A Moving-Image History of Parkwood Entertainment

If there’s one category of writing that I probably haven’t scrolled past in a decade, it’s anything related to Beyoncé’s filmography—not the films she’s starred in, but the many she’s made (though I’ll honestly read anything about the films she’s starred in, too).

My professional journey so far, put one way, has been from Beyoncé-loving undergrad student in film, to Beyoncé-researching grad student in film, to lapsed film scholar still paying a great deal of attention to Beyoncé. I started university in 2013, so that journey has nicely paralleled her own from beloved pop star to cultural behemoth known in large part for her visual releases. And as I said, I’ll read anything deconstructing that more famous journey on paper.

But maybe because I’ve read too much on the topic, there was a point at which I started to see some curious patterns in how it’s sometimes handled. And a couple of them eventually turned into what one might call respectful gripes.

For instance, we do this funny thing culturally where every new Beyoncé film is the one that should finally earn her cinephiles’ respect—and then the boulder seems to simply roll back to the bottom of the hill in time for her next release. Though a handful of writers had started attaching the word auteur to her work by the early 2010s, it was Lemonade (2016) that supposedly turned her into a “bonafide” one, Homecoming (2019) that led Netflix to tweet that her name was synonymous with the concept, and Black Is King (2020) that showed it was “time to start taking Beyoncé’s film-making seriously.”

The conversation has seemed tragically stuck there for much of the past decade—here’s why Beyoncé is a filmmaker you shouldn’t feel embarrassed to log on Letterboxd—in a way that’s hard to picture happening to anyone else. The sentiment obviously comes from a generous place, and mostly from admirers rather than detractors, but at what point do we deem it condescending for someone with directing credits on eight feature films? And how do we get unstuck?

Because even if we put their narrative content aside, Beyoncé’s films have given us a hell of a lot more to work with. They’ve drawn attention to our rigidness about genres—a funny little concept, aren’t they?—and how awards categories are designed to reflect that rigidness rather than challenge it. They’ve helped stoke investment in the visual album as a format, and have almost singlehandedly colloquialized that term. Their aesthetics are recognizable enough to be parodied in some corners of the industry, and yet are still widely and earnestly emulated in other corners. They also take home Grammys and Emmys and Peabodys, and regularly compete for awards up against work by less-questioned directors in the same space—to give a real mixed bag of a list here, people like Morgan Neville and Cameron Crowe, but also Spike Jonze and Paul Thomas Anderson.

The recent release of Renaissance: A Film by Beyoncé (2023) generated some truly excellent writing that suggested we were finally starting to be freed of our stuck-on-chapter-one curse. But funny enough, that helped make some space in my head for a few other respectful gripes to start crystallizing.

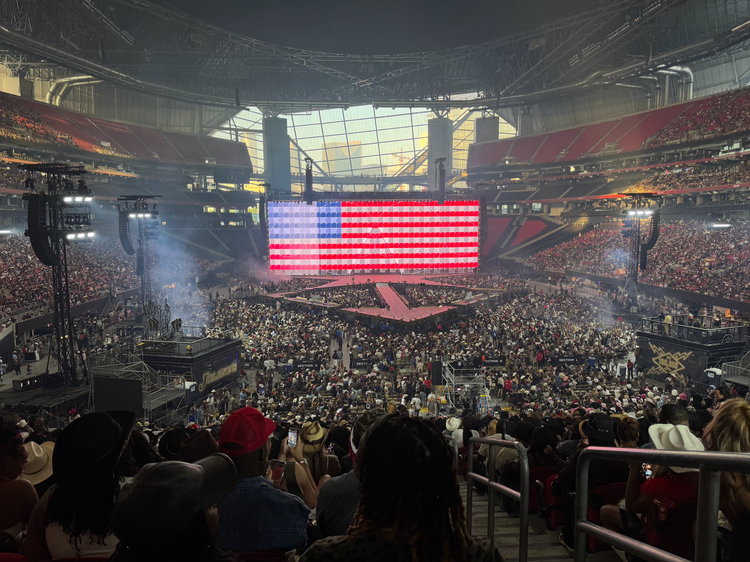

One was a basic framing thing: the Renaissance film is (at the time of writing) the latest entry in what’s now a two-decade body of connected work. It’s therefore in line with a style and approach and ethos pretty specific to Beyoncé’s film output—not to mention her ninth full-blown concert film just as a solo act. But because of the timing of its release in the fall of 2023, right around when Taylor Swift: The Eras Tour (2023) and the 4K restoration of Stop Making Sense (1984) were coming out, a lot of the conversation around Renaissance boiled down to “those concert films are so hot right now.” These specific three were made very differently and for very different reasons, and constantly mentioning them in the same breath had the effect of flattening them. And you’ll know if you’ve actually seen the material—I happily watched all three films in theatres with a cold beverage—how apples to oranges to bananas they are.

A related gripe is that writing about Beyoncé’s films only sometimes gets into the filmmaking proper, tending to talk more about what they symbolize—or what the star herself symbolizes in a given release context—than how something has actually been put together. To make a knowing generalization, we care less about the how of these films and more about the what of them; we routinely round up their cameos and couture pulls and Shadiest/Diva Moments, while formal details like editing and cinematography and sound design get altogether less airtime. All of these things can and even should have a place in film criticism and culture, we just lean very hard on one pillar at the expense of the other.

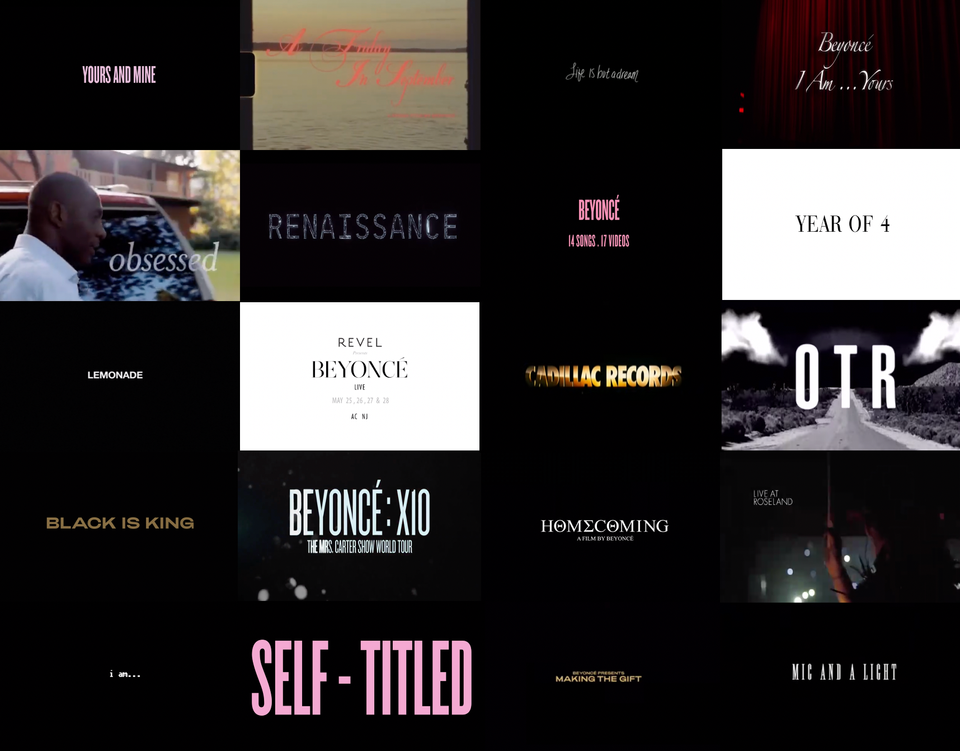

And here’s one final gripe for the road: when people do take a more macro look at Beyoncé’s directing career, they tend to pick and choose from it in a way that’s frustrating but illuminating as far as how we valorize different kinds of projects over others. We tend to exclude the pre-Lemonade features—three whole concert films and a traditional documentary—and we don’t usually include the many one-off music videos and short films, which have also played a key role on her journey. As a result, it isn’t common knowledge—even in the Beyhive!—that the star has directing credits on more than a dozen things before we start counting her three self-billed visual albums (and that’s just the projects where she’s bothered to include credits).

Is any of this Beyoncé’s fault? Sure—she’s never seemed interested in keeping a real list of this work anywhere, forcing people like me to make their own, and she’s largely closed herself off from participating in conversations about it. A not-insignificant slice of her weird treatment in the film space will also naturally come back to some combination of -isms.

But I’ve wondered if it’s worsened somewhat by the notion that she isn’t “really” directing the work on which she’s credited as a director, something I see suggested from time to time online. There’s little incentive to have a meaningful conversation about someone’s filmmaking if you don’t truly consider them a filmmaker, if you assume they’ve slapped a vanity credit on someone else’s work. After all, Beyoncé is different from the average musician-director in that she happily invites other directors along for the ride—enlisting a mix of established and up-and-coming talent for visual albums, and teaming up with longtime colleague Ed Burke for just about everything else.

It’s a method that makes sense for the stuff she embarks on: mixed-media tapestries woven together over months or years, whose genres are sometimes tricky to pin down, that often change in scope as they go (and don’t necessarily originate from a screenplay), where she’s also responsible for any A-game being brought in front of the camera. But as with Beyoncé’s tendency to make music collaboratively, she opens herself up to the charge that she “needs the help,” and it’s one that persists no matter how many eyewitnesses testify to her artistry or authorship, whether in the studio or on set.

No matter how you come down on this issue, though, Beyoncé’s visual output...

- bears a distinct style that’s been carefully developed over dozens of projects and, again, about two decades;

- brings with it a consistent list of thematic and narrative concerns, no matter the genre;

- often puts projects in direct conversation with each other, as if they’re asking to be considered on a more macro level;

- has been made by a relatively stable group of collaborators (including Burke, her directing partner of a decade and a half), to say nothing of the recurring onscreen characters;

- and is produced almost exclusively through Parkwood Entertainment, the company she originally founded in the late 2000s to get more into filmmaking.

You may be thinking, Lots of pop stars make movies, and that’s true—and basically the guiding principle of my professional life. That means I can say pretty confidently that Beyoncé’s presence in this space is unique a few different ways, bringing to the table a very specific mix of scale, achievement, and (for lack of a better word) gall that doesn’t really exist among her filmmaking musical peers. To put this trifecta in different words, she’s directed many films, they tend to be quite good, and they’re also Beyoncé-centric projects spearheaded by Beyoncé.

The star’s movies range from magnificent works of art to blatant PR exercises, and she’s even managed both at the same time. They’re one of the only channels through which she speaks to the public, and to line them all up is to see certain narratives unfold but also shift slightly as she gets older and wiser and bolder. They’re supplied in part by a “crazy archive” that she’s been nurturing since at least 2011, but they’re also a “crazy archive” all on their own. They’ve been an essential tool for her mythmaking as a public figure, at once where we’ve watched her live out her wildest dreams and battle her most stubborn demons.

And then there’s Parkwood, simultaneously the apparatus that’s made all of this possible and an actual focal point of many of these films. Okay, I may have lied when I said I was done with my gripes, but here’s my last one for real: people regularly write thousands of words about Beyoncé’s work—moving-image or not—without once acknowledging the LLC that assembles it piece by piece.

As I write this, Parkwood Entertainment is the company through which Beyoncé does everything: music, tours, clothing lines, charity work, investments, managing emerging acts, and more. Named after the street on which she lived for a time as a child—in a pretty house that she never settled in, one might say—fans often use “Parkwood” as shorthand for “Beyoncé acting in a professional capacity,” and we’ll probably come to say “Parkwood” the way we say “Graceland” or “Paisley Park.” Founding it is easily one of the most pivotal things Beyoncé has ever done for her career, the not-so-secret ingredient in why it now feels kind of silly to utter the words “Beyoncé Knowles.”

But the company’s earliest iteration was back in 2008 as Parkwood Pictures, a way for her to executive produce a couple of star vehicles and eventually co-direct her first feature. A decade and a half later, Beyoncé isn’t exactly the Oscar-winning screen legend she openly dreamed of becoming early in her career. And yet she’s still emerged as a key movie star of this century, not by wowing us with performances in other people’s films (though she has done that at least a few times) but by regularly releasing self-produced ones that better tap into her strengths as an artist and performer. They’ve become so much a part of her M.O. by this point that they’re now expected of her, and are sorely missed when they don’t materialize. (Release the visuals!)

But what does it actually mean that the home base of one of today’s biggest musicians has churned out far more films than albums?

As of today, I’ve officially been writing this newsletter for four years. And I generally like to celebrate its birthday by doing something special, whether that’s sending out an AMA (2021, 2022) or polling people I like with a music video question (2023). This year, in a poetic turn of events, I happened to mostly finish a long-gestating project that vibes rather nicely with the number four. And so you’re currently reading the introduction coming ahead of a four-part series that I’ll be sending out over the next however many months, called “A Moving-Image History of Parkwood Entertainment.”

A lot of this project is exactly what it sounds like: a longform fleshing out of the numbered list I made up above. But because I have issues with restraint, it’s also a walk-through of just about everything the four lady has done in the film space—from the early movies directed by other people, to the mid-career Thanksgiving specials for which she learned how to use Final Cut Pro, to the more recent big spectacles that have her name somewhere in the title. Through all of that, we’ll talk about one of the things that got me hooked on Beyoncé in the first place: how she’s engaged with film history and culture at just about every turn in her career—in her music videos and films, but also in her lyrics, ads, live performances, and photoshoots.

The first chapter of this series is, ridiculously, about all the years of Beyoncé’s life that led up to Parkwood, 1981 through 2007, when she did everything she could to set herself up for big-screen success. The second one dives into the transitional years that were 2008 to 2012, when she may have realized that she’d been approaching movie stardom wrong, looking for roles of a lifetime when there was greater opportunity in interrogating and perfecting her own narrative. In the third chapter, on 2013 through 2017, our leading lady cements herself as a visual innovator through a number of acclaimed self-directed projects. And in the final one, she arrives at a go-to subtitle—“A Film by Beyoncé”—that brands her approach as uniquely her own.

This is a project that I spent years desperately wishing I could read before I started chipping away at it myself, and it was partly an excuse to go back through everything Beyoncé has done onscreen. I set out primarily to make some connections for myself as a fan/scholar, but I’d also love to have more interesting conversations about her films going forward, and delusionally have been wondering if I can help move that needle even an inch.

With that in mind, I’ll be trying to create a definitive-as-possible list of Beyoncé’s film output, bolding titles as I first mention them and then collecting those at the end of each chapter. (The final one collects the titles from all four pieces.) Once I’m officially on the other side of this series, the list will always be there for me—and you—to come back to; there are plenty of projects that I’ve had to give a mere surface-scratch, but that I’ll surely want to revisit later, after I’ve given my household a few weeks Beyoncé-free.

I’d say that I’ve written this whole thing in bits over the past couple of years, but some of it’s been in my head for longer; certain thoughts have appeared in various academic papers and freelance pieces, and realistically in the odd tweet, too. But I’d like to think that they’re neither overly academic nor stanny, and I hope I can bring something new to this story no matter your familiarity with it. Moving through each chapter, I’ve done my best to cover these films and their content/context as responsibly and sensitively as possible, but I’ll drop a general note here anyway and say that there’ll be discussion throughout of things like dieting, pregnancy loss, and police brutality.

My overwhelming wish is that you treat this like a guided tour through Beyoncé’s filmmaking journey, but one that was written specifically by me—both shaped and limited by my own interests and expertise and lived experience. I hyperlink out to other writers anytime I’m feeling a bit more useless, and I generally hyperlink out to other sources all the time; to clarify what I said earlier, there’s lots of wonderful work out there on Beyoncé and her films, and one sub-goal of this project was to cite as much of it as I could.

I’m self-publishing all of this on the internet for free because I’m clearly—as the star herself once sang—gone in the brain, and trust me that I agonized over that decision. Ultimately, I want anyone to be able to find and read it, I want to include lots of stills, and there’s of course a learned desire for editorial control. In some ways, I guess I was inspired by my subject here: to take a leap in the name of a project I care about and exploit myself only on my own terms. Besides, there are greater hardships than going back through the work of one of your favourite artists, and I learned so much doing this that my brain tripled in size. I’ll be fine.

All of that said, if this strikes you as a compelling read and/or you’d like to receive each chapter a little before everyone else, please feel free to subscribe to this newsletter, where you can expect regular (but not too regular!) issues going forward, especially with this project no longer sitting on my shoulders. (I have a brand new About page where you can learn more about this newsletter and me, and also a brand new Other Work page.)

Just as lovely would be forwarding this email or link to even a single person whom you think might enjoy a series about Beyoncé’s evolution as a film star and filmmaker.

But anyway, wish me luck, and I’ll be in touch soon to talk Foxxy Cleopatra, Bob Fosse, Beyoncé’s first real visual album, and a whole lot more. ●

You can read the first chapter here.

Mononym Mythology is a newsletter by me, Sydney Urbanek, where I write about various intersections of popular music and moving images. You can reply directly to this issue if you received it in your inbox, and otherwise my email is here. I’m also on X and Instagram.