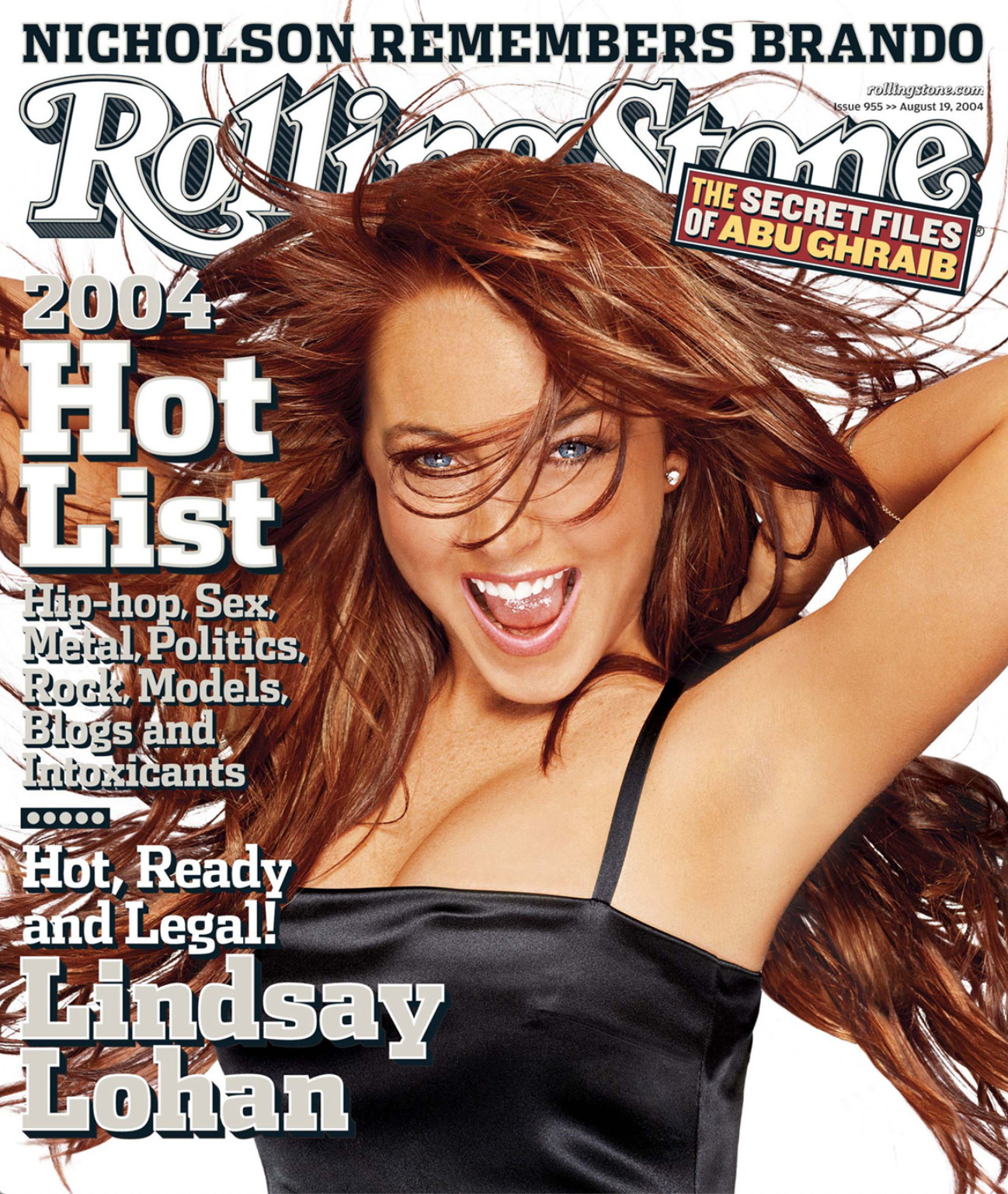

One of the things I keep coming back to in the book… I can’t imagine the sort of pressure on the Go-Go’s, and one of the things Belinda Carlisle talks about is that it’s a good thing they came up at the time they did, when there wasn’t social media and the internet and cellphones. She says that they would have been “the Lindsay Lohans of our time” if all that technology had existed.

I have to wonder what it was doing to them individually as people. Having to go out and smile and have this preteen fanbase, and be billed as these sleepover buddies for preteen girls. Like, are you going to bring your box of cocaine to the sleepover?

[Snort-laughing] Right.

Jane Wiedlin always talks about it in interviews as “robo Go-Go-ing,” like you would plaster this smile on your face and go out and do it. It wasn’t just the partying and the drugs; there was also a lot of in-fighting, like they were always billed as these girls that all got along and loved each other and were sisters. There was a point where they were suing each other, and they didn’t talk, and they behaved in all these ways that weren’t very ladylike.

But at the same time, sort of like normal adult women.

Like normal adult women.

It’s interesting, the quote you brought up about being the Lindsay Lohans of their time, it was kind of a blessing and a curse that the media landscape was the way it was.

There are a few points in the book where you talk about Fanny—another all-women band, super talented, but where the world wasn’t really ready for them. I had never heard of Fanny until a couple years ago because there was that documentary, and I reviewed it and learned their entire story in one sitting. Their story preceded the Go-Go’s story by about a decade, with a similar kind of rise-and-fall timeline to each band, a lot of similarities to the two stories.

And in sort of a sad way, where the needle has only moved so much by the time the Go-Go’s show up. There’s only so much an artist or a band can do themselves, there’s only so much talent they can bring to the table, but at a certain point the rest comes down to culture, it comes down to infrastructure. There’s this other piece of the puzzle that has nothing to do with you.

I wanted to talk a bit about the girl groups that came before the Go-Go’s. I wanted to talk about Fanny, and I wanted to talk about the Runaways because people assumed the Go-Go’s were like the Runaways in that they had been created by a man, had a Kim Fowley-like person behind them, a Svengali pulling the strings. I wanted to talk about the Slits because I thought it was important to talk about post-punk bands in England. But Fanny, I was so happy to see that documentary because I think a lot of people don’t… I didn’t know much about Fanny, and I learned a lot. Everyone should watch it.

I re-read my review because I wanted to remind myself what I’d said, and I did something that I think you could criticize, which is: they often get talked about in the context of David Bowie [who dated a member and hyped the group up on one memorable occasion], and I did that. I don’t remember if I necessarily wrote the headline, but I probably did.

There’s a moment in the book where you describe that popular notion, “If they’re good and they’re girls, there must be a man behind it.” The problem is that sometimes there has been a Kim Fowley-like figure, and it drowns out these examples like the Go-Go’s where there isn’t one.

I’m trying to remember what the phrase you used was… “One-in, one-out?”

One-in, one-out. There could only be one female musician or band at a time. And I think I started to think about that a lot when I was working on the book because I think that policy means we don’t start to connect all of these things, in a way I tried to do.

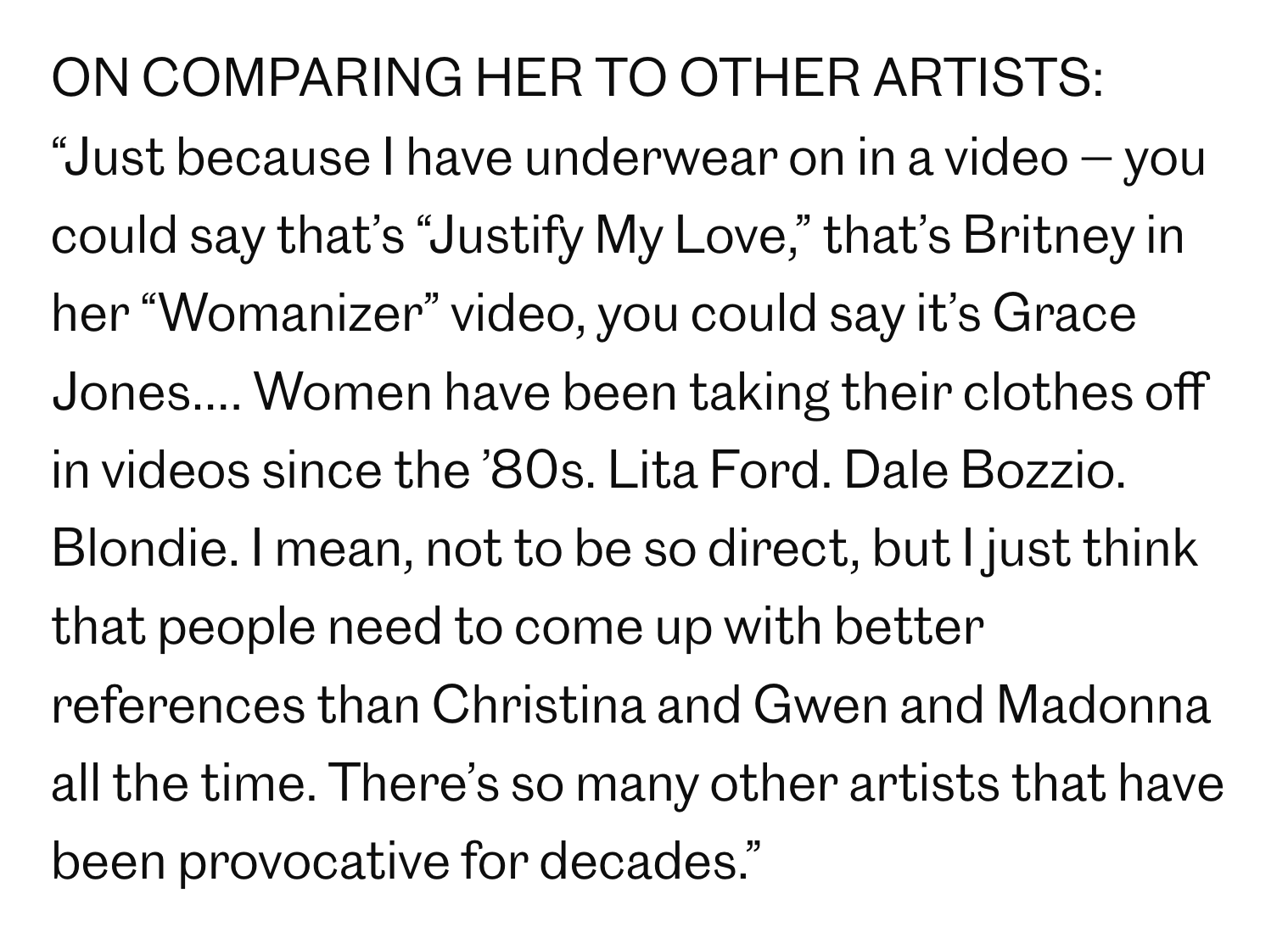

Maybe it’s just where I’m looking for it the most, but I see it so much in relation to both Madonna and Beyoncé. Recently I’ve been doing a lot of looking back at circa-2008 Lady Gaga stuff, and she’s being packaged in every magazine headline as “Madonna meets Gwen Stefani meets Britney Spears,” or “the new Madonna.” And meanwhile, Madonna that year embarked on what was until recently the highest-grossing tour by a woman ever. She hadn’t retired, she very emphatically hadn’t gone anywhere, but there’s this implication that’s like, Wrap it up! There’s a new you!

And there’s this parallel idea where, culturally, we’re so bad at letting famous women—or groups of them—exist in and of themselves, like they have to be the product of some soup of other famous women.

And it’s also the limited reference points people have when they talk about female musicians. Lady Gaga can’t just be her own thing. The media loves to do that, they love to start fake feuds.

I should grab it, but there’s this great quote from Gaga—who had her own references at the time, that weren’t necessarily the three I mentioned and only those three—but where she says something to the effect of, I think we could have more interesting conversations about my work if people had better reference points:

No one ever says it but I’m sure a lot of these artists are thinking it.

You also talk in the book about how the Bangles became this sort of set-up, manufactured feud for the Go-Go’s.

Yeah, I say this repeatedly in the book but the Go-Go’s were the first—and, to date, only—all-female band to write their own music, play their own instruments, and have a number-one album. The Bangles came close, but when the Bangles came after the Go-Go’s, people were writing about the Bangles like “the new Go-Go’s” or “now that the Go-Go’s are done, the Bangles can exist.”

Right.

They weren’t able to talk about the Bangles as [having] their own kind of identity. And I remember someone asking, like, “Oh, you wrote a 33 1/3 book about Beauty and the Beat. Are you sure the Go-Go’s are the first—and, to date, only—all-female band to have a number-one album, that wrote their own music, and played their own instruments?” I’m like, “Trust me, yes. I fact-checked it a million times.” “Well, what about the Bangles?” And they started to talk about, “I think the Bangles were only successful because the Go-Go’s were done.” And I’m like, Oh my God! More than one successful female band can exist at a time! Even in the ‘80s.

And I guess it’s complicated because the whole one-in, one-out thing is made easier by the fact that… it’s not like there are thousands of examples and reference points to pull from. At the end of the day, there are these chapters, where the Supremes and the Shangri-Las give way to the Runaways, and unfortunately that list is not any longer than it actually is.

But so, respectfully, what possesses someone to write and promote two books at once?

I don’t know.

What is wrong with you?

I guess it just sort of happened, timing-wise, that everything coincided. And I was like, Okay! I’ll try to do them at once. But they are similar. And it was kind of depressing because I spent the last two years looking at how pop culture is failing women, whether it was the Go-Go’s in the 33 1/3 or Britney Spears in the Girls, Interrupted book. But I think it’s something that’s super important to talk about, because looking at it over the last two years, the same patterns keep repeating. So I guess I just decided: I have these two opportunities, and I’m very blessed to have these two opportunities, and I’m just gonna do it and see what happens.

Did you write them at once, or did you submit one and then write the other?

So the 33 1/3 proposal… I think the deadline was in May 2021, so I was still in lockdown in my apartment, and I thought, This is the perfect time to write a 33 1/3. I’m just gonna try. I’ve tried before and it didn’t work, but I’ll try again and maybe this will be my last try. And I felt good about the proposal, but you never know… I’m a cynic.

And then Girls, Interrupted is a collection of essays. Some of them are previously written and published pieces, which made it a bit easier to write, and some of them were things… there’s an essay in there on Courtney Love, which is a piece I’d written for Longreads a couple of years ago, there’s a piece in there I wrote for The Walrus, a piece for Catapult.

It did help that the subject matter overlapped. It was depressing, but it was also very, very interesting to get to spend two years with women in pop culture, and reading about the Go-Go’s and reading about Britney Spears and going back and reading old Us Weekly issues with Lindsay Lohan on the cover from the early- to mid-2000s.

The 33 1/3 got accepted, and I sort of finished that first and then worked on the other one. But I was thinking about them at the same time. I kind of felt like people would be like, “Ugh, all you ever talk about is how pop culture is crappy to women,” so I think people are glad that I’m gonna talk about some new stuff when we go out for wine.

Now that it’s been exorcised.

Here’s me talking again about Perez Hilton and how awful he was to Mischa Barton, you know.

So you said that you’re a cynic, but then you got lucky with these books. In the 21st century, in the 2020s music landscape, are there people you see as spiritual successors to the Go-Go’s these days? Are there artists right now giving you hope? Issues we used to botch culturally that now we’re getting better at? I’ll throw all that at you and see what comes back.

I spend a lot of time in the ‘90s, but I think one of the things I kept coming back to when I was writing, especially with the essay collection, was that… I often think social media can be a super toxic place and a dumpster fire and all that stuff, but I was thinking in the context of the Danny Masterson sentencing and the Mila Kunis/Ashton Kutcher apology video, and how awful that video was. But then I loved seeing people pulling up these clips of Ashton Kutcher from Punk’d, where he was talking inappropriately about Hilary Duff and the Olsen twins turning 18. And then people talking about Wilmer Valderrama and his problematic relationships with young stars… Lindsay Lohan… Mandy Moore…

Demi Lovato…

…Jennifer Love-Hewitt. But seeing people pulling up old Rolling Stone covers with Lindsay Lohan where she’d just turned 18, with the coverline “Hot, Ready, and Legal!”

One of the things I talk about in the collection is how social media has been really great in revisiting all of these things. Pulling up all these things like David Letterman interviewing Lindsay Lohan, and talking about how awful all the questions were, and how uncomfortable she looked. And revisiting and seeing how problematic all of it was. I’m inspired by that. I loved seeing Ashton Kutcher being dragged on Twitter. I have waited for the day.

That Wilmer Valderrama list is longer than I’d realized. I’m jumping around here obviously but that answer had me thinking about feminist awakenings… am I wrong in assuming that yours dovetailed with riot grrrl and stuff around that time?

I’m Gen X and for sure riot grrrl. I’ve also turned defending Courtney Love into an art form. I have been [defending her] basically since the mid-‘90s. I used to not get invited to parties because people didn’t want me to come and argue with men about Courtney Love. There was a time in the ‘90s where I had a no-Courtney clause: Lisa can come to the party, but…

Men love to argue about Courtney Love, and how she was responsible for Kurt Cobain’s addiction issues and his death, and how awful she is, and how he wrote all of Live Through This (1994). There was a lot of material for me to argue about. Maybe I wasn’t the most fun at parties, but yeah.

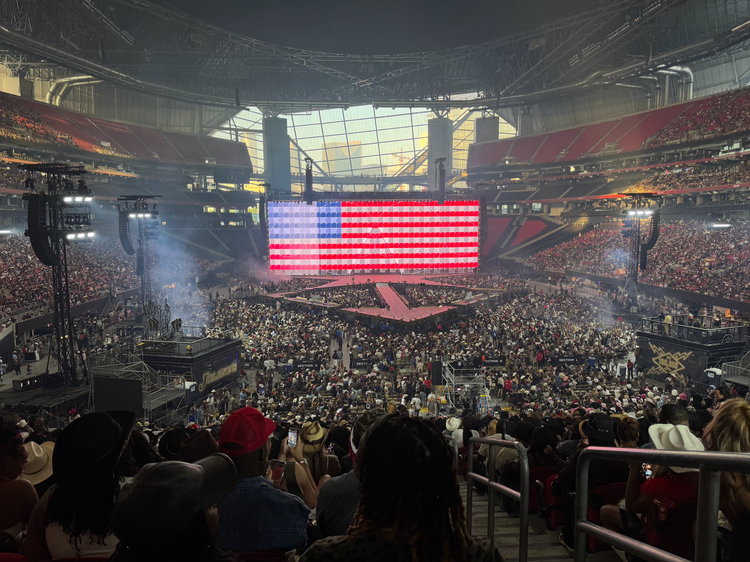

I’m really fascinated by this idea that MTV supposedly changed the gender makeup of live audiences. You quote Pat Benatar saying that she noticed more women showing up at her shows around 1982, i.e. months after she became the first woman to have a video play on MTV. That’s such an interesting, mind-blowing thing to think about.

And I wanted to include Pat Benatar because I’m always telling people this, and I think people are surprised by this: the second video to play on MTV after “Video Killed the Radio Star” (1979) was “You Better Run” (1980). And I remember when MTV launched because we didn’t have it in Canada at first. So I remember going to California and it was the coolest thing. I just locked myself in this room, and my mom would come and bring me food but I just sat there and watched MTV.

But yeah, Pat Benatar talks about how there were more women going to her concerts, and I think more women buying records after MTV launched... seeing Madonna or seeing Pat Benatar and going to the record store and seeking out these records. I know for me it was huge in terms of watching MTV or Friday Night Videos, and seeing all these women—being able to see them on something other than an album cover or in the pages of a magazine, which is all we had back then. I sound so old when I say that, but how MTV helped with the visibility of female artists. You started to see them, and you’d go buy the records and go to their concerts. The Go-Go’s talk about how they didn’t really want to make videos, but one reason they did want to make videos was, for them, it was super important that people saw them playing instruments. Because people thought someone else was playing their instruments on the album.

But MTV was huge, and in the early ‘80s: Madonna, Cyndi Lauper, Donna Summer, Chaka Kahn, Tina Turner, the Go-Go’s, the Bangles, all these women. And it was really amazing to see.

I don’t want to just describe the concept of MTV, but I guess it’s really one thing to hear someone’s voice on the radio, and another entirely to be dazzled by them moving on your screen. And it’s also, of course, one of those double-edged swords, where it drives really interesting visual presentation and it can be so inspiring to some little girl at home, but it’s also forcing interesting visual presentation, and that can make it harder to keep the focus on the music.

I think it was Nancy Wilson of Heart who talks in the I Want My MTV (2019) doc about how suddenly there was new pressure, because Heart went from being this uber-talented rock band, to still being that but now having to rethink the way they were presenting themselves. And suddenly there’s all this new attention on their looks, and their weight—which also happens to Belinda Carlisle in your story. So it’s like this minefield.

Yeah, I just finished rereading I Want My MTV the book, and Heart talks about this pressure on your appearance. It used to be that you could just make your record and go on tour. But MTV added this whole other thing, where image became so important and how you looked became part of the package. And Belinda Carlisle was the one who got called chubby—people commented on her weight—and that was really hard.

It was also hard because as a preteen watching MTV, you would see women and you would see Madonna and Cyndi Lauper, and that was super empowering and amazing to see, but then you would also see the scantily clad girls in the Duran Duran videos, or the teacher dancing in the cage in the “Hot for Teacher” (1984) video, or Tawny Kitaen doing the splits on the hood of a car. It was a really weird time to watch videos.

And I guess there’s kind of a repeat of that weirdness in the early 2000s. You talk about pop princesses and the hypersexualization of artists like Britney Spears and Christina Aguilera, where you’re being sold this blanket “It’s never been a better time to be a woman” thing, but when you look back at it 20 years removed, it’s like... What the hell? It’s so weird. And it makes you wonder what we’ll be revisiting in 20 years with the same kind of 20/20 hindsight.

Yeah.

Anyone reading an author interview with me is expecting me to ask a process question, and I’m curious… we’ve talked in the past about the way you like to self-edit and fact check, but how did you write this book in terms of the actual how? You have a job, so did you get up early before that job?

I long to be one of those people who wakes up at 5 a.m. and writes for two hours and then starts their day. I tried to be one of those people but then realized that I was setting myself up for failure. I wish I could be very disciplined and very structured in that way, but I’m not. A lot of my writing was on weekends, or late into the night, or taking a few days off and being able to write here and there. I write best in long spurts; I’m a person who will sit down and write for eight hours, and that works best for me. I’m not one of those writers who’s like, I’m gonna write for an hour a day. I tried that at the beginning and then I would feel really guilty when I didn’t write for an hour a day.

And then you try to do that thing where you stack the makeup hours on top of each other.

I think if I do another pop culture essay collection, one of the things I really have to think about is process. I listen to people talk about the craft of writing, and I’m just like… I drank a bunch of coffee and lived in the same sweatpants and a dirty Sonic Youth shirt for a week, and ordered all my food takeout. I’m certainly privileged to be able to do that.

And I imagine you probably had to listen to the album a thousand times. Do you have a favourite track?

“We Got the Beat” is always a favourite. It’s a classic and one that my friends and I, in the days of having the record at the sleepover, we would take the needle and keep putting it there.

I listened to the album a whole bunch, I watched a whole bunch of videos, I also read a bunch of books about the L.A. punk scene. And in some ways, I think if I could go back I’d be like, Okay, maybe we don’t have to read every book on the L.A. punk scene. And for the essay collection: Maybe we don’t have to read every Us Weekly with Lindsay Lohan on the cover.

It’s hard, right? You have this stack of books and you’re like, “My golden quote could be in one of them!” It’s a self-torture thing.

And I think writing about the Go-Go’s, they’re a band that means so much to me that I really felt I had to do them justice. What if the great quote is in here and I miss it? Or: I should go back and fact-check the whole book. I didn’t want to do them a disservice that way. And people also have really strong opinions about the 33 1/3 series. But mostly I wanted to do the Go-Go’s right because their story hasn’t been told enough, hasn’t been told in the right ways.

Is this the sort of book where you would love for them to read it, or is that a terrifying concept?

It’s kind of terrifying. I didn’t interview any of the band members, I just used research. Which I think some people find a little bit odd, but that’s out of, like… interviewing my childhood idol Belinda Carlisle is terrifying to me. But Kathy Valentine did retweet my [pub day announcement]. If I could go back and tell my 11-year-old self, “One day you’ll write a book about the Go-Go’s and Kathy Valentine will retweet it,” I would have stopped worrying about the flexed-arm hang in gym class. I kind of screamed to myself. And then someone posted about it and a couple of them liked it on Instagram. The idea of them reading it is exciting but also terrifying. It’s their story, and it’s an honour to be able to tell it, but it’s the idea of treating it with care and telling it in a way they’re happy with.

Do you picture a particular person who this book is for? Are you hoping to catch a certain generation, or anything along those lines?

I think what I like about the book is, if you like the Go-Go’s then hopefully you’ll like it; if you’re studying riot grrrl, you’ll like it. I do worry about hardcore Go-Go’s fans not being as interested in the chapters about riot grrrls or Britney Spears, but I’m also hoping that people see the connecting-dots aspect of it.

And I will say, one thing that really comes through reading it is how much research you did. It reads like you’ve read all the books you could have read. And for the record, I think “Automatic” might be my favourite song on the album.

That’s a great song, too! ●

Mononym Mythology is a music video culture newsletter by me, Sydney Urbanek, where I write about mostly pop stars and their visual antics. I do that for free—and actually pay to use this platform—so if you happened to get something out of this instalment, you’re more than welcome to buy me a coffee. The best way to support my work otherwise is by sharing it. Here’s where you can say hello (if you received this in your inbox, you can also reply directly to it), here’s where you can subscribe, and I’m also on Twitter and Instagram.