Following Bodies Through Space

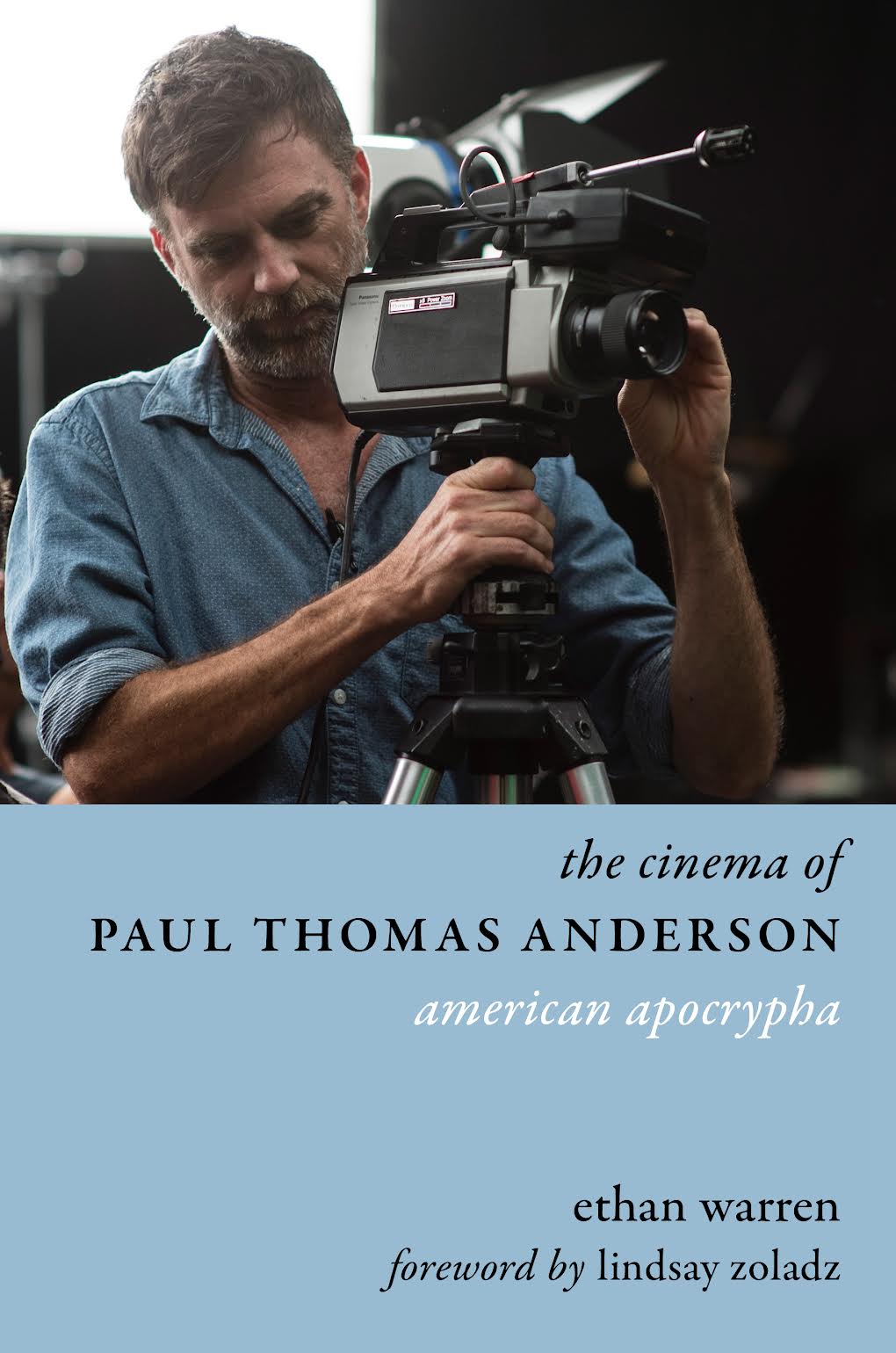

The only thing more fun than having a friend write a book is having that book turn out to be excellent. I’ve known that I wanted to interview my buddy Ethan Warren about his new (and first!) book, The Cinema of Paul Thomas Anderson: American Apocrypha, ever since a late-stage manuscript appeared in my email sometime last year for copy editing. But while that’s indeed my obligatory disclaimer, my involvement has zero to do with Ethan being here.

His book pays excellent attention to Anderson’s music video and music film career, which doesn’t exist as well as his narrative feature one so much as bolster it in fascinating ways. From Joanna Newsom to Radiohead, his music-world collaborators tend to already exist somewhere in the world of his features (with the notable exception of HAIM, who’ve now officially been brought into it via Licorice Pizza [2021]). And sure, I may also have wanted a reason to spend a week straight looking at Fiona Apple. So sue me!

Below is my chat with Ethan, which has been lightly edited for length and clarity. Among other things, we get into PTA’s personal and artistic relationship with the late, great Jonathan Demme, what it’s like to write a book with diehard fans in the back of your mind, and the trials and tribulations of making the plots of for-adults movies intelligible to three (very cute) small kids.

So I hear you wrote a book.

It’s true. You’re one of the first people who read that book, which I still greatly appreciate. But I did, I wrote a book. It’s surreal—that’s the dream, the lifelong dream, and I checked it off.

Was it fun?

No. It was scary the whole time. [Laughs]

Well, before we get into the actual book, can you tell me—putting said book aside however much you want—what Paul Thomas Anderson actually means to you? Which is a big question, I know. But what is your first PTA encounter, and what’s the one that actually does you in, since those are not always the same thing.

Well, my first encounter with him was seeing Punch-Drunk Love (2002) when I was like 16, and that is a movie I found violently alienating, and I immediately felt like I had an enemy for life in this guy who had caused such horrible feelings in me. [Laughs] Because it’s a movie that is very aggressive and abrasive. And beautiful and romantic and ecstatic, but also just very… it cuts against the grain of what a 16-year-old in the year 2002 was expecting.

And then it took until his next movie, There Will Be Blood (2007), for one of them to click for me. I went and saw that one just because it was there; I wasn’t expecting anything of it because I’d hated this guy’s last movie. And I fell in love with it within the first couple of seconds, I want to say. It just announces itself as something so compelling and unusual. And from there, I was really in the tank for him, but I still could never get my head around Punch-Drunk Love—it took years and years for me to come back around to that one and appreciate it. As I became a greater and greater fan of the guy’s work, there was still that one hole in there where I just hated that one movie. And now I love it.

That’s so interesting. I guess Punch-Drunk Love was a big turning point for him as a filmmaker.

That’s right, it was the one where he broke down the way he’d worked before and kind of rebuilt it.

And so, how do we arrive at The Cinema of Paul Thomas Anderson: American Apocrypha? I’m curious in particular about the subtitle, and why that’s your big thread.

Well, it’s this idea that he has cast himself as a bit of a historian. He has not made a movie that takes place in the present day since Punch-Drunk Love, and his movies often take place in these moments of historical upheaval—the shadow of World War II, the death of the ‘60s, the first couple decades of the 20th century (eliding World War I but using signifiers of World War I). He sets his movies in these moments of great American upheaval, and as Adam Nayman did in his fantastic book [on PTA], you can line them all up and create this parallel history of the 20th century.

But what’s so interesting about that history, to me, is the way [PTA] plays incredibly fast and loose with the details that would mark a serious historian. He takes the past as an excuse to create these ecstatic visions of poetic grandiosity. And he was saying this all over the Licorice Pizza press tour, he leaves the details that are inconvenient to him in the dust. He sees himself as a vampire or a shark; he just moves through the truth using what he wants, and leaving the rest behind him.

Right, so I wanted to chat with you in part because he obviously has this robust music-related body of work, but also because there’s this really interesting idea in his work across the board, and in your book, of mythmaking—gathering all your pieces, weeding out the inconvenient ones, spinning certain other ones differently, and then delivering this final product, which is sort of exactly what this newsletter is about. And how different artists do that with history and autobiography. That blur between “This happened” and “This didn’t necessarily happen.” And sometimes the ethical fuzziness there, but more importantly what the actual effect is. Was this a proposal that you wrote initially?

It was. This first came about because, years and years ago, Little White Lies did their three books [“Close-Ups”] on Wes Anderson, vampire movies, and New York movies. And then they put out a call for proposals for a next couple of books in that series, and I put one together on Paul Thomas Anderson. And, as far as I know, no other books ever came out in that series, so I was sitting on this proposal for the next several years.

And then I got emailing with the acquiring editor at Wallflower Press, which is a shingle of Columbia University Press. I was emailing with Ryan Groendyk, and I was trying to pitch him for a different series, “Cultographies”—I wanted to write about Brian De Palma’s Phantom of the Paradise (1974) for them. It turned out they had shut that series down due to lack of interest, but I had my foot in the door, and they said, “If you want to submit a proposal for one of our other lines, go for it.” And I said, “Well I have all of this material for a Paul Thomas Anderson book, so what if I spiffed that up?” And that’s what I did.

You should still write that book one day, the Phantom of the Paradise one, just for the record. Because I was going to be speaking with you, I actually had my Phantom of the Opera sweater on, which I think I probably had on the last time we spoke. But I got cream cheese on it in the last 15 minutes.

Oh no.

So I switched. Anyway, that’s not important.

It’s very important.

Okay so, prior to prepping for this, I actually had not seen the vast majority of the music video stuff. I’d seen “Across the Universe” (1998), although I’d forgotten how great that video is, and I’d never before clocked the John C. Reilly cameo because I’d never really watched it that closely. And I’d seen Anima (2019) for visual album reasons. But virtually everything else was new to me; I think I only watched Valentine (2017) for the first time after reading your book last year. Just as an open-ended question, what role do you feel these shorter-form projects play in PTA’s body of work? How important are his music videos to understanding him as a filmmaker, as a person, what have you?

Well, he has developed as a director of music videos very much parallel to his development as a director of features; unlike a lot of directors who start in music videos and move into features, he didn’t direct his first video until after Boogie Nights (1997). And has only worked more prolifically in videos over time, as opposed to some directors who phase out that part of their career.

And you can see the way certain reflections of the feature that’s being made in parallel to the music video emerge. Like, he did a music video [1997’s “Try”] for Michael Penn, who composed or co-composed his first few movies, that’s using a lot of the visual language of Boogie Nights—these long, languid takes, and a lot of highly choreographed stuff going on around the margins. And then you get to something like “Hot Knife” (2013), the Fiona Apple music video that’s being shot around the same time as The Master (2012), which has really interesting photography that’s similar to the portrait photography you see Freddie Quell taking in The Master. So you see these parallels emerge.

I think what the videos are most significant for is the way they’ve let him develop his team and streamline his camera crew. At this point, he notoriously does not use a cinematographer; his camera crew just operates autonomously. And I don’t know how you get to that point without all of the honing they did on the HAIM music videos.

Right, so just duplicating a tiny bit of what you said—and I think this is one of the things that makes him really interesting to me—he doesn’t start directing videos as “feature practice” (in quotes), although I guess he did some PA’ing.

He did when he was sort of kicking around Hollywood.

He doesn’t start making them until after Hard Eight (1996), and then they never stop. It’s what he’s done for three decades now between the features, but sort of as extensions of them sometimes. Whether it’s I want to keep working with this one collaborator or I’m gonna bring this collaborator’s romantic or professional partner into my fold. That part’s really interesting. So he has this web of collaborators, and then he’s a serial monogamist with the music video clients, if that’s even the right word here.

Though I’ll say, he did stop for 13 years; he did not direct a video between 2000 and 2013.

And in your book, you connect that to the general weirdness the industry was experiencing in that moment, with the transition from MTV to the internet. And there are a lot of filmmakers in that boat; the music videos drop off sometime around the turn of the millennium, and then come back once they realize, Hey, we can do anything in the streaming era. And another interesting thing about PTA’s videos is that they’re often very long, where Joanna Newsom can be like, “I have this seven-minute song,” and he can go, “Sure.”

He’s done most of his work post-MTV as the hub of music videos. He’s been taking advantage of YouTube and file-sharing to do these more ambitious projects, in length at least.

It’s interesting to hear you talk about the importance of that pocket of work within the greater body, because I’m always fascinated in general by how we—as in the cultural we—rank a given filmmaker’s projects on a hierarchy. So when you google his filmography, there’s a very good chance that it’ll skip over things like Valentine and Anima and Junun (2015). But it feels like his music videos are less of a side project than with other filmmakers.

Yeah, I see the Joanna Newsom videos as a little bit like extensions of Inherent Vice (2014), certainly. The HAIM videos bleed directly into Licorice Pizza—that’s a whole movie that feels of a piece with those videos. And then there’s the Radiohead stuff, which feels like it exists a little on its own, I think.

And it’s through, I imagine, Jonny Greenwood that he starts working with Radiohead at all, and eventually he’s working just with Thom Yorke. He creates this big web, but the web is always staying pretty connected to the existing pieces.

Right, well he doesn’t usually… until he started working with HAIM, he didn’t make videos for people he didn’t already work with.

And of course, he’s now officially brought them into his feature universe. I thought the part in the music video chapter was interesting where you talk about how those collaborations with HAIM have given him a bit of… I don’t know what the right way of phrasing this is… cachet that he did not previously have with respect to women and their interiority? And the distinction you reference between the men in his work as beasts/fools and the women as angels/sages. Can you talk a little bit about that?

So it’s this idea that his movies are so dominated by the male voice, particularly up to the last three, where the female voice becomes a little more assertive in Inherent Vice, Phantom Thread (2017), and Licorice Pizza. But before that, his movies were about men talking, and talking and talking and talking and yelling and talking. And you see, then, the music videos as these offshoots where he is almost always working with women, with the exception of Michael Penn at the beginning of his career, and then his dalliances with the guys from Radiohead. He’s worked with Fiona Apple, Joanna Newsom, and the Haim sisters. And I think that’s it, just about.

And it’s interesting that he funnels all of his interest in female voices off into the music videos, for all intents and purposes. But he’s acting in the service of existing material; he’s not creating any new work for the voices of these women, he’s elevating their artistry. And so there’s this tension between the videos that are so female-focused and the features that are, up to a point, so male-focused. And as you say, he gets a little cachet from working with these cool young women, and it’s a little borrowed from them.

The same way that it was with Aimee Mann 20 years ago. Do you think that’s the first example of that?

I guess it is. The relationship with Aimee Mann is so interesting because it’s just that one movie [1999’s Magnolia]. And that movie, he said, was an adaptation of her songs.

And that’s fascinating to me for obvious reasons.

But because he didn’t do any music videos for her, except the one for Magnolia [1999’s “Save Me”], she falls off in my mind as one of his music collaborators.

This isn’t, like, important—it’s a bit of a diversion—but I was struck going through everything in such a short period of time by how the women in his work physically resemble each other across the decades. Not that that’s anything… necessarily… but Fiona Apple and Joanna Newsom and the Haim sisters’ faces all started to blur in my head. I would also maybe throw Katherine Waterston in there.

I was gonna say.

So there are Hitchcock Blondes, and there are Anderson Caramel Brunettes. At least as far as his onscreen women collaborators go, he has a type.

Totally.

Again, not that that’s anything. A more important thing that stuck out is that he’s always doing interesting things with movement. And I don’t mean choreography so much as the concepts and the staging, all the tracking shots. In many ways, he’s often making tracking videos, where we’re following someone around the city or down a hallway or, in the case of that one Radiohead video [2016’s “Daydreaming”], literally everywhere. What do you make of that, if anything?

I think it’s a really easy way to construct a video, just following a body through space. His videos are not often particularly high-concept.

No.

And so, if you can just come up with a space or a series of spaces to follow these musicians through, you can coast a lot on that. It’s a versatile setup. You’ve got the “Summer Girl” (2019) video with the Haim sisters taking off articles of clothing as they move through the L.A. street, to the Radiohead video where Thom Yorke is just stepping through environment after environment after environment. It’s versatile and durable.

And I think he is somebody who’s interested in the body in motion. A lot of his most iconic shots are… the roughnecks running towards the derrick fire in There Will Be Blood, or Freddie running across the cabbage fields in The Master—or motorcycling across the salt flats later on—or all of the running in Licorice Pizza. Movement is an expression of ecstasy or heightened emotion for him, most often, and comes at moments of great dramatic tension. So I think it makes sense that it comes up as a motif in the videos.

In terms of his music video collaborators, he does seem to gravitate towards artists who’re not particularly known for, like, artifice or theatrics. You write a bit about the spontaneity—or at least the spontaneous feel—of them, the things like natural light. And that might actually be a reason why I wasn’t already intimately familiar with the music video work. I think it’s a different corner of the pop sphere than I’m usually in. I feel like this is a good lead-in to talk about Jonathan Demme… may he rest in peace.

Yes.

Well, first of all, could you briefly explain how the two were acquainted?

So Jonathan Demme was an early favourite of PTA’s, and somewhere in the late ‘90s/early 2000s, they became acquainted. And I’m not totally sure how that relationship came about, but they were thick as thieves very quickly, and PTA helped Demme brainstorm a lot of the stuff for The Truth About Charlie (2002), his not-very-good but very interesting failed experiment of a Charade (1963) remake. And Demme was a mentor of PTA’s from then on, until he died around the time of Phantom Thread, and Phantom Thread is dedicated to him.

Demme is somebody who is known for, or is at least associated in a couple cases with, the idea of the gear-shift movie. That’s what PTA talks about loving with him, particularly Something Wild (1986). That’s a movie that—have you seen that one?

No, but I’ve edited work on it.

So that’s a movie where there’s a really distinct gear-shift. It goes from being sort of a frothy comedy to a violent thriller, really on a dime. And PTA has talked about that as a huge inspiration for him. He loves to borrow the “Demme close-up”—quote unquote—which is Demme’s signature shot of a character staring down the barrel of a lens.

Yep.

And he always talks about the Demme humanism. That’s the term most often associated with Demme.

You identify that as the big carry-over from Demme’s work to PTA’s.

PTA talks about how every character in a Demme movie feels like they have their own life, even if they’re just walking by in the background of a scene. He has this sort of effusive love for his characters and the worlds he creates.

It’s a vague thing to identify as your overriding influence, so it’s not as easy to point to that, I think, as it is to point to the ensembles of Altman carrying over, or the tracking shots of Scorsese carrying over. The Demme stuff is a little bit more holistic, in that it’s not always as flashy but there on an underlying level that unites the entire filmography.

I think the music video stuff underlined the connection for me between the two men a bit. I was reading this book the other day for a completely unrelated reason, this book of music video scholarship, and there was this quote that came up on the topic of New Order’s “The Perfect Kiss” (1985), which Demme directed, and it’s basically just the band performing the song. I’ll read you the quote if that’s not weird. Andrew Burke is the scholar writing this, and he writes:

Demme denies the viewer any kind of establishing shot that shows the band as a whole until nearly the halfway point of the track and that generates a sense of both trauma and tension.

I flagged that because you identify something similar as one of the other things that unites Demme’s work with PTA’s, and Lindsay [Zoladz] also writes about it in her foreword. Like, I think I’ll just let them perform the song, and we’ll go from there.

Yeah. “Simple for the cameras, complicated for the girls,” is what you hear him say in Valentine.

And that same approach is there in Demme’s Stop Making Sense (1984). It’s also there in something like “Night So Long” (2018), the video where we spend the entire first half just zoomed in on Danielle’s face. And there’s this sort of slow-burn—I won’t say torturous—effect at work. It’s anti-MTV, almost. Certainly not a traditional music video mode, though I think “Paper Bag” (2000) is an exception and there are a couple HAIM ones that are exceptions. Anima is maybe an exception, like Here’s Thom Yorke doing choreography—which I think is one of Anderson’s greatest gifts to society. Does that resonate at all?

The videos being anti-MTV?

Yeah. And obviously part of that is the timeline, because he sort of shows up at the tail end of the golden age of the network. But they’re also not designed to be pleasurable in the traditional music video sense.

It’s interesting, you left off a couple Fiona Apple ones that feel the most MTV-ish to me. I think the HAIM ones feel really distinct. More than that, the two videos he did with Jonny Greenwood and Thom Yorke—the Jonny, Thom, and a CR-78 drum machine.

And that’s the other thing, which is he’s not afraid to experiment with a bit of live stuff in music videos, which is not by any means the norm.

Those are two videos that feel almost anti-music video. They are so just “cameras trained on two performers highlighting the lack of artifice involved.” And then the same is true of Junun, which is sort of a feature-length music video, but also anti-every aesthetic quality of music videos.

I hadn’t seen that until this week, but it and Valentine are both in my research filmography now of films tied to studio albums. That’s for later, but I really enjoyed it.

I love that one because you get to see his mind working in real time. It’s just him and the camcorder—moving around, finding the shot, moving around, reorienting, finding the better shot.

For sure.

You never get to see a director working stream-of-consciousness like that.

I’m circling back a bit, but obviously on the topic of Fiona Apple, there was a bit of a wrench thrown in the public narrative of that relationship, which you acknowledge in your book. And this is probably a good time for me to say that I thought you struck a really great balance between “This artist means a lot to me” and “Here’s a weird thing they did once that I should probably acknowledge.” This is maybe a hard question, but I’m curious how much you have something like that in the back of your mind while you write. Are you already imagining your reader waiting for it to be mentioned, sort of scrutinizing the argument? I think the big reason I’m asking is that I do that, and I sometimes get tripped up on it, and I’m curious to hear any and all thoughts. You’re someone who I already know is good at taking something that you care about a lot but not writing about it in a way that’s… hagiographic, or a little too pedestal-y.

Well, I appreciate that. It’s hard not to get hagiographic, and my initial proposal was dinged by peer review for being too fan service-y.

Oh, interesting.

The responses from the peer reviewers of the proposals, one of them said, “Is this going to be a work of fan service?” And so I had to sharpen my critical lens a bit. And once you start doing that, it’s hard not to scratch the surface of everything. With PTA, I think there is a lot you can find once you scratch the surface of just your affection for the movies.

I was a little bit paranoid as I wrote about, like, frustrating [his] fans. If I’m talking about the sort of dodgy way he talked about race in the late-‘90s, or the even dodgier way he talked about race around Licorice Pizza, it was hard for me not to be writing with one ear over my shoulder for the frustrated fans… but simultaneously have the ear over my shoulder for the peer reviewers, who were gonna say, you know, “Has this had the sufficient analytical lens applied to it?”

I mentioned right off the top that writing a book was really hard and scary, and that was a big part of it, trying to write based on instinct while also having these competing pressures in the back of my mind.

The big balance is… not thinking of yourself or carrying yourself like a stan, while also knowing how to speak to one. How to communicate to one without losing them, so that they have no choice but to agree with what you’re saying, or at least understand where you’re coming from. What did you learn about yourself writing this book?

I think what I learned is not coming into play until now that I’m working on my second book, and what I have learned… is that writing a book does not teach you how to write another book. It seems like every book is going to be a challenge, figuring out how to tackle it all on its own, and you don’t just get to lean on having done it already.

Right.

And I learned that I could write a book, which physically is a very daunting task, just putting all of these words in order on the page. I feel good about the fact that I got that done.

How did you do it, on a week-by-week basis? Are you the get-up-at-five type?

At times—you have to be when you’ve got three little kids like I do. With the proposal, I had to put down a proposed word count and a proposed delivery date. And once you have those two things, I could break it down into the number of words I needed to have done every week, and then you create a little spreadsheet with the cells that magically do all the math for you—This week I wrote this many words, which is this much percentage of the chapter done, which is this much percentage of the book done. You see everything rearrange itself at the end of the week, and it’s very satisfying. And now I’m doing it again with this Bob Dylan book and discovering all over again, as I said, that it’s a huge challenge to put all these words in the right order.

So I’m allowed to ask you about this next book project? You’ll have to come back for another interview, by the way. Can you tell the crowd the gist of what you’re writing about?

I’m writing about Bob Dylan as a cinematic figure—Bob Dylan as the subject of documentaries, Bob Dylan as the director of a couple really bizarre experimental movies, Bob Dylan as the star of a couple movies of varying degrees of goodness, the subject of Martin Scorsese documentaries, the subject of Todd Haynes movies, and the mastermind of his own eventual Sundance movie. He has just been winding his way through Hollywood history since the ‘60s in a sort of low-key way where you may not have even noticed he was there. But you can’t tell the story of him without telling the story of all the movies he did, so that is what I’m doing: creating a sort of biography through film.

I’m very excited about it. I was wondering if that’s an easier book to loop your kids into in terms of the research process, but I don’t know if toddlers are necessarily interested in Bob Dylan.

They were more interested in HAIM; they loved those HAIM videos.

Right, and that’s kind of a rare sub-pocket of the PTA work that you can even show them, I imagine. Is that strange? Writing a book where you can’t do most of your screenings in the living room during daylight?

Well, something that I really enjoy doing is telling the stories of adult movies in kids’ terms. It’s a challenge that they love to throw at me and that I find really amusing. [Laughs] How much can you strip away all the adult content in a movie and still make it compelling to a kid? And my biggest challenge recently was trying to do this with the movie Air (2023). It is impossible to make that movie sound interesting to a child.

I’m picturing you right now doing a Doc Sportello bedtime story with your kids and trying to make it work, but it sounds like that’s what I’m meant to be picturing.

Exactly, yeah. It’s How much of the story can you maintain while not making it upsetting or offensive to them? And I have done it with all the Paul Thomas Anderson movies. There’s that great book, A Is For Auteur, that Cory Everett put out, and every page is a different director with a tableau of iconography from their movies splayed out behind them. And my kids love this book, and the first page is “A Is for Anderson.” You’ve got the derrick fire from There Will Be Blood, and the frogs falling from the sky, and the Dirk Diggler sign… I always try to skirt past Boogie Nights as quickly as possible. But they can point to the stuff and say, “Tell us about that movie,” and that is one of my favourite pastimes.

I have some rapid-fire questions, so feel free to answer them as briefly as I ask them. What is your favourite of the Jonny Greenwood scores?

Oh boy. I mean, hard to beat Phantom Thread.

It’s a great cooking album.

It’s a great everything album, a great writing album.

Do you have a favourite of PTA’s music-related stuff?

Some of the HAIM videos are such perfect little pops of pop. The “Little of Your Love” (2017) video, where it’s basically just a square dance or some kind of hoe down. It’s so low-concept but so ecstatic, so it’s hard to beat for me.

And I think you draw a line between that and the Boogie Nights club moments. What is your favourite music moment in a PTA project, and it doesn’t have to be a short-form one?

The “Jessie’s Girl” sequence, the Rahad Jackson/Alfred Molina sequence in Boogie Nights. It’s basically a little music video. That scene does not function the way it does without the juxtaposition of the pop music on the soundtrack.

Absolutely. Forgetting about the fact that they generally need to be tied into a feature project in order for this to happen, who is someone you’d like to see him work with from the music scene?

Boy… I would like to see him get back to work with Jon Brion. They have not worked together in many, many years. Not that I’d like to see anything go down between him and Jonny Greenwood, but I would love to see Jon Brion get back in the mix.

As for someone else, maybe I should just say Bob Dylan. Dylan did that great work [2021’s Shadow Kingdom] with Alma Har’el a year or two ago. They advertised that there was gonna be a Bob Dylan simulcast, so I bought a ticket thinking it would be a filmed performance. But it’s basically an hour-long music video with Bob Dylan doing smoky blues. So Paul, make one of those with Bob Dylan. Make my life easier and unite the two books. ●

Some odd(itie)s and ends...

- I really enjoyed Hilton Als’s New Yorker profile of Missy Elliott from 1997, where there’s quite a bit of focus on her videomaking

- The latest album I keep raving about is Amaarae’s Fountain Baby—go listen and let me know if it’s just me

- In case you missed it as a hyperlink in my Pride special from earlier this month, a new book that should be on your radar is Kyle Turner’s The Queer Film Guide

- I haven’t yet gotten around to The Idol (I did read an early draft of the first episode sometime last year, so it sort of feels like I have). But because I definitely find there to be a weird disconnect between pop stardom IRL and pop stardom onscreen—while you’re more or less required as a pop star these days to be a corporate powerhouse, you largely remain an at-risk puppet with no agency as far as the cultural imagination goes—I appreciated this Hazel Cills essay about exactly that

Mononym Mythology is a music video culture newsletter by me, Sydney Urbanek, where I write about mostly pop stars and their visual antics. I do that for free—and actually pay to use this platform—so if you happened to get something out of this instalment, you’re more than welcome to buy me a coffee. The best way to support my work otherwise is by sharing it. Here’s where you can say hello (if you received this in your inbox, you can also reply directly to it), here’s where you can subscribe, and I’m also on Twitter and Instagram.